CE Expiration Date: December 21, 2026

CEU (Continuing Education Unit):2 Credit(s)

AGD Code: 070

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to discuss the clinical significance of sealing lateral anatomical structures with sealer and explore the correlation between the presence of a lateral canal filling with sealer and the overall healing of the accompanying periradicular lesion.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz online at endopracticeus.com to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize the complexity of the root canal system and complexity in completely sterilizing it.

- Recognizing that disinfecting the root canal structures is important, especially in cases of pulp necrosis and apical and/or lateral periodontitis.

- Realize the value of the presence of a filled lateral canal or lateral sealer puff on the final image.

- Observe show how lateral canal fills and sealer puffs are able to tell a story about the pulp system anatomy and the etiology of lateral lesions.

- Identity how lateral canal fills and sealer puffs can confirm the effective debridement and three dimensional sealing of the root canal system.

Drs. Mahmood Reza Kalantar Motamedi and Brett E. Gilbert consider the importance of lateral canals and healing of the root canal system.

Drs. Mahmood Reza Kalantar Motamedi and Brett E. Gilbert discuss the clinical significance of sealing these lateral anatomical structures

In modern endodontic practice, the focus has shifted from traditional methods of cleaning, shaping, and filling to prioritizing conservative canal shaping first, to open the canals, and the use of advanced disinfection protocols with irrigation which enables more effective cleaning before three-dimensional filling.2

In an effort to be more accurate and descriptive of root canal anatomy, it is recommended to use the term “root canal system” instead of simply referring to a “root canal.” The path from the coronal orifice to the apical terminus is not a straight and single route, and there are various accessory pathways throughout the system.2 Ramifications and accessory anatomy are found in different parts of the root, with 73.5% in the apical third, 11% in the middle third, and 15% in the coronal third.3

The complex structure of the root canal system makes it impossible for any known technique, whether chemical or mechanical, to completely sterilize it. Therefore, the objective of treatment should be to remove biological tissues and reduce microbial contamination as much as possible followed by creation of an effective three-dimensional seal to encapsulate any remaining microorganisms.1

Lateral canals leading to portals of exit along the root surface at various locations serve as potential pathways for bacteria or their byproducts to reach the periodontal ligament (PDL) and cause disease. Similarly, bacteria from periodontal pockets can reach the pulp from the outside in.4 Cleaning, disinfecting, and filling lateral canals and apical ramifications during treatment can be challenging and unpredictable. The clinical significance of sealing these lateral anatomical structures with sealer has long been a topic of debate among clinicians and researchers who ponder whether there is a correlation with the presence of a lateral canal filling with sealer and the overall healing of the accompanying periradicular lesion.

Is it necessary to clean and fill lateral canals?

Verification of the sealing of lateral canals and their portals of exit with sealer on imaging is a desirable objective of treatment by clinicians. The presence of the sealer in these spaces confirms that enough cleansing of the intracanal dentinal walls was accomplished during the root canal procedure. In reality, the only main significance of sealing these canal structures is when there is a chance that bacterial contamination from the inside of the canal system travels to the PDL, often resulting in a lateral lesion positioned at the portal of exit.4 However, clinical experience shows that lateral lesions can heal even without filling the lateral canals.4,5 A cadaver study by Barthel, et al., reported no relationship between unfilled lateral canals and inflammation in the surrounding tissues.6

However, it must be stated that lateral canals and apical ramifications have been implicated with endodontic treatment failure when they are sufficiently large enough to harbor significant numbers of bacteria and to provide these bacteria with unimpeded access to the periradicular tissues.4 Therefore, disinfecting these structures is important in cases of pulp necrosis and apical and/or lateral periodontitis. Efforts should be made to incorporate therapeutic strategies that target these areas during the disinfection process.

In clinical practice, while filling lateral canals may not always be necessary for success, the presence of a filled lateral canal or lateral sealer puff on the final image can provide valuable confirmation that a lesion is a lesion of endodontic origin. This phenomenon indicates that the canal system walls have been debrided well enough to expose the lateral canal opening inside of the root wall and allow for sealer to flow into and through the lateral canal portal of exit reaching the lateral lesion. The presence of a sealed lateral canal can be valuable in terms of providing a more accurate prognosis for a given case. In essence, we can extrapolate that the sealer extrusion through the lateral canal to the coincident lesion serves as a storyteller to confirm a lesion is of endodontic origin and that sufficient cleaning was accomplished to allow for the flow of sealer into this space.

