CE Expiration Date:

CEU (Continuing Education Unit): Credit(s)

AGD Code:

Educational aims and objectives

This clinical article aims to discuss the immediate and long-term management of a 10-year-old with an avulsed upper central incisor.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify the protocols for the immediate and long-term management of an avulsed tooth sing support from the literature.

- Determine pulp and periodontal ligament (PDL) factors that affect the prognosis of the avulsed tooth.

- Identify some storage options to facilitate root resorption and pulpal healing.

- Recognize the effect of apical maturity on the avulsed tooth.

- View some guidelines from various sources for the management of avulsed teeth.

Dr. Meera Patel discusses the immediate and long-term management of an avulsed upper central incisor

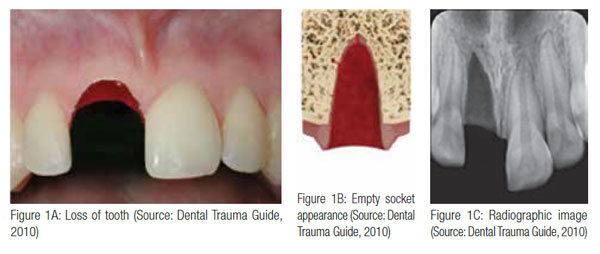

Avulsion is defined as the complete displacement of a tooth from its socket in alveolar bone owing to trauma (Andreasen, et al., 2003) and is one of the most serious of all dental injuries. Avulsion of a permanent tooth is estimated to represent 0.5% to 16% of all dental injuries (Andreasen, Andreasen, Andersson, 2007). It occurs most frequently between the ages of 7 to 14 years, affecting the maxillary central incisors (Trope, 2011).

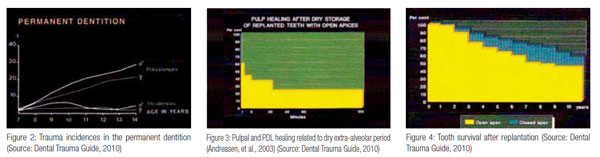

Andreasen, et al. (2003), found that in the permanent dentition, peak incidences for boys are found to be at 9 to 10 years, when energetic playing and sporting activities become more popular (Figure 2) — a scenario similar to what the author has been presented with.

Case presentation

Case presentation

This article aims to discuss the immediate management of a 10-year-old who had knocked out his upper central incisor 45 minutes before attending the dental surgery.

In order for the author to determine the best course of treatment for this case, it is very important to elicit careful medical, dental, and accident history. The author would use the clinical records, which allows the recording of clinical and historical data associated with the injury, ensuring no pertinent information has been missed (Andreasen, et al., 2003). Another important reason for good dental records in trauma cases is the possibility of legal action on the part of the parent, guardian, or patient.

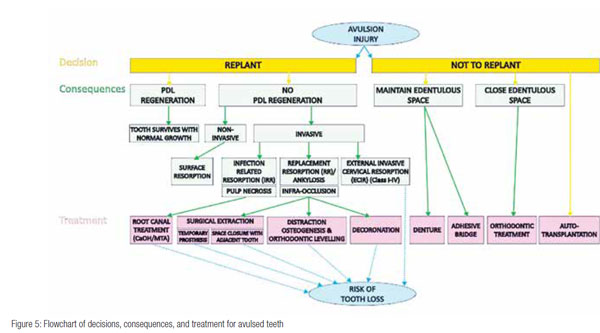

Several options exist for managing this case (Figure 5). The simplest long-term solution is to replant it. In 1980, Andreasen found that in monkeys, under ideal conditions, complete healing of the pulp and perio-dontal ligament (PDL) of replanted teeth can occur. However, the success of replantation depends on appreciating and working with the human biological processes.

Table 1 illustrates the factors that need to be considered in optimum patient management. The author will consider each of these factors in order to determine how best to treat this 10-year-old boy. The aims of this treatment are to re-establish normal tooth position (esthetically pleasing tooth form, color, and gingival contour) and tooth function (able to incise food without pain and mobility).

