Dr. Amil Sharma and colleagues look into the applications of triple antibiotic paste for endodontics.

Drs. Amil Sharma, Stephen Cohen, Greeshma Gupta, Gregori M. Kurtzman, and Vivek Kumar Pathak discuss the applications of triple antibiotic paste (TAP) to endodontics

Abstract

This study investigated the latest findings and notions regarding triple antibiotic paste (TAP) and its applications in dentistry, particularly endodontics. TAP is a combination of three antibiotics — ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline. Despite the problems and pitfalls research pertaining to this paste has unveiled, it has been vastly used in endodontic treatments. The paste’s applications vary, from vital pulp therapy to the recently introduced regeneration and revascularization protocol. Studies have shown that the paste can eliminate root canal microorganisms and prepare an appropriate matrix for further treatments. This combination is able to remove diverse groups of obligate and facultative gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, providing an environment for healing. In regeneration protocol cases, this allows the development, disinfection, and possible sterilization of the root canal system, so that new tissue can infiltrate and grow into the radicular area. TAP has diverse uses as an antibacterial intracanal medication. Nevertheless, despite its positive effects, the paste has shown drawbacks. Further research concerning the combined paste and other intracanal medications to control microbiota is imperative.

Introduction

There is no greater association between the basic science and the practice of endodontics than that of microbiology. One of the strongest factors contributing to the controversies often encountered in the endodontic field is the lack of understanding that the disease processes of the pulp and periradicular tissues generally have a microbiological etiology. The vast majority of diseases of dental pulp and peri radicular tissues are associated with microorganisms. After the microbial invasion of these tissues, the host responds with both nonspecific inflammatory responses and with specific immunologic responses to encounter such infections. Pulp diseases are the main cause of the invasion of endodontic spaces by oral microbial flora. The survival of bacteria and fungi in this environment depends on a series of factors that involve the presence of nutrients, the environmental conditions of anaerobiosis, the pH value, competition/cooperation with other microorganisms, and the microenvironmental characteristics. The environment determines which microorganisms survive, and some can survive under unfavorable conditions.

The very first aim of endodontic treatments is to eliminate as many bacteria as possible from the root canal system and create an environment in which no remaining microorganisms can survive.15 Ideally, this can only be obtained through the use of a combination of aseptic treatment techniques, chemo-mechanical preparation of the root canal, antimicrobial irrigation, and intracanal medicaments.15,16 Approximately 50% of root canal peripherals and ramifications may remain uninstrumented during preparation of the root canal.17 In this condition, the remaining necrotic tissues may act as a nutrition source for the surviving bacteria.18,19 Thorough and systemic mechanical instrumentation, irrigation, and use of inter-appointment medication can perhaps reduce this phenomenon. Medicaments can play an important role in the preparation of the root canal for further therapies;17 for example, in necrotic pulps and active exudation.20 Calcium hydroxide has long been used as an inseparable part of root canal treatment in necrotic cases, resulting in less signs and symptoms. Traditionally, calcium hydroxide has been used in open-apex teeth with necrotic pulp tissues for inducing a bridge and preparing the root canal space for forthcoming therapies. Without the use of inter-appointment intracanal medications, such successful results are far-fetched.20,21

The type of intracanal medication depends upon the precise diagnosis of the tooth condition, a thorough knowledge of the type of microorganisms involved, and finally, their mechanisms of growth and survival. The presence of bacteria within the root canal is the main factor of endodontic disease, and therefore, the use of an antimicrobial agent is essential. Many forms of intracanal medicaments, apart from antibiotics and calcium hydroxide, have been used in an attempt to accomplish the above aim.22 These mainly include chlorhexidine and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.23

Currently, the common antibiotic-containing commercial pastes are Ledermix® (Lederle Pharmaceuticals, Wolfratshause, Germany) and Septomixine Forte (Septodont, Saint-Maur, France).24,25 Both preparations have corticosteroids as anti-inflammatory agents. However, neither of these pastes can be considered suitable for use against endodontic microbiota owing to their inappropriate spectrum of activity.17,23 Several studies have investigated different root canal antibiotic agents.26

