Dr. John Lordan examines how to achieve profound pulpal anesthesia in teeth with irreversible pulpitis

Successful anesthesia in mandibular molar teeth is challenging under normal pulpal conditions but particularly so when the patient presents with a symptomatic acutely inflamed pulp. This will not surprise any operating dentist who faces the challenge of trying to operate on a patient who cannot tolerate the procedures due to lack of profound anesthesia. It is important to realize that the inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) has deficiencies in providing the desired level of pulpal anesthesia in normal pulps and could be considered not fit for purpose in acutely inflamed pulp situation (Vreeland, et al., 1989; Wali, et al., 1988).

Educational aims and objectives

This clinical article aims to investigate achieving profound pulpal anesthesia.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions in the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Realize that intraligamental and intraosseous techniques are very successful in achieving profound pulpal anesthesia.

- Recognize that these techniques should be considered as part of the routine approach.

- Identify a specific mandibular anesthesia protocol.

It is well established that complete pulpal anesthesia is not achieved 100% of the time in normal pulps, and that lip numbness does not confirm pulpal anesthesia. In fact, confirmed 100% lip numbness after IANB in inflamed pulps reported only 55% successful pulpal anesthesia. There are multiple theories on the reasons for failure, and the reality is that a combination of factors are involved (Nusstein, et al., 1998; Cohen, et al., 1993).

There are many theories on what causes anesthetic failure in acutely inflamed pulps, such as increased blood flow in inflamed tissues and lowered pH locally interfering with LA solution activity (Hargreaves, Keiser, 2002). Accessory innervation from mylohyoid nerve has also been mentioned (Vandermeulen, 2000). The presence of inflammatory mediators such as substance P and calcitonin neuropeptides also reduces the effect of local anesthetic (Rood, et al., 1981). Nerve sprouting also occurs in inflamed tissues, increasing the volume of nerve tissue to be anesthetized (Hargreaves, 2001). The central core theory (de Jong, 1997; Strichartz, 1976) states that the outer nerves of the inferior alveolar bundle supply the molar teeth, whereas the nerves for the anterior teeth lie more deeply, making it more difficult for the anesthetic to diffuse through and provide an adequate block.

There are many theories on what causes anesthetic failure in acutely inflamed pulps, such as increased blood flow in inflamed tissues and lowered pH locally interfering with LA solution activity (Hargreaves, Keiser, 2002). Accessory innervation from mylohyoid nerve has also been mentioned (Vandermeulen, 2000). The presence of inflammatory mediators such as substance P and calcitonin neuropeptides also reduces the effect of local anesthetic (Rood, et al., 1981). Nerve sprouting also occurs in inflamed tissues, increasing the volume of nerve tissue to be anesthetized (Hargreaves, 2001). The central core theory (de Jong, 1997; Strichartz, 1976) states that the outer nerves of the inferior alveolar bundle supply the molar teeth, whereas the nerves for the anterior teeth lie more deeply, making it more difficult for the anesthetic to diffuse through and provide an adequate block.

Achieving profound pulpal anesthesia is the cornerstone

of successful endodontics, and this poses challenges in teeth

with irreversible pulpitis, particularly mandibular molars.

Central nervous system sensitization can also occur where inflammatory conditions have existed for some time, as in slow onset pulpitis. It is safe to say that some of the reasons for failure are often related to physiological factors and not just anatomy with decreased excitability thresholds on nerves compounded by an increased anxiety in those patients in pain (Cohen, et al., 1993; Hargreaves, et al., 2002). This can result in an innocuous stimulus presenting as painful in a patient who has been subject to central sensitization due to long-term exposure to discomfort.

Patients presenting with irreversible pulpitis are often aware of symptoms for some time (weeks or months before) and may relate the discomfort to a restorative procedure such as composite filling placement or crown placement. Symptoms gradually become more severe with longer-lasting painful episodes occurring spontaneously and usually acute response to heat application relieved by cold and paroxysmal in nature.

Patients may have had difficulty sleeping and are usually fractious and fragile. Dental confidence is low, and so every effort must be explored to reassure patients that we are aware and understanding of their situation and that we have the experience and techniques to deal with their symptoms comfortably. Naturally, when IANB is successful — i.e., lip numbness established but pulpal anesthesia still not achieved — we need to take positive action rather than trying to proceed with treatment on a very anxious patient.

Preoperative oral administration of a non-steroidal analgesic, 800 mg ibuprofen, for example, can help improve the efficacy of local anesthetic in some cases (Ianiro, et al., 2007). Some patients may also benefit from oral diazepam — typically 10 mg-15 mg taken the night before appointment and 1 hour before treatment.