Tooth factors

The health of the pulp and periodontal ligament (PDL) are the key tissues that affect the prognosis of the avulsed tooth (Andreasen, et al., 2003). PDL cells are critical in allowing the tooth to reattach back into the socket. When there is too much damage to the ligament, healing occurs by bony replacement, and the tooth is replaced by bone and lost over a few years. This is known as “bony healing”/ankylosis/replacement resorption (RR) (Andreasen, 2007). Pulpal cells help fight against infection, necrosis, and, in turn, prevent inflammatory resorption (Andreasen, et al., 2003).

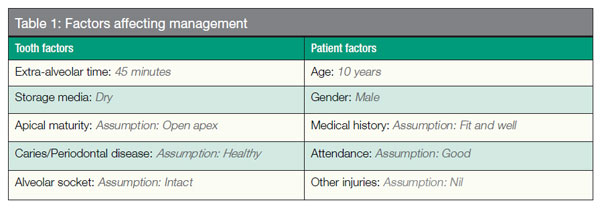

Immediately after avulsion, both pulpal and PDL cells begin to suffer ischemic injury, which can be worsened by drying, bacteria, and chemical irritants. These factors cause the loss of vitality to these PDL cells and dehydration to the pulpal cells, which are invaluable for tooth survival (Andreasen, et al., 2003; Barrett, Kenny, 1997; Gregg, Boyd, 1998; Andreasen, et al., 1995). Figure 3 illustrates that as the dry extra-alveolar time is increased, both the pulp and PDL healing is reduced.

Numerous studies by Andreasen, et al., in 1995 have shown the treatment outcome is strongly dependent upon:

- Extra-alveolar time

- Storage media

Andreasen, et al. (1995), demonstrated in a clinical study that immediate replantation (within 5 minutes) was one of the most critical factors necessary for PDL regeneration and return to normal function. Andersson and Bodin (1990) discovered that teeth replanted within 15 minutes have a favorable long-term prognosis, and most teeth replanted within 10 minutes experienced no resorption.

More recently, it has been found that dry storage of greater than 15 minutes causes precursor cells on the root side of the PDL to fail to reproduce and differentiate into fibroblasts (Kenny, Barrett, Casas, 2003). Even if the avulsed tooth is then placed in a liquid medium prior to replantation, this results in the unfavorable “repair” as opposed to the favorable “regeneration” and leads to ankylosis, root resorption, and eventual tooth loss (Donaldson, Kinirons, 2001).

Thus, ideally, replantation at the site of the injury leads to the best long-term prognosis. Hence, education or information of dental trauma care among teachers, coaches, caregivers, parents, medical personnel and, above all, dentists, is essential. A study in 2001 by Blakytny, et al., showed the reasons for reluctance in replantation among teachers, coaches, and caregivers were the following:

- Inadequate training

- Reluctant to induce pain/fear in child

- Fear of blood-borne infection

- Fear of incorrect replacement

- Fear of legal consequences

Storage medium

The storage medium prior to replantation has a great effect on root resorption and pulpal healing.

The author is presented with 45 minutes dry extra-alveolar time. Hence, during history taking and examination, if the avulsed tooth is not in a wet medium, the author would immediately place the tooth in fresh milk packed in ice to prevent further drying. The tooth would be carefully handled to avoid further PDL damage.

Complications such as root resorption are a great danger to tooth prognosis with an occurrence of 50% to 76% when the clinical conditions are far from ideal (Andreasen, et al., 1995). Other mediums the author could consider follow:

- Patient’s own saliva: In the author’s opinion, each case should be individually assessed. Risk of aspiration/swallowing should be taken into consideration. It should also be noted that this might not be pleasant for the child after a traumatic injury.

- Milk packed in ice: Maintains the ability of the precursor cells to reproduce twice as long as milk at room temperature (Kenny, et al., 2003).

- Hank’s balanced salt solution: balanced isotonic salt solution reconstitutes depleted cellular metabolites. Not readily available.

- Tissue culture medium (ViaSpan®): Tissue culture medium. Not readily available.