Recently, another combination of antibiotics, called triple antibiotic paste (TAP) was introduced especially for the regeneration and revascularization protocol and the treatment of open apex teeth with necrotic pulp. This material has also shown other applications in endodontics.25 Initially, TAP was largely developed by Hoshino and colleagues,24 who investigated the effectiveness of the paste on the removal of microorganisms from the root canals.27 Researchers have also used TAP in vitro to disinfect Escherichia coli-infected dentin.27 Later, particular attention was given to the antibiotic paste and its effect against microorganisms present in carious dentin and infected pulp. The outcome showed excellent results in the eradication of the bacteria from the radicular system.28

TAP is a combination of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline.29 Metronidazole, as a nitroimidazole compound, is particularly toxic to anaerobes and is considered an antimicrobial agent against protozoa and anaerobic bacteria. Minocycline is bacteriostatic and shows activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It also causes an increase in the amount of interleukin-10, which is an inflammatory cytokine. Moreover, ciprofloxacin — as a synthetic fluoroquinolone — possesses fast bactericidal action and exhibits high antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria, and with limited activity against gram-positive ones. Many anaerobic bacteria are resistant to ciprofloxacin. Hence, it is often used with metronidazole in treating mixed infections to compensate for its limited scope.30 Therefore, TAP can affect gram-negative, gram-positive, and anaerobic bacteria, and this combination can be effective against odontogenic microorganisms.31

If the TAP is to be used, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline should be mixed equally (1:1:1)2,25,32 to a final concentration of 0.1–1.0 mg/mL.33,34

Applications of TAP in endodontics

The applications of TAP in endodontics can be considered as follows:

- In the regeneration and revascularization protocol of the pulp

- As an intracanal medicament for the treatment of:

- Periapical lesions

- External inflammatory root resorption

- Root fracture

- Primary teeth

- As an intracanal agent to control flare-ups

- As a medicated sealer (to prevent possible re-infection)

- As an addition to gutta-percha points in root canal obturation (known as medicated gutta-percha points)

- As an intracanal medicament loaded on a scaffold

Materials and methods

Case 1

A 19-year-old female patient reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, IDEAS Dental College, Gwalior, India, with a chief complaint of pain in the upper front teeth. She gave a history of mild intermittent pain in the region of the upper front teeth. Her further history revealed that the patient had a blow to her front teeth when she was 10 years old. No treatment was performed after that.