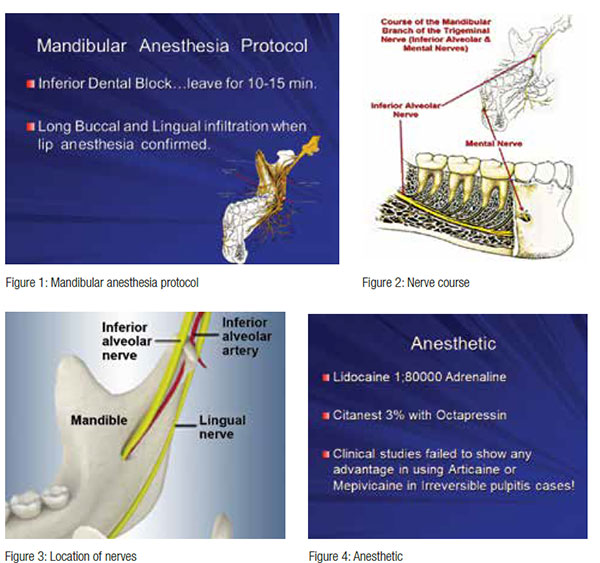

Mandibular anesthesia protocol

Inferior alveolar dental block is administered; wait for at least 15 minutes. Then once lip “numbness” is established and confirmed, follow up with buccal infiltration and lingual infiltration on attached gingiva (Figure 5). Evaluate anesthesia through electric pulp test (EPT) or cold test and advise the patient that you have facility for further anesthetic procedures at your disposal. And be prepared for this part of your routine preparation when supplementary anesthesia is indicated (Dreven, et al., 1987).

Patients presenting with acute pulpitic maxillary molars respond well to buccal and palatal infiltration, and profound anesthesia is readily achieved successfully. This confirms that, if you can place the anesthetic in close proximity to the root apex, the outcome is positive and anesthesia will be successful.

Anesthetic choice

The anesthetic of choice is Lignospan® 2% 1:000.000 for IANB injections. There are studies supporting the use of articaine with 1:100000 adrenaline administered by buccal infiltration as an alternative to inferior alveolar nerve block in normal pulps; however, in symptomatic teeth, there was no advantage in using articaine, and there are some dangers of paresthesia (>20 times) in its uses as IANB technique (Claffey, et al., 2004; Kanaa, et al., 2009). The lingual nerve is more frequently damaged than the inferior alveolar in these cases due to its location (Figure 3). Thankfully, 90% of cases fully recover within 2 months, but this is an avoidable risk.

Successful anesthesia in acutely inflamed pulps

Intraligamentary injections

Periodontal ligament injection has been shown to be successful in achieving anesthesia in 75% of cases in an initial application and up to 96% success in a second injection. Periodontal ligament injection is essentially a route into the cancellous spaces, so it is, in effect, an intraosseous injection. Different kits are available, but the needle should be placed in the gingival crevice with the bevel facing the root surface and the injection under pressure for 10 seconds at each corner of tooth. The rate of onset is fast, but the duration is low; application can be problematic and uncomfortable for patients as well as stressful for the operator (Cohen, et al., 1993; Walton, Abbott, 1981; Smith, et al., 1983).

Intraosseous injection

Intraosseous injections (Figures 6 and 7) deliver an anesthetic solution directly into the cancellous bone distal to the affected tooth. Stabident (Figure 8) and X-Tip™ (Dentsply) (Figure 9) systems are well established intraosseous systems that deliver anesthetic solutions directly into the cancellous bone via a predrilled pathway. The Stabident system provides a perforation bur with a separate needle that works well, providing the access hole is readily located, which is not always the case, necessitating a second perforation with associated increased anxiety. The X-Tip system solves this issue by leaving a guide sleeve in situ to guide the needle access (Figures 9 and 10), but this is a bulky system that requires practice to perfect. Difficulty separating the drill from the guide sleeve can be an issue, and the large diameter guide sleeve can generate higher temperatures during perforation of thicker, denser cortical bone, resulting in postoperative discomfort (Parente, et al., 1998; Parente, et al., 1998; Nusstein, et al., 1998).

Changing the anesthetic type or the block injection technique (Gow-Gates, Akinosi) does not improve the chances of success, and giving another inferior alveolar dental block (ID) will help only if the initial block has failed. Increasing the volume of the local anesthetic will not improve the pulpal anesthetic effect. It may, in fact, have the opposite effect due to tachyphylaxis where the anesthetic reaction becomes increasingly weaker due to “ion trapping” of the anesthetic in inflammation-induced acidic tissue (Gow-Gates, 1973; Claffey, et al., 2004; Mikesell, et al., 2005; Nusstein, et al., 2002; Goldberg, et al., 2008).