- Bioactive substances (enamel matrix derivative, Straumann® Emdogain™): Facilitates PDL regeneration. Further research required.

Tap water is an unsatisfactory medium, as it ruptures PDL cells through osmosis (DPB, 1999).

Apical maturity

The root of an upper central incisor completes its formation when the child is 10 years old. The guidelines the author will follow for the treatment of this tooth will depend on whether the root apex is open or closed. In this particular case, the author will assume that the apex is open.

Figure 4 shows that replanted immature teeth had less than 50% survival after 10 years. More teeth survived with closed apices (Andreasen, et al., 2003). Barrett and Kenny (1997) also found that replanted incisors with open apices had a significantly reduced survival, and the relative risk of failure was 4.2 times greater in immature than in mature incisors. The author will assume that the avulsed tooth is caries free and in good periodontal health, and that the alveolar wall is intact.

Patient factors

This avulsion injury has occurred at an age that is crucial to the patient’s facial growth and psychological development. Jaw growth varies noticeably with individual growth, which is not automatically linked with chronological age. Numerous studies have shown that it is hard to define the ideal time for implantation in relation to jaw growth (Lux, et al., 2012).

The optimum time for implantation is when the growth has terminated, which can be determined by taking repeated cephalographs/radiographs. This can be planned when considering placing implants; however, when the patient presents unscheduled with an avulsed tooth, the clinician does not have this privilege of time on his/her side.

The risk of replantation in this growing boy is ankylosis and subsequent interference with alveolar growth resulting in infra-occlusion. Nonetheless, in the author’s opinion, even maintaining the tooth to maintain the surrounding bone for a few years is considered successful.

Kawanami, et al. (1999), found that young girls had a higher risk of infraposition than young boys. However, a more recent study by Petrovic and colleagues in 2010 did not support this finding. More research is required to explore this interesting area.

Kawanami, et al. (1999), found that young girls had a higher risk of infraposition than young boys. However, a more recent study by Petrovic and colleagues in 2010 did not support this finding. More research is required to explore this interesting area.

Replantation is contraindicated if the patient is immunosuppressed. If this was the case, the patient’s physician must be consulted, and follow-up appointments must be strictly obeyed. The author will assume the boy is fit and well and on no medications. Follow-up appointments are a must in avulsed replanted cases due to the potential complications of inflammatory resorption, ankylosis (associated infraocclusion), external cervical inflammatory root resorption (ECIR), and discoloration. This should be stressed to the patient and his/her parent(s) or guardian(s).

Replantation is contraindicated if the patient is immunosuppressed. If this was the case, the patient’s physician must be consulted, and follow-up appointments must be strictly obeyed. The author will assume the boy is fit and well and on no medications. Follow-up appointments are a must in avulsed replanted cases due to the potential complications of inflammatory resorption, ankylosis (associated infraocclusion), external cervical inflammatory root resorption (ECIR), and discoloration. This should be stressed to the patient and his/her parent(s) or guardian(s).

The author will assume there are no other severe injuries that warrant favored emergency treatment. Figure 5 is a flow-chart outlining consequences and treatment options of replanting versus not replanting.

The author also has an ethical dilemma of whether to replant or not. The authors’ duties of care are (General Dental Council, 2005):

- Put patients’ interests first and act to protect them.

- Respect patients’ dignity and choices.

Therefore, this decision-making process should involve the parent(s) and the child. They should understand that a decision needs to be made promptly and will follow with consequences (Figure 5).

The goal for replanting this still-developing (immature) tooth is to allow for possible revascularization of the pulp and continued root development. Due to the dry time being less than 60 minutes and having considered all the above factors, the author feels obliged to replant the tooth. Despite the lower predictive success rate, there is still that chance of survival. Therefore, if the parent and child consent, the author will replant.