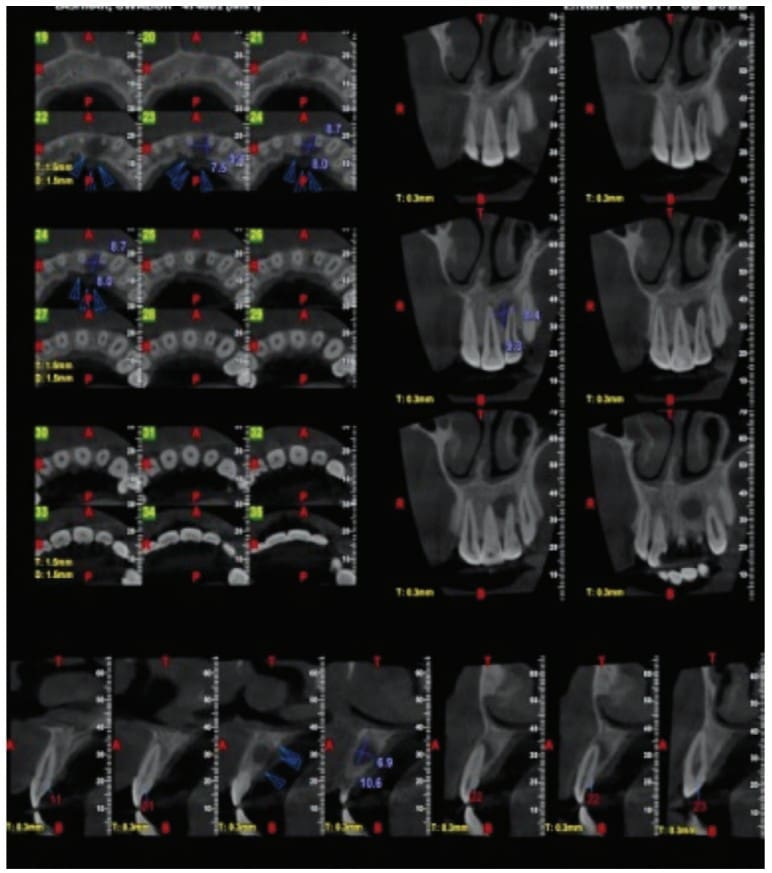

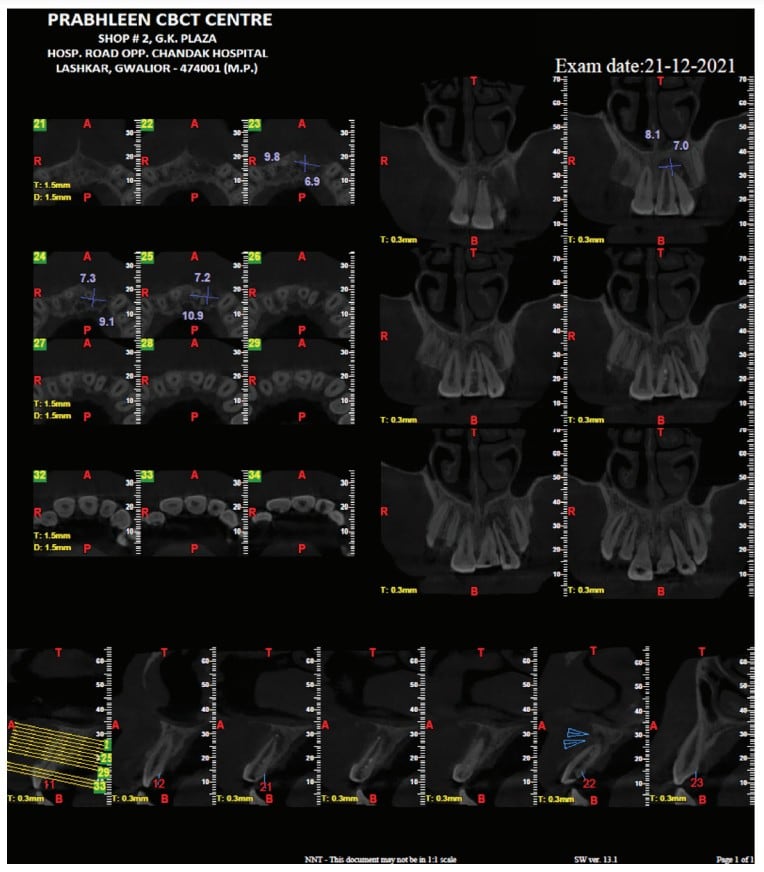

On intraoral examination, it was seen that the patient had mild discomfort on vertical percussion with respect to her upper maxillary left central and lateral incisors. The patient also complained of discomfort while palpating the mucobuccal fold corresponding to these incisors. An intraoral periapical radiograph showed the presence of large periapical radiolucency with irregular outline corresponding to upper maxillary left central and lateral incisors. Pulp sensibility tests (thermal and electric pulp tests) were then performed to determine the teeth responsible. As per the tests, it was concluded that only the maxillary central left and lateral incisors were the culprit.

The patient was reluctant for any sort of surgical procedure as she described an intense fear of any surgical intervention. Therefore, a non-surgical approach was chosen to treat this case of asymptomatic apical periodontitis associated with necrotic pulp. Access opening was carried out under proper aseptic conditions for both the upper central incisors. The working length was determined, and canals were shaped with K-files (Dentsply-Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) to an apical preparation of ISO size No. 80. During the preparation, the canals were irrigated with 2.5% NaOCl (Novo Dental Products Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India), 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (B.N. Laboratories, Mangalore, India), and 0.2% chlorhexidine (Vishal DentocarePvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, India) with in between saline flush to remove the necrotic debris from the pulp space. The access cavity was sealed with zinc-oxide-eugenol temporary restoration (Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India). The next day, the patient returned with severe pain with respect to both teeth. On examination, it was seen that both the maxillary central left and lateral incisors were severely tender to percussion. It was concluded that it was a case of mid-treatment flare-up. The canals were opened again. Pus discharge was allowed to drain. Canals were dried, followed by closed dressing. The patient was put on systemic antibiotics (Amoxicillin; Amox 500 mg 3 times daily 5 days) and analgesics (Ibuprofen; Brufen 400 mg twice daily for 3 days).