Changing the anesthetic type or the block injection technique (Gow-Gates, Akinosi) does not improve the chances of success, and giving another inferior alveolar dental block (ID) will help only if the initial block has failed. Increasing the volume of the local anesthetic will not improve the pulpal anesthetic effect. It may, in fact, have the opposite effect due to tachyphylaxis where the anesthetic reaction becomes increasingly weaker due to “ion trapping” of the anesthetic in inflammation-induced acidic tissue (Gow-Gates, 1973; Claffey, et al., 2004; Mikesell, et al., 2005; Nusstein, et al., 2002; Goldberg, et al., 2008).

QuickSleeper 4

The QuickSleeper 4 (Dental Hi Tec) (Figures 11-15) is a motorized needle system that can perforate the cortical plate and administer the local anesthetic through that perforation in a single procedure, which greatly reduces the margin for errors experienced with Stabident and X-Tip systems. Nusstein (1998) and Rood (1981) found that intraosseous injections of lignocaine 1.100000 adrenaline were successful more than 90% of the time and after achieving complete pulpal anesthesia once a successful IANB injection is confirmed.

Maxillary molars

Maxillary molars

Onset is almost immediate, and duration has been reported to last approximately 45 minutes, which is more than adequate to access the pulpal space and complete biomechanical preparation. The big advantage of the QuickSleeper system is the single action of penetration, injection, and withdrawal; the efficiency and success of this procedure is invaluable in these cases.

Intraosseous ligamental pathway via PDL

My preference is a combination of intraligamental and intraosseous techniques facilitated by the QuickSleeper S4 (Dental Hi Tec) handpiece with the 16 mm motorized needle via the periodontal ligament in one continuous step.

The needle is placed in the gingival crevice, and the anesthetic is pumped slowly before activating the motor to rotate the needle in 5 second intervals, passing through the periodontal ligament into the cancellous bone around the apices where the anesthetic is deposited to where it is most needed. This route follows a natural pathway, offering the least resistance to penetrating the cancellous bone through the PDL and avoids the problems posed by root anatomy, root proximity, and cortical bone density.

The injection site can be adapted to the mesial, distal, furcation, or lingual aspects, depending on the most advantageous straightline approach for the needle determined by the tooth anatomy and position in the arch (Figure 14). This is administered routinely in acutely pulpitic mandibular cases in my practice, giving close to 100% results, enabling the endodontic procedure to be completed comfortably for both patient and operator.

Onset of anesthesia is almost immediate, and this avoids the shortcomings and difficulties of Stabident, which include locating the perforation holes, the bulkiness of the X-Tip technique in limited space, difficulty perforating thick cortical bone in posterior mandibular teeth, and avoiding the root anatomy (Figure 15). The optimal injection site in lower molars is dependent on the root anatomy with distal or furcation approach covering most situations.

Intraosseous injections with 2% lignocaine with 1:1000,000 adrenaline can result in a transient increase in heart rate in 70% of patients, and patients should be forewarned to expect this. They should also be reassured that this will pass and have the positive benefits highlighted to them to ensure acceptance and compliance (Stabile, et al., 2000).

Intrapulpal injection

Despite the apparent success of the IANB supplemented by periodontal ligament or intraosseous injection (more than 90% complete pulpal anesthesia), it is not uncommon for patients with acute long-standing pulpitis to experience some discomfort as pulp fibers can still spark, despite apparent total anesthesia present. In these cases, smooth turbine bur action can usually be tolerated until pulp chamber access is established. Anesthetic can then be injected under pressure, allowing further access. In these cases, a fine gauge needle can be inserted into the canal orifice and anesthetic again injected under pressure before instrumenting the individual canals. It is a dynamic situation and requires constant monitoring and communication.

A pinhead pulpal exposure can then be created and injected under pressure. Be committed and maintain constant communication, reassuring the patient that all is being done to get the desired result and facilitating biomechanical preparation (Birchfield, Rosenberg, 1975; VanGheluwe, Walton, 1997).

Summary

Achieving profound pulpal anesthesia is the cornerstone of successful endodontics, and this poses challenges in teeth with irreversible pulpitis, particularly mandibular molars. Failure has been attributed to poor technique or aberrant anatomy, while the reality is that the IANB is not fit for purpose in these situations, and supplemental techniques are required.

Intraligamental and intraosseous techniques are very successful in achieving profound pulpal anesthesia and should be considered as part of the routine approach. Stabident and X-Tip have been around for some time and are well proven. However, the QuickSleeper 4 motorized needle system, applied through the ligamental pathway, is a game changer, benefiting both the patient and operator through predictability and simplicity of use. It is an invaluable tool that should be a part of routine anesthetic protocol in acutely inflamed mandibular situations.