Lateral canal fills and sealer puffs are able to tell a story about the pulp system anatomy, the etiology of lateral lesions, and to confirm the effective debridement and three dimensional sealing of the root canal system.

In this study, we present some interesting case reports of lateral canals that were filled with sealer which extends into the lateral lesions. Our purpose is to show how these lateral canal fills and sealer puffs are able to tell a story about the pulp system anatomy, the etiology of lateral lesions, and to confirm the effective debridement and three dimensional sealing of the root canal system.

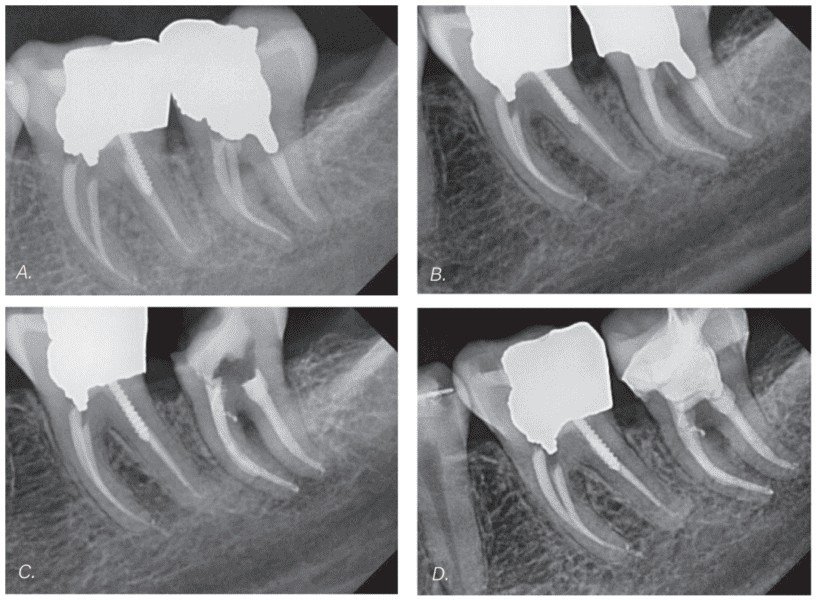

Case report 1

A 31-year-old male presented with a chronic abscess of tooth No. 18. Five years prior, primary root canal treatment was performed by author MM on this tooth, but it presented with post treatment disease. The coronal seal appears to be intact. There are no radiographic signs of periapical radiolucency or widening of the PDL (Figure 1A). However, there is a buccal sinus tract that was traced with gutta percha (GP) and extends towards the furcation (Figure 1B). This raised the suspicion of a crack, but probing depths were within normal limits. After discussing with the patient, it was decided to proceed with non-surgical orthograde retreatment. During the procedure, no crack was observed in the pulp chamber floor, so treatment continued. The previous root filling materials were removed, and 5% NaOCl was ultrasonically activated using UltraX (Eighteeth, Changzhou, China) to improve irrigation quality. The canals were then obturated using the warm vertical condensation technique and AH Plus® sealer (Dentsply DeTrey, Konstanz, Germany; Dentsply Sirona). This case was completed in a single visit. Immediately after obturation, a lateral sealer puff was observed in the area previously traced with GP (Figure 1C). This may indicate the origin of the endodontic lesion and the reason for the failure of the previous treatment. One-year postoperative radiograph shows a normal periapical appearance, and the tooth is functional and asymptomatic (Figure 1D).