On the recall visit after 4 days, it was seen that the patient still had mild tenderness and that the canals were still weeping on the removal of the temporary restoration. The canals were once again irrigated with chlorhexidine, and an intracanal medicament, TAP, was placed. The TAP was prepared as described by Takushige, et al.,9 using commercially available tablets of ciprofloxacin (Cifran 500 mg, Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd., India), metronidazole (Metrogyl 400 mg, J.B. Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Ltd., India) and minocycline (Minoz 50 mg, Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd., India). Following the removal of the enteric coating of the tablets, the contents were pulverized using a mortar and pestle and mixed with propylene glycol to obtain a paste form. The paste was packed into the canal using a hand plugger, and the access was sealed with zinc-oxide-eugenol temporary restoration (Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India). The patient was then recalled after 2 weeks, and the canals were then free of any exudate. The TAP was again placed as an intracanal medicament. On her next visit after 2 weeks, a slight greenish tinge was noticed in the upper central incisors, which was not very significant.

Since both the teeth were asymptomatic, antibiotic paste was removed, and the canals were obturated with gutta percha (Dentsply-Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and AH Plus® sealer (Dentsply, De Trey, Konstanz, Germany) using the lateral compaction technique. An interim glass ionomer restoration was then placed. The patient was asked to get the core build up and full coverage crowns from the place where she was going to continue her further studies. As she could not find time, she came back to the institution for the completion of the treatment during her vacation. On examination, the teeth were asymptomatic, and post-obturation radiograph taken after 18 months showed an increase in periradicular bone density suggestive of progressive healing.