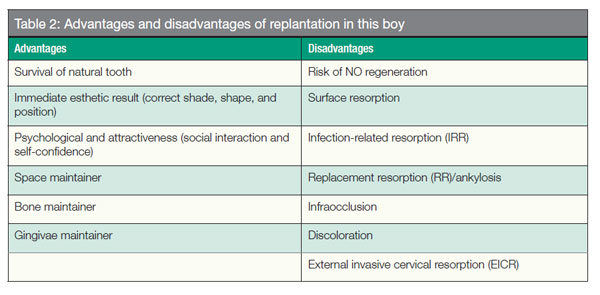

It must be stressed if there are obvious signs of failure, root canal treatment would be recommended. Furthermore, the risk of replacement resorption and subsequent tooth loss is high (as discussed previously, 45 minutes dry time, no wet storage media, open apex, and the increased risk of infraocclusion related to ankylosis). The advantages and disadvantages of replantation in this 10-year-old boy are listed in Table 2.

There are numerous guidelines published for the management of avulsed teeth (examples include the American Association of Endodontists, Dental Trauma Guide, International Association of Dental Traumatology, British Society of Paediatric Dentistry, and guidelines from the Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry), all of which are similar in content and widely followed to aid the practitioner to deliver optimum care at a timely manner.

However, all the guidelines have a major shortcoming. None have been tested by a formal clinical trial nor have they provided specific outcome information — i.e., there is little evidence to back up the protocols (discussed later). The author will follow the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) (2004) guidelines to manage this case.