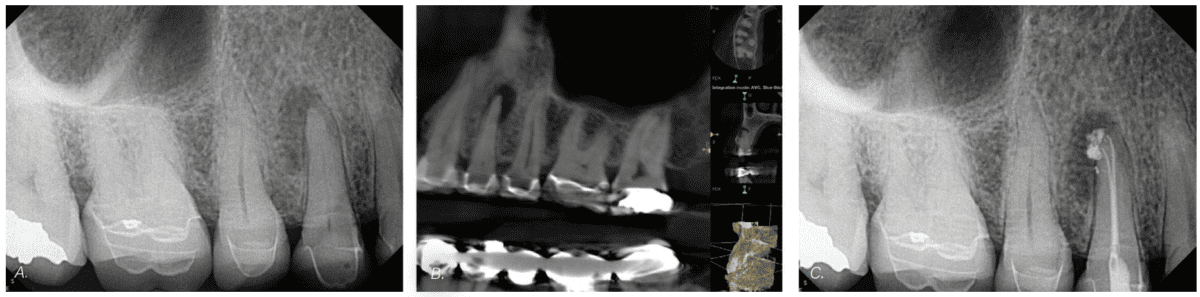

Case report 2

A 64-year-old female patient presented with pain to biting tooth No. 5. An enlarged apical lesion was noted extending coronally to the mid-root level on the distal (Figures 2A and 2B). Diagnosis for tooth No. 5 was pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis. Root canal treatment was completed using rotary instruments to a final canal preparation size of 18/.04 in the buccal and palatal canals with ExactTaperH DC™ (SS White Dental, Lakewood, New Jersey). Copious irrigation was achieved with Triton® (Brasseler USA, Savannah, Georgia) and activation with laser-assisted endodontic irrigation protocol using the EdgePro™ laser (EdgeEndo, Albuquerque, New Mexico). Obturation was accomplished with GP and BC HiFlow™ sealer (Brasseler USA, Savannah, Georgia) using a single cone hydraulic condensation technique. A permanent access filling was placed. This case was completed in a single visit. Two portals of exit are noted curving toward the distal aspect, and a third lateral portal of exit is visible more coronally and is visible with a sealer fill (Figure 2C). The visual confirmation of the lateral canal portal of exit tells a story of anatomy and etiology providing context and understanding as to the etiology of the large lesion as a manifestation of the intracanal pulpal necrosis extruding into the PDL space via the lateral canal on the distal side of the root.

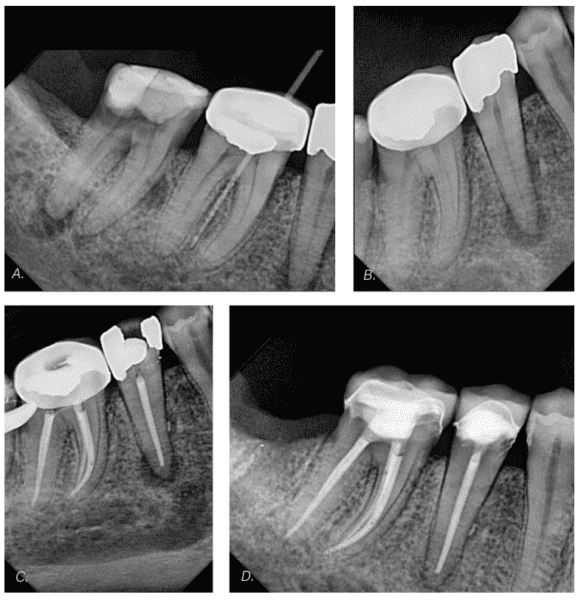

Case report 3

An 80-year-old female presented with a chronic apical abscess. Tracing of the sinus tract revealed the responsible tooth was tooth No. 30 (Figure 3A). However, both adjacent teeth, Nos. 29 and 31, were also necrotic with asymptomatic apical periodontitis. Unfortunately, tooth No. 31 was not salvageable due to heavy destruction of the crown, and it was referred for extraction.

After administering local anesthesia and isolating with a dental dam, access cavities were prepared for both teeth Nos. 29 and 30 at the same time (in this case report, we are only focusing on tooth No. 29). Throughout the root canal instrumentation, the irrigant of choice was 5% NaOCl. A crown-down approach was performed with T-Pro rotary files (Shenzhen Perfect Medical Instruments Co. Ltd., Guangdong, China). The final preparation size of the root canal for tooth No. 29 was 40/.04. NaOCl was activated with UltraX for a few minutes before obturation. Due to the close proximity of the apex of tooth No. 29 to the mental foramen, the master GP cone was placed 1 mm short of the working length along with the least amount of AH Plus sealer. Warm vertical obturation technique was carried out. Post-obturation radiograph revealed a small amount of sealer extrusion from a lateral canal toward the lateral lesion. The tooth was temporized and referred for permanent restoration. A follow-up of 3 months shows a favorable healing of periradicular lesion and complete resolution of the sinus tract.