Case report 2

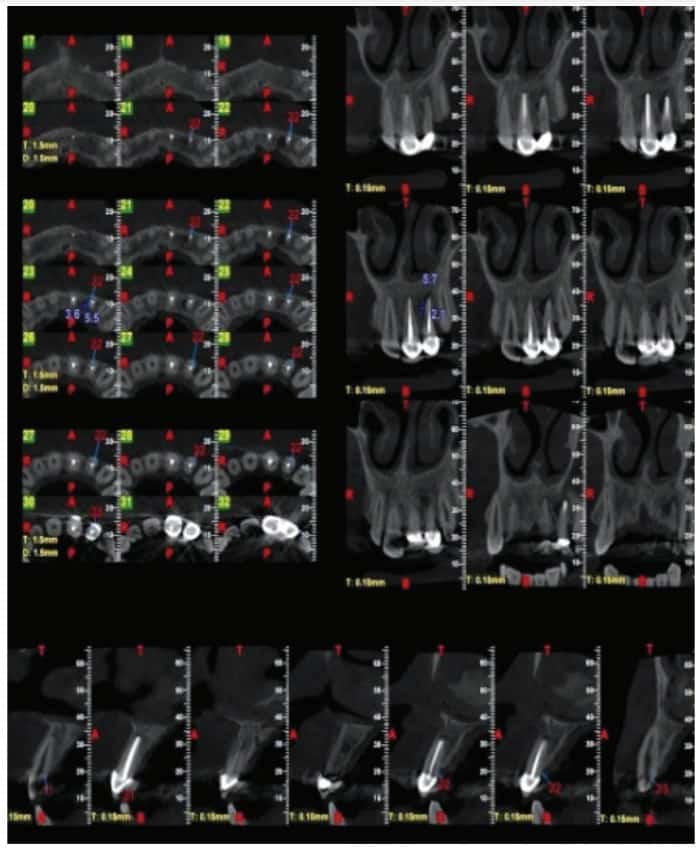

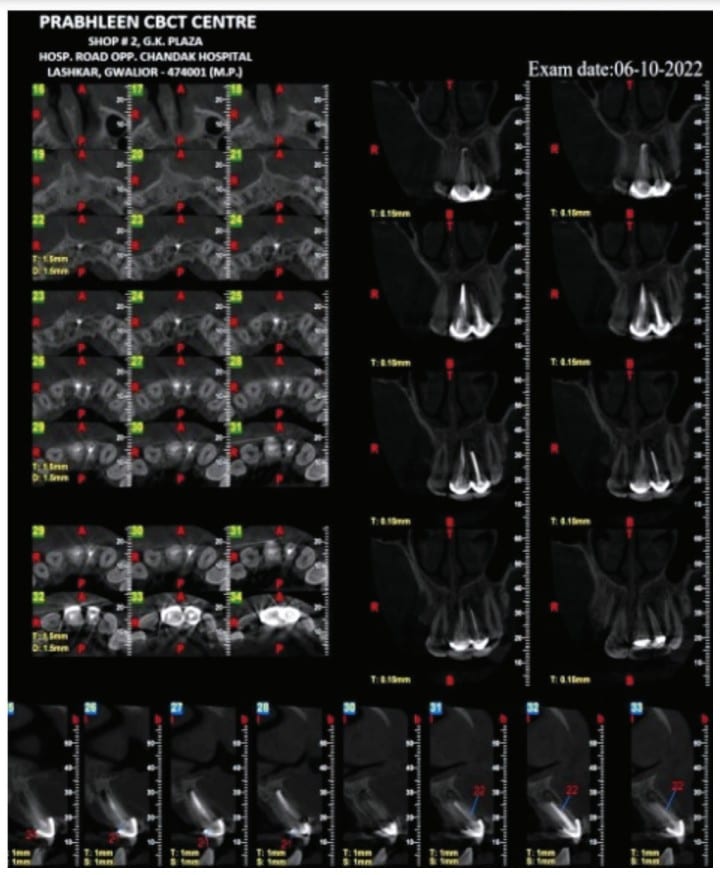

A 19-year-old male reported to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics at the Institute of Dental Education and Advance Studies (IDEAS), Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India, with a complaint of pain in her upper left front region with medical history status of trauma 5 years prior. Two months earlier, he noticed the formation of the sinus tract in relation to her central incisor with purulent discharge. An intraoral examination revealed that the RCT was already attempted, which did not relieve patient’s issues. An extraction was advised, but the patient was not willing to undergo an extraction. There was presence of a sinus tract and inflamed gingiva in relation to the tooth. The electronic pulp test was negative. An intraoral periapical radiograph showed periapical radiolucency so a CBCT was recommended. At the same appointment, the root canal treatment was initiated on her central and lateral incisor. An access cavity opening was done, and hemorrhagic, purulent exudate was found. The working length was estimated using electronic apex locator (RAYPEX® 6 VDW Inc.; Munich, Germany). Biomechanical preparation was done with K-file 10–40 using a step-back technique. During the instrumentation, the canal was irrigated copiously with 3% sodium hypochlorite solution using a 27-gauge endodontic needle after each instrument. Drainage was performed until the discharge through the canal ceased. The canals were irrigated, and the smear layer was removed with 17% EDTA followed by 3% sodium hypochlorite. The canals were dried, and a triple antibiotic paste consisting of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline (100 mg of each drug in 0.5 ml total volume) was placed with the help of a lentulo spiral. The dressing was changed after every month for 3 months until the teeth showed no symptoms. On intraoral examination, the teeth showed complete resolution of sinus as soft tissues were found healthy, and the canals were dry. Final irrigation was done with 2% chlorhexidine, and canals were obturated with gutta percha using a lateral compaction technique. The restoration was accomplished with composite.

Discussion

A “Comparison between the Antimicrobial Effects of Triple Antibiotic Paste and Calcium Hydroxide Against Enterococcus Faecalis” suggested that the triple antibiotic paste with either 2% chlorhexidine or normal saline would be the preferred medicament against E. faecalis and, among its three components, minocycline has the greatest antibacterial effect.1

Comparative analysis of tooth discoloration induced by conventional and modified triple antibiotic pastes used in regenerative endodontics was carried out, and it was inferred that modified TAP with clindamycin did not induce clinically visible discoloration up to 3 weeks after placement. In this, minocycline or doxycycline were replaced by clindamycin. However, further in-vivo research is needed.2