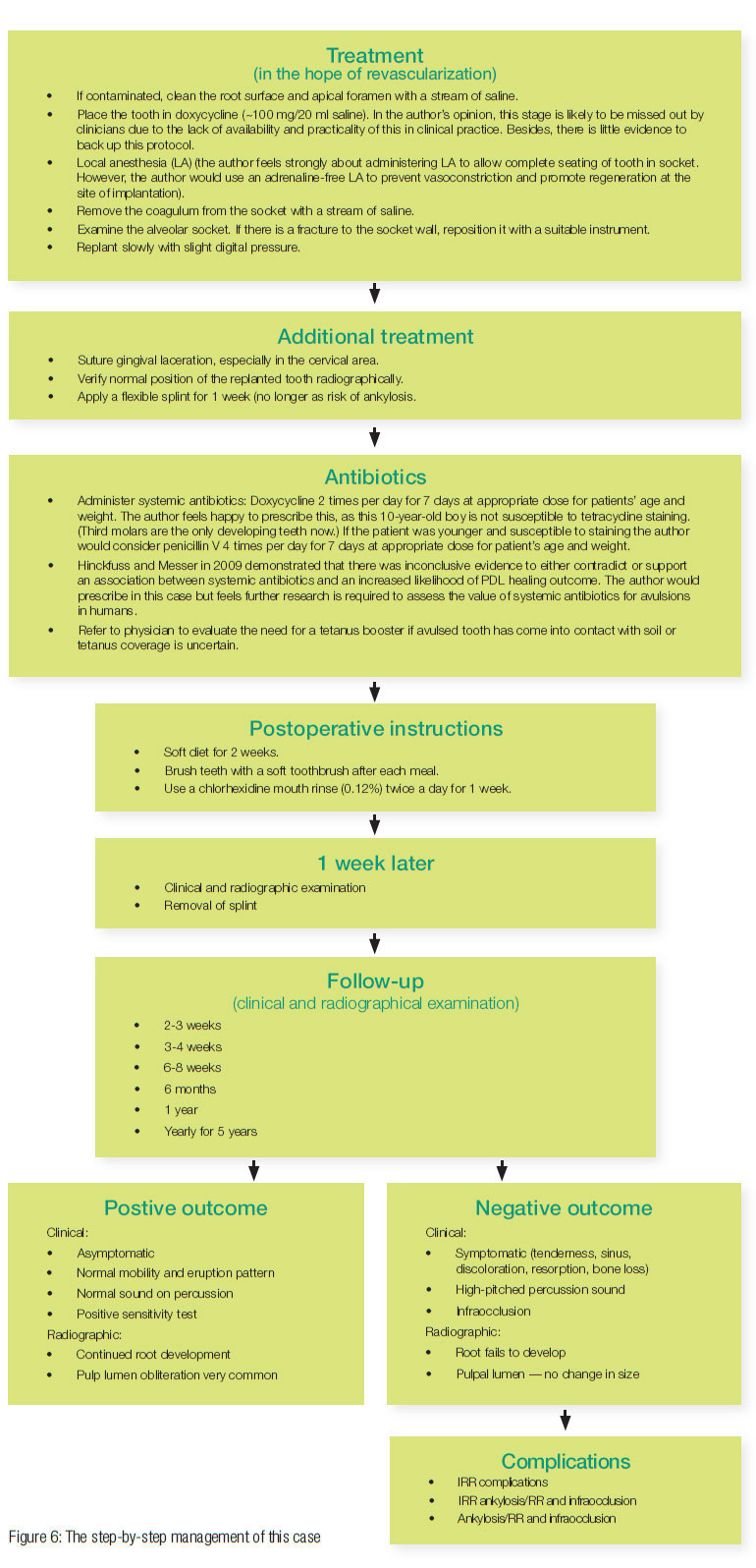

The step-by-step management of this case is demonstrated in Figure 6.

Comparison of guidelines

Comparison of guidelines

The Dental Trauma Guide guidelines are contrary to the AAE guidelines in the following aspects.

Splint removal in 2 weeks as opposed to 1 week

A systematic review carried out by Hinckuss and Messer (2009) found that there was inconclusive evidence for an association between short-term splinting (14 days) and an increased likelihood of functional periodontal healing, acceptable healing, or decreased development of replacement resorption. Further research is required — until then, the author would abide by the AAE guidelines.

Minocycline hydrochloride microspheres instead of doxycycline

Animal studies have shown that both these antibiotics enhance revascularization. The Dental Trauma Guide goes by studies carried out by Cvek, et al. (1990), and Yanpiset and Trope (2000), who found the benefits of doxycycline in monkeys’ and dogs’ teeth, respectively.

In 2004, Ritter, et al., found minocycline-covered dogs’ teeth before replantation proved to be successful. It is assumed that the positive effects with antibiotics will also occur in humans. Further research is required.

Less frequent follow-ups

Complications and long-term management (open apex)

Complications of replantation are common. Infection-related resorption (IRR) may be detected as early as 2 weeks post replantation. Ankylosis may be diagnosed 2 months later; however, it is more frequently detected after 6 months (Andreasen, et al., 1994). Thus, follow-up appointments are key to successful treatment.

Infection-related resorption

If obvious signs were present (Figure 6), the author would continue to follow the AAE guidelines and carry out immediate pulp extirpation and long-term dressing with calcium hydroxide. The status of the lamina dura and the presence of calcium hydroxide would be evaluated every 3 months until apexification.

In contrast, Trope (2011) recommends a disinfection procedure with a triple antibiotic paste and a “non-vital” revitalization procedure. If this technique fails, the more traditional apexification technique is advised with long-term calcium hydroxide or an apical plug with MTA.

It is important to note that IRR may be arrested by the preceding treatment, which removes the source of inflammation, but ankylosis may still occur due to the irreversible damage to the PDL. A very interesting find by some studies have shown that the presence of calcium hydroxide may increase the occurrence of ankylosis (British Society of Pediatric Dentistry, 1999).

Ankylosis and infraocclusion

Ankylosis and infraocclusions is a likely consequence for this 10-year-old growing boy. Ankylosis can lead to infraocclusions and difficult extractions; both of which are undesirable as they leave a large buccal defect, resulting in major esthetic challenges at final prosthetic replacement.

A more recent technique of “decoronation” is based on experimental and clinical studies and has shown to be quite an effective way to manage an ankylosed tooth (Cohenca, Stabholz, 2007). The author would adopt this technique if the 10-year-old were faced with this situation.

When the tooth is infraoccluded for about 2 mm, the crown should be removed and the root below the cement-enamel junction (CEJ) submerged, leaving the root to be slowly replaced by bone preventing the collapse of the socket. In addition, the bone will now grow above the submerged root to the level of the CEJ’s of the adjacent teeth.