References

- Birchfield J, Rosenberg P. Role of the anesthetic solution in intrapulpal anesthesia. J Endod. 1975;1(1): 26-27.

- Claffey E, Reader A, Nusstein J, Beck M, Weaver J. Anesthetic efficacy of articaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2004;30(8):568-571.

- Cohen HP, Cha B,Y Spangberg LS. Endodontic anesthesia in mandibular molars: a clinical study. J Endod. 1993;19(7):370-373.

- de Jong RH. Neural blockade by local anesthetics. JAMA. 1977;238(13):1383-1385.

- Dreven LJ, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ, Weaver J. An evaluation of an electric pulp tester as a measure of analgesia in human vital teeth. J Endod. 1987;13(5):233-238.

- Goldberg S, Reader A, Drum M, Nusstein J, Beck M. Comparison of the anesthetic efficacy of the conventional inferior alveolar, Gow-Gates, and Vazirani-Akinosi techniques. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1306-1311.

- Gow-Gates GA. Mandibular conduction anesthesia: a new technique using extraoral landmarks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36(3):321-328.

- Hargreaves KM, Keiser K. Local anesthetic failure in endodontics: Mechanisms and Management. Endod Topics. 2002;1(1):26-39.

- Hargreaves KM. Neurochemical Factors in Injury and Inflammation in Orofacial Tissues. In: Lavigne GJ, Lund JP, Sessle BJ, Dubner R. eds. Orofacial Pain: From Basic Science to Clinical Management. Chicago: Quintessence Publications; 2001.

- Ianiro SR, Jeansonne BG, McNeal SF, Eleazer PD. The effect of preoperative acetaminophen or a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen on the success of inferior alveolar nerve block for teeth with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2007;33(1):11-14.

- Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett IP, Meechan JG. Articaine buccal infiltration enhances the effectiveness of lidocaine inferior alveolar nerve block. Int Endod J. 2009;42(3):238-246.

- Mikesell P, Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. A comparison of articaine and lidocaine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Endod. 2005;31(4):265-270.

- Nusstein J, Reader A, Beck FM. Anesthetic efficacy of different volumes of lidocaine with epinephrine for inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Gen Dent. 2002;50(4):372-375; quiz 376-377.

- Nusstein J, Claffey E, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. Anesthetic effectiveness of the supplemental intraligamentary injection, administered with a computer controlled local anesthetic delivery system, in patients with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2005;31(5):354-358.

- Nusstein J, Reader A, Nist R, Beck M, Meyers WJ. Anesthetic efficacy of the supplemental intraosseous injection of 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine in irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 1998;24(7):487-491.

- Parente SA, Anderson RW, Herman WW, Kimbrough WF, Weller RN (1998) Anesthetic efficacy of the supplemental intraosseous injection for teeth with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 1998;24(12):826-828.

- Parente SA, Anderson RW, Herman WW, Kimbrough WF, Weller RN. Anesthetic efficacy of the supplemental intraosseous injection for teeth with irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 1998;24(12):826-828.

- Reader A, Nusstein J. Local anesthesia for endodontic pain. Endod Topics. 2002;(3):14-30.

- Rood JP, Pateromichelakis S. Inflammation and peripheral nerve sensitisation. Br J Oral Surg. 1981;19(1): 67-72.

- Smith GN, Walton RE, Abbott BJ. Clinical evaluation of periodontal ligament anesthesia using a pressure syringe. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;107(6):953-956.

- Stabile P, Reader A, Gallatin E, Beck M, Weaver J (2000) Anesthetic efficacy and heart rate effects of the intraosseous injection of 1.5% etidocaine (1:200,000 epinephrine) after an inferior alveolar nerve block. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89(4):407-411.

- Strichartz GR. Molecular mechanisms of nerve block by local anesthesics. Anesthesiology. 1976;45(4):421-441.

- Vandermeulen E (2000) Pain perception, mechanisms of action of local anesthetics and possible causes of failure. Rev Belge Med Dent. 1984;55(1):29-40.

- VanGheluwe J, Walton R. Intrapulpal injection: Factors related to effectiveness. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83(1):38-40.

- Vreeland DL, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers W, Weaver J. An evaluation of volumes and concentrations of lidocaine in human inferior alveolar nerve block. J Endod. 1989;15(1):6-12.

- Wali M, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers W. Anesthetic efficacy of lidocaine and epinephrine in human inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Endod. 1988;14(4):193

- Walton RE, Abbott B. Periodontal ligament injection: a clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981;103(4): 571-575.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..