Regarding the discoloration caused by TAP, which is composed of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and minocycline, Kim, et al.,14 showed that minocycline was the main cause of tooth discoloration due to TAP. Thus, it has been suggested to use other antibiotics such as cefaclor,23,24 fosfomycin,24 amoxicillin,13,20,24 or Augmentin12 instead of minocycline or DAP (ciprofloxacin and metronidazole)25 instead of the classic TAP.21 In another study, Kahler, et al.,13 indicated that despite replacement of minocycline with amoxicillin, 10 out of 16 teeth that underwent regenerative treatment showed coronal discoloration. Also, replacement of minocycline with cefaclor and doxycycline in another study did not prevent visible coronal discoloration of teeth following application of these drugs for three weeks.25 Thus, strategies to prevent coronal discoloration following the use of antibiotic compounds must be studied in further detail. However, TAP is one of the most commonly used intracanal medicaments for disinfection in regenerative endodontic procedures and is one of the suggested medications in the American Association of Endodontists guidelines. Considering the risk of coronal discoloration following the use of TAP, future studies are required to assess the antibacterial effects of lower concentrations of TAP on the biofilm. Lower concentrations of TAP have easier clinical application and better penetration into the root canal system, although they can be washed from the root canal system and need a scaffold. Also, production of nano-TAP can be an interesting topic for future research. It should be noted that considering the critical role of stem cells in endodontic regenerative treatments and the coronal discoloration potential of TAP, future studies are required to find a medicament with the least side effects for this treatment protocol.

TAP was used as the medicament of choice for the non-surgical endodontic therapy in the present case as previous studies have shown its effectiveness in the elimination of the microorganism from the root canal system.6,9,11 Hoshino, et al.,11 in their in-vitro study on the antibacterial efficacy of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and minocycline alone and in combination against the bacteria of infected dentin, infected pulps and periapical lesions showed that they are incapable of complete elimination of bacteria, when used alone. However, in combination, these drugs were able to consistently sterilize all samples. Hence the concept of lesion sterilization and tissue-repair therapy; i.e., the combination of the above-mentioned drugs can be employed in infected teeth with large periapical lesions where diverse microflora can be encountered. In accordance with the previous study, the present case reports also demonstrated favorable healing of the large periapical lesion with non-surgical endodontic therapy using TAP.7,12

Calcium hydroxide, which is the commonly used intracanal medicament, has shown limited effectiveness in disinfecting the root canal system because of the dentinal protein buffering and its inability to eliminate certain microorganism especially within biofilms.5 Long-term calcium hydroxide placement has shown to result in higher incidence of root fracture either due to the disruption of the link between the hydroxyapatite crystals and the collagenous network in dentin or because of the reduced organic support due to denaturation and hydrolysis.13 Hence, the use of TAP can overcome these disadvantages of calcium hydroxide. TAP is also biocompatible as evident from its use in regenerative endodontics.14

Petrino, et al., (2010), while applying revascularization protocol using a triple antibiotic paste and a coronal seal of mineral trioxide aggregate on six immature teeth with apical periodontitis discovered that all six teeth showed resolution of periapical radiolucencies, and three showed root development.

Several studies have shown the effect of TAP in controlling endodontic flare-ups34 in diabetic patients between treatment appointments. Interestingly, TAP has shown to be more effective than calcium hydroxide in these patients.35 The combination of the three existing antibiotics seems to be able to defeat bacterial resistance and subsequently result in increased antimicrobial action.36 The anti-inflammatory ability of minocycline can synergistically assist in treating the disease.

Conclusion

If endodontics is to succeed, root canal microbiota should be properly reduced. Endodontic treatments rely mainly upon the elimination and possible eradication of the involved microbiota and their various virulent features from the root canal system. Biomechanical instrumentation, though an essential step, does not always provide such an environment in the root canal system. Non-instrumentation methods such as tooth repair and strategies towards maintaining a situation for regeneration and revascularization of the pulp should be considered, in which local use of drugs, particularly antibiotics, has shown their significance. Among the combination of antibiotics, TAP, owing to its effectiveness on different microorganisms and its diverse applications and triumphs, is of particular interest in endodontics. However, development of resistant bacterial strains and tooth discoloration are some of its pitfalls. Nonetheless, TAP seems to be a successful combination of drugs in root canal disinfection, possible coronal canal sterilization, and pulp regeneration and revascularization protocol. All currently available antimicrobial materials for radicular irrigation and medication have their own benefits and limitations; the search for creating the ideal irrigant and inter-appointment medicament continues.