In this way the height and width of the bone and gingival architecture is maintained, allowing for an esthetically pleasing prosthetic rehabilitation. Other complications include surface resorption (self-limiting) and ECIR (relatively uncommon).

Closed apex

There is no chance of revascularization and an increased risk of IRR. Thus, there are two main differences in the treatment protocol to prevent this:

- Initiation of endodontic treatment 1 week after replantation

- Higher dose of penicillin

Conclusion

The author has described the immediate and long-term management of an avulsed tooth. An avulsed tooth presents many questions to the treating dentist. The most significant factor in success is immediate replantation for both pulpal and periodontal healing.

Studies have shown gaps in knowledge when managing avulsions. The author feels there is a need to introduce educational campaigns to broaden knowledge of emergency protocols and to prevent trauma in the first instance.

References

- Abu-Dawoud M, Al-Enezi B, Andersson L. Knowledge of emergency management of avulsed teeth among young physicians and dentists. Dent Traumatol. 2007; 23(6):348-355.

- American Association of Endodontists (AAE). Recommended Guidelines of the American Association of Endodontists for the Treatment of Traumatic Dental Injuries. Chicago, IL: 2004.

- Andersson L, Bodin I. Avulsed human teeth replanted within 15 minutes — a long-term clinical follow-up study. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990; 6(1):37-42.

- Andreasen JO A time-related study of periodontal healing and root resorption activity after replantation of mature permanent incisors in monkeys. Swed Dent J. 1980; 4(3): 101-110.

- Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L. Avulsions. In: Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2007.

- Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Bakland LK, Flores MT. Traumatic Dental Injuries: A Manual. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Munksgaard; 2003.

- Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Jacobsen HL, Andreasen FM. Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 1. Diagnosis and healing complications. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1995;11(2): 51-58.

- Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Jacobsen HL, Andreasen FM. Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 2. Factors related to pulp healing. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1995;11(2): 59-68.

- Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Andreasen FM. Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 3. Factors related to root growth after replantation. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1995;11(2):69-75.

- Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Jacobsen HL, Andreasen FM. Replantation of 400 avulsed permanent incisors. 4. Factors related to periodontal ligament healing. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1995;11(2):76-89.

- Bakland LK, Andreasen JO. Dental traumatology: essential diagnosis and treatment planning. Endod Topics. 2004;7:14-34.

- Barrett EJ, Kenny DJ. Avulsed permanent teeth: a review of the literature and treatment guidelines. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13(4):153-163.

- Barrett EJ, Kenny DJ. Survival of avulsed permanent maxillary incisors in children following delayed replantation. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13(6):269-275.

- Blakytny C, Surbuts C, Thomas A, Hunter ML. Avulsed permanent incisors: knowledge and attitudes of primary school teachers with regard to emergency management. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(5):327-332.

- British Society of Paediatric Dentistry (BSPD). Paediatric Dentistry UK: National clinical guidelines and policy documents. Dental Practice Board for England and Wales: 1999.

- Chappuis V, von Arx T. Replantation of 45 avulsed permanent teeth: a 1-year follow-up study. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21(5):289-296.

- Cohenca N, Stabholz A. Decoronation — a conservative method to treat ankylosed teeth for preservation of alveolar ridge prior to permanent prosthetic reconstruction: literature review and case presentation. Dent Traumatol. 23(2):87-94.

- Cvek M, Cleaton-Jones P, Austin J, Lownie J, Kling M, Fatti P. Effect of topical application of doxycycline on pulp revascularization and periodontal healing in reimplanted monkey incisors. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1990;6(4)48-56.

- Day P, Duggal M. Interventions for treating traumatised permanent front teeth: avulsed (knocked out) and replanted. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;20(1):CD006542.

- de Souza RF, Travess H, Newton T, Marchesan MA. Interventions for treating traumatised ankylosed permanent front teeth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 20(1):CD007820

- Donaldson M, Kinirons MJ. Factors affecting the time of onset of resorption in avulsed and replanted teeth in children. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17(5):205-209

- Flores MT, Andersson L, Andreasen JO, et al. International Association of Dental Traumatology. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. II. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23(3):130-136.