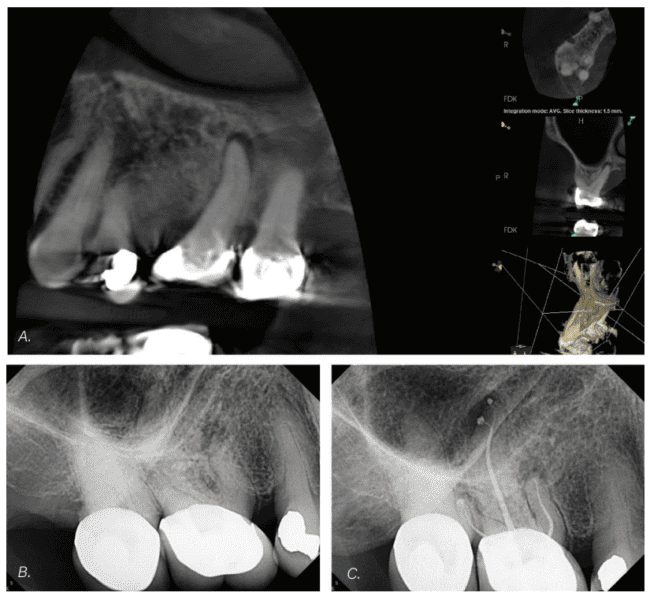

Case report 4

A 72-year-old female patient presents for pain in the upper right quadrant for 1 week, which was exacerbated by biting pressure. The diagnosis was tooth No. 3 pulp necrosis with symptomatic apical periodontitis. An enlarged apical lesion was noted on the palatal root extending coronally within the apical third of the palatal root on the distal (Figures 3A and 3B). RCT was completed using rotary instruments to a final canal preparation size of 18/.04 in the mesiobuccal and distobuccal canals (no second mesiobuccal canal was present) and to a size 30/.04 in the palatal canal with ExactTaperHDC. Copious irrigation was done with Triton and activation with a laser-assisted endodontic irrigation protocol using the EdgePro laser and obturation with GP and BC Hi Flow sealer using a single cone hydraulic condensation technique. A permanent access filling was placed.

This case was completed in a single visit. The primary portal of exit on the palatal canal was directed toward the distal and a lateral portal of exit on the distal aspect of the palatal root in the apical third was noted on the final image (Figure 4C). The visual confirmation of the lateral canal tells the story of the reality of the pulp system anatomy, and etiology providing context and confirmation that this is a lesion of endodontic origin, and its position on the distal aspect of the palatal root was directed by the location of the lateral portal of exit of the necrotic canal.

Discussion

Lateral canals are typically not visible in preoperative radiographs, except in cases where there is localized thickening of the PDL on the root’s lateral surface or the presence of a lateral periodontal lesion.4 Use of cone beam computed tomography can help to identify these structures in some cases. Lateral canal anatomy can be visualized on radiographs after root canal obturation when root filling material is forced into the ramifications, a phenomenon that we consider a “storyteller,” highlighting pulpal system anatomy and verification of the etiology of lateral periradicular lesions.

The complete cleaning of these ramifications, without leaving any tissue residue or infected debris, is a challenge. Complete cleaning of accessory or lateral canals is not likely feasible.7 However, in endodontic practice, the goal is to minimize the intracanal bacterial load as much as possible, and visual evidence of lateral sealer puffs helps to confirm this has occurred during treatment.

If the pulpal tissue in these accessory innervations is necrotic and infected, leading to apical and lateral periodontitis, it becomes crucial to thoroughly clean and disinfect these lateral canals rather than simply filling them with an inert material. The shaping phase alone cannot reach these spaces, highlighting the importance of irrigation in three-dimensional cleaning. After shaping, the use of irrigants such as sodium hypochlorite and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), along with various activation techniques like subsonic activation, sonic activation, ultrasonic activation, and laser-assisted and multisonic activation can aid in the removal of pulp tissue remnants and hard tissue debris. A highly effective technique that does not require expensive devices for activation of irrigation is the ultrasonic activation technique.8

Once the main root canal is adequately cleaned, it is ready for obturation. Based on some studies, warm obturation techniques can effectively fill the previously cleaned lateral canals.9,10 Moreover, high-flow sealers can be helpful to fill lateral canals. In the cases presented in this study, BC sealer with single-cone hydraulic condensation technique or AH-plus sealer with warm vertical condensation technique were utilized for obturation.