The use of an antibiotic in endodontics requires some caution. Dr. Eoin Mullane examines use and abuse of antibiotics in endodontics in this article. https://endopracticeus.com/ce-articles/use-and-abuse-of-antibiotics-in-endodontics/

- Adl A, Shojaee NS, Motamedifar M. A Comparison between the Antimicrobial Effects of Triple Antibiotic Paste and Calcium Hydroxide Against Entrococcus Faecalis. Iran Endod J. 2012 Summer;7(3):149-55. Epub 2012 Aug 1.

- Venkataraman M, Singhal S, Tikku AP, Chandra A. Comparative analysis of tooth discoloration induced by conventional and modified triple antibiotic pastes used in regenerative endodontics. Indian J Dent Res. 2019 Nov-Dec;30(6):933-936.

- Nosrat A, Li KL, Vir K, Hicks ML, Fouad AF. Is pulp regeneration necessary for root maturation? J Endod. 2013 Oct;39(10):1291-5. Epub 2013 Aug 27.

- Kahler B, Mistry S, Moule A, Ringsmuth AK, Case P, Thomson A, Holcombe T. Revascularization outcomes: a prospective analysis of 16 consecutive cases. J Endod. 2014 Mar;40(3):333-8. Epub 2013 Dec 15. Erratum in: J Endod. 2014 Jun;40(6):879.

- Kim JH, Kim Y, Shin SJ, Park JW, Jung IY. Tooth discoloration of immature permanent incisor associated with triple antibiotic therapy: a case report. J Endod. 2010 Jun;36(6):1086-91.

- Thomson A, Kahler B. Regenerative endodontics–biologically-based treatment for immature permanent teeth: a case report and review of the literature. Aust Dent J. 2010 Dec;55(4):446-52.

- Saber Sel-D, El-Hady SA. Development of an intracanal mature Enterococcus faecalis biofilm and its susceptibility to some antimicrobial intracanal medications; an in vitro study. Eur J Dent. 2012 Jan;6(1):43-50.

- Thibodeau B, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dent. 2007 Jan-Feb;29(1):47-50.

- Sato T, Hoshino E, Uematsu H, Noda T. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility to combinations of drugs on bacteria from carious and endodontic lesions of human deciduous teeth. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993 Jun;8(3):172-176.

- Athanassiadis B, Abbott PV, Walsh LJ. The use of calcium hydroxide, antibiotics and biocides as antimicrobial medicaments in endodontics. Aust Dent J. 2007 Mar;52(1 Suppl):S64-82.

- Sato I, Ando-Kurihara N, Kota K, Iwaku M, Hoshino E. Sterilization of infected root-canal dentine by topical application of a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline in situ. Int Endod J. 1996 Mar;29(2):118-24.

- Ozan U, Er K. Endodontic treatment of a large cyst-like periradicular lesion using a combination of antibiotic drugs: a case report. J Endod. 2005 Dec;31(12):898-900.

- Takushige T, Cruz EV, Asgor Moral A, Hoshino E. Endodontic treatment of primary teeth using a combination of antibacterial drugs. Int Endod J. 2004 Feb;37(2):132-8.

- Hoshino E, Kurihara-Ando N, Sato I, Uematsu H, Sato M, Kota K, Iwaku M. In-vitro antibacterial susceptibility of bacteria taken from infected root dentine to a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline. Int Endod J. 1996 Mar;29(2):125-30.

- Taneja S, Kumari M, Parkash H. Nonsurgical healing of large periradicular lesions using a triple antibiotic paste: A case series. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010 Jan;1(1):31-5.

- Rosenberg B, Murray PE, Namerow K. The effect of calcium hydroxide root filling on dentin fracture strength. Dent Traumatol. 2007 Feb;23(1):26-9.

- Huang GT. A paradigm shift in endodontic management of immature teeth: conservation of stem cells for regeneration. J Dent. 2008 Jun;36(6):379-86.