- General Dental Council. Principles of Patient Consent. London, UK: 2005. [online] Available at: <https://www.gdc-uk.org/Dentalprofessionals/Standards/Documents/PatientConsent[1].pdf>

- Glendor U. Has the education of professional caregivers and lay people in dental trauma care failed? Dent Traumatol. 2009;25(1):12-18.

- Gregg TA, Boyd DH. Treatment of avulsed permanent teeth in children. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry. Royal College of Surgeons, Faculty of Dental Surgery. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1998;8(1):75-81.

- Hecova H, Tzigkounakis V, Merglova V, Netolicky J. A retrospective study of 889 injured permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2010; 26(6):466-475.

- Hinckfuss SE, Messer LB. An evidence-based assessment of the clinical guidelines for replanted avulsed teeth. Part 2: Prescription of systemic antibiotics. Dent Traumatol. 2009; 25(2):158-164.

- Hinckfuss SE, Messer LB. Splinting duration and periodontal outcomes for replanted avulsed teeth: a systematic review. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25(2):150-157.

- International Association of Dental Traumatology. The Dental Trauma Guide. 2010) [online] Available at: <www.dentaltraumaguide.org>

- Kawanami M, Andreasen JO, Borum MK, Schou S, Hjorting-Hansen E, Kato H. Infraposition of ankylosed permanent maxillary incisors after replantation related to age and sex. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1999;15(2):50-56.

- Kenny DJ, Barrett EJ, Casas MJ. Avulsions and intrusions: the controversial displacement injuries. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003; 69(5):308-113.

- Lux HC, Goetz F, Hellwig E. Case report: endodontic and surgical treatment of an upper central incisor with external root resorption and radicular cyst following traumatic tooth avulsion. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2012;110(5):e61-e67.

- McIntyre JD, Lee JY, Trope M, Vann WF Jr. Management of avulsed permanent incisors: a comprehensive update. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29(1):56-63.

- Petrovic B, Markovic D, Peric T, Blagojevic D. Factors related to treatment outcomes of avulsed teeth. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26(1):52-59.

- Pohl Y, Filippi A, Kirschner H. Results after replantation of avulsed permanent teeth. I. Endontic considerations. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21(2):80-92.

- Pohl Y, Filippi A, Kirschner H. Results after replantation of avulsed permanent teeth. II. Periodontal healing and the role of physiologic storage and antiresorptive-regenerative therapy. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21(2):93-101.

- Pohl Y, Wahl G, Filippi, A, Kirschner H. Results after replantation of avulsed permanent teeth. III. Tooth loss and survival analysis. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21(2):102-110.

- Protocols for clinical pediatric dentistry: solutions to clinical problems from the Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry (1995) Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry 3: 26-30

- Ritter AL, Ritter AV, Murrah V, Sigurdsson A, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of replanted immature dog teeth after treatment with minocycline and doxycycline assessed by laser Doppler flowmetry, radiography, and histology. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20(2):75-84.

- Roberts G, Longhurst P. Oral and Dental Trauma in Children and Adolescents. 1st ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 1996.

- Rosenberg H, Rosenberg H, Hickey M. Emergency management of a traumatic tooth avulsion. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(4):375-377.

- Trope M. Avulsion of permanent teeth: theory to practice. Dent Traumatol. 2011;27(4):281-294.

- de Vasconcellos LG, Brentel AS, Vanderlei AD, de Vasconcellos LM, Valera MC, de Araújo MA. Knowledge of general dentists in the current guidelines for emergency treatment of avulsed teeth and dental trauma prevention. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25(6):578-583.

- Wikipedia (2012) Dental avulsion. [online] Available at <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dental_avulsion> [Accessed 24/03/2012]

- Yanpiset K, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of replanted immature dog teeth after different treatment methods. Endod Dent Traumatol. 2000;16(5):211-217.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..