Summary

Based on the literature, it appears that cleaning the lateral canals is more important than filling them. However, in clinical practice, when we observe the final image and see the sealer protruding into the lateral lesion, it indicates and confirms that the lesion originated from extrusion of necrotic debris from the lateral canal. This also suggests that the lateral canal has been cleaned to a significant enough extent for the sealer to pass through. It is more likely that sealer travels through a lateral canal that has been cleaned rather than a non-cleaned one. This tells the clinician a story confirming the presence of lateral anatomy and the likelihood that in necrotic cases, a periradicular lesion laterally adjacent to the root is of endodontic origin.

Dr. Gilbert has written on many topics for Endodontic Practice US, from lateral canals to irrigation, and more. Read more about what brought him to the specialty here: https://endopracticeus.com/brett-e-gilbert-dds/

References

- Carrotte P. Endodontics: Part 1. The modern concept of root canal treatment. Br Dent J. 2004 Aug 28;197(4):181-183.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal – A sign of superiority? J Dent Sci. 2020 Dec;15(4):562-563.

- Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology 1984;58(5):589-99. Vertucci FJ. Root canal anatomy of the human permanent teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984 Nov;58(5):589-599.

- Ricucci D, Siqueira JF Jr. Fate of the tissue in lateral canals and apical ramifications in response to pathologic conditions and treatment procedures. J Endod. 2010 Jan;36(1):1-15.

- Camps J, Lambruschini GM. L’obturation des canaux latéraux: nécessité thérapeutique ou satisfaction radiologique? [Obturation of lateral canals: necessary therapy or radiological satisfaction?]. Rev Fr Endod. 1991 Jun;10(2):19-26. French.

- Barthel CR, Zimmer S, Trope M. Relationship of radiologic and histologic signs of inflammation in human root-filled teeth. J Endod. 2004 Feb;30(2):75-79.

- Siqueira JF Jr, Araújo MC, Garcia PF, Fraga RC, Dantas CJ. Histological evaluation of the effectiveness of five instrumentation techniques for cleaning the apical third of root canals. J Endod. 1997 Aug;23(8):499-502.

- Retsas A, Boutsioukis C. An update on ultrasonic irrigant activation. ENDO: Endodontic Practice Today. 2019;13(2):115-129.

- DuLac KA, Nielsen CJ, Tomazic TJ, Ferrillo PJ Jr, Hatton JF. Comparison of the obturation of lateral canals by six techniques. J Endod. 1999 May;25(5):376-380.

- Carvalho-Sousa B, Almeida-Gomes F, Carvalho PR, Maníglia-Ferreira C, Gurgel-Filho ED, Albuquerque DS. Filling lateral canals: evaluation of different filling techniques. Eur J Dent. 2010 Jul;4(3):251-256.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..

Mahmood Reza Kalantar Motamedi, DDS, MSc, received his dental degree from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran in 2014. He completed his postgraduate program in endodontics at Azad University in Isfahan, Iran in 2020. He regularly teaches endodontics to general dentists and holds hands-on courses. In addition, he operates a private endodontics practice in Isfahan, Iran.

Mahmood Reza Kalantar Motamedi, DDS, MSc, received his dental degree from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran in 2014. He completed his postgraduate program in endodontics at Azad University in Isfahan, Iran in 2020. He regularly teaches endodontics to general dentists and holds hands-on courses. In addition, he operates a private endodontics practice in Isfahan, Iran. Brett E. Gilbert, DDS, FICD graduated from the University of Maryland Dental School (DDS 2001, Endo, 2003). He is a professor in the Department of Endodontics at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics and founder of Access Endo and the Access Endo Impact Academy. He is a partner in Specialized Dental Partners and serves on the EPIC Clinical Advisory Board. He has a private practice, King Endodontics PLLC, in Niles, Illinois.

Brett E. Gilbert, DDS, FICD graduated from the University of Maryland Dental School (DDS 2001, Endo, 2003). He is a professor in the Department of Endodontics at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics and founder of Access Endo and the Access Endo Impact Academy. He is a partner in Specialized Dental Partners and serves on the EPIC Clinical Advisory Board. He has a private practice, King Endodontics PLLC, in Niles, Illinois.