- Mohammadi Z, Abbott PV. On the local applications of antibiotics and antibiotic-based agents in endodontics and dental traumatology. Int Endod J. 2009 Jul;42(7):555-67.

- Madhavan S, Muralidharan. Comparing the antibacterial efficacy of intracanal medicaments in combination with clove oil against Enterococcus faecalis. Asian J Pharm Clin Res.2015;8(5):136–138.

- Murvindran V, Raj JD. Antibiotics as an intracanal medicament in endodontics. J Pharm Sci Res.2014;6(9):297–301.

- Love RM. Enterococcus faecalis–a mechanism for its role in endodontic failure. Int Endod J. 2001 Jul;34(5):399-405.

- Peters OA. Current challenges and concepts in the preparation of root canal systems: a review. J Endod. 2004 Aug;30(8):559-567.

- Park HB, Lee BN, Hwang YC, Hwang IN, Oh WM, Chang HS. Treatment of non-vital immature teeth with amoxicillin-containing triple antibiotic paste resulting in apexification. Restor Dent Endod. 2015 Nov;40(4):322-327. Epub 2015 Aug

- Huang GT. Apexification: the beginning of its end. Int Endod J. 2009 Oct;42(10):855-866.

- Longman LP, Preston AJ, Martin MV, Wilson NH. Endodontics in the adult patient: the role of antibiotics. J Dent. 2000 Nov;28(8):539-548.

- Chu FC, Leung WK, Tsang PC, Chow TW, Samaranayake LP. Identification of cultivable microorganisms from root canals with apical periodontitis following two-visit endodontic treatment with antibiotics/steroid or calcium hydroxide dressings. J Endod. 2006 Jan;32(1):17-23.

- Hoshino E, Kurihara-Ando N, Sato I, Uematsu H, Sato M, Kota K, Iwaku M. In-vitro antibacterial susceptibility of bacteria taken from infected root dentine to a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline. Int Endod J. 1996 Mar;29(2):125-130. 28.

- Banchs F, Trope M. Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol? J Endod. 2004 Apr;30(4):196-200.

- Asgary S, Kamrani FA. Antibacterial effects of five different root canal sealing materials. J Oral Sci. 2008 Dec;50(4):469-474.

- Sato I, Ando-Kurihara N, Kota K, Iwaku M, Hoshino E. Sterilization of infected root-canal dentine by topical application of a mixture of ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and minocycline in situ. Int Endod J. 1996 Mar;29(2):118-124.

- Thibodeau B, Teixeira F, Yamauchi M, Caplan DJ, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2007 Jun;33(6):680-689.

- Hargreaves KM, Giesler T, Henry M, Wang Y. Regeneration potential of the young permanent tooth: what does the future hold? J Endod. 2008 Jul;34(7 Suppl):S51-56.

- Diwan A, Bhagavaldas MC, Bagga V, Shetty A. Multidisciplinary Approach in Management of a Large Cystic Lesion in Anterior Maxilla – A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 May;9(5):ZD41-43. Epub 2015 May 1.

- Bose R, Nummikoski P, Hargreaves K. A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. J Endod. 2009 Oct;35(10):1343-1349.

- Yassen GH, Chu TM, Gallant MA, Allen MR, Vail MM, Murray PE, Platt JA. A novel approach to evaluate the effect of medicaments used in endodontic regeneration on root canal surface indentation. Clin Oral Investig. 2014 Jul;18(6):1569-1575

- American Association of Endodontists. AAE clinical considerations for a regenerative procedure. Revised 6-8-16. Chicago (IL): American Association of Endodontists; 2016. https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/06/currentregenerativeendodonticconsiderations.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2023.

- Parasuraman VR, Muljibhai BS. 3Mix- MP in Endodontics – An overview. IOSR J Dent Med Sci.2012;3(1):36–45.

- Asgary S, Ahmadyar M. Vital pulp therapy using calcium-enriched mixture: An evidence-based review. J Conserv Dent. 2013 Mar;16(2):92-98.

- Thakur L, Goel M, Sachdeva GS, Katoch K, Pradad R. Regenerative endodontics: a comprehensive review. EC Dent Sci.2016;3:556–567.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..