CE Expiration Date: March 10, 2025

CEU (Continuing Education Unit):2 Credit(s)

AGD Code: 157

Educational aims and objectives

This self-instructional course for dentists aims to present an overview of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) and their considerations for use in dental practice.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify key components of the PDMP.

- Outline steps to access the state’s PDMP.

- List reasons how utilizing the PDMP can protect dental

- List limitations to the PDMP.

- Complete a query utilizing the PDMP to evaluate a patient’s controlled substance record.

Nikki Sowards, PharmD; Michael O’Neil, PharmD; and Tyler Dougherty, PharmD; discuss how prescription drug monitoring programs play an important role in monitoring controlled substances

Introduction

Although not first-line therapy, prescription opioids play an important role in the management of acute dental pain. However, all medications carry risks, which in the case of opioids can lead to misuse, physiologic dependence, and diversion. Additionally, opioid use disorder may lead to overdose and death. According to the CDC, from 1999 to 2019, an estimated 247,000 deaths in the United States were attributed to overdoses involving prescription opioids.1 In dental practice, the majority of opioids prescribed are immediate-release formulations with a higher potential for misuse and diversion.2 Data also suggests that dentists prescribe more opioids than considered necessary for managing postprocedural acute pain.3 Over the past 10 years, many medical and dental boards as well as professional organizations have recommended or required routine use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs). The American Dental Association recommends dentists register and utilize their state’s PDMP to promote the safe and appropriate use of controlled substances.4 Currently, all 50 states have implemented a PDMP, and dental practitioners may access the following link for more information related to their state PDMP: https://www.pdmpassist.org/State.5,6 Dental practitioners must be fully knowledgeable of their own state’s PDMP. This article will serve as a primer and give a general overview for dental practitioners to optimize utilization of their state’s PDMP.

Use of the PDMP by dental practitioners

Historically, data has indicated that out of 805 members of the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network, only half of respondents reported having accessed a PDMP. Both lack of awareness and lack of knowledge regarding its use were the most common reasons cited for not using the database. Of those individuals who did report utilizing the PDMP, 33.5% indicated that their usage led them not to prescribe an opioid, while 25.5% reported usage led them to prescribe fewer opioid doses. Overall, the findings of this research did suggest that a majority of dentists do find the PDMP helpful in their decision-making regarding the prescribing of controlled substances. Many states now mandate prescribers access the PDMP prior to prescribing controlled substances in defined circumstances.4

PDMP basics

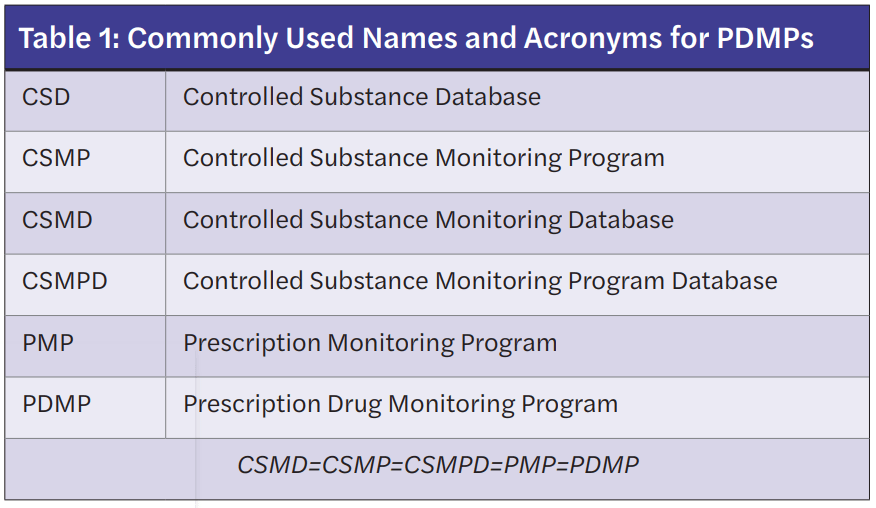

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) store outpatient controlled prescription medication information and are designed to track these prescriptions through an internet-accessed database maintained at the state level. Classes of controlled substances required to appear in the PDMP are determined by individual states. Of note, PDMPs are commonly referred to in a variety of ways depending on the state of origin. Table 1 lists commonly used terminologies that are equivalent to the PDMP.

The main components of the PDMP include tracking of a patient’s prescribed controlled prescriptions, prescriber tracking of prescriptions utilizing their DEA number, and surveillance/monitoring systems to detect trends and allow for statistical analysis. Controlled substances dispensed by community pharmacies and outpatient clinics are entered into the patient’s prescription record. When these prescriptions are dispensed, information associated with the prescription is uploaded to the PDMP at a time determined by the state with many pharmacies and clinics uploading at the immediate point-of-sale or dispensing.

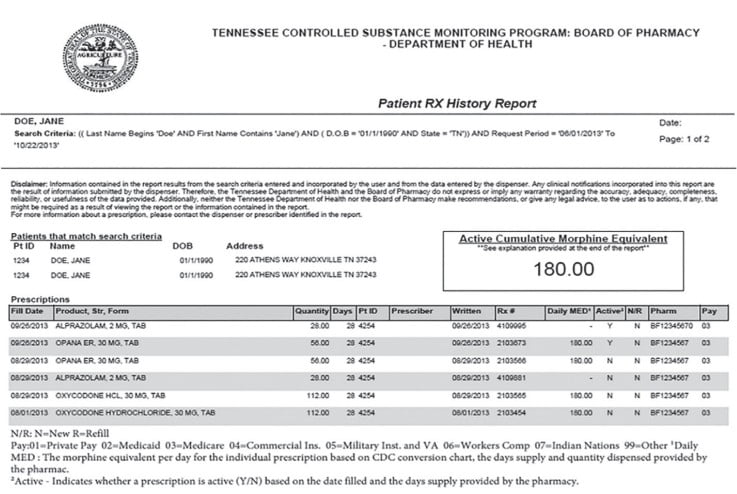

The PDMP report contains the patient’s name, date of birth, any addresses associated with that patient, and any prescriptions for controlled substances that have been dispensed by a pharmacy or outpatient clinic. Specific information typically available for each prescription follows:

- medication name

- medication strength

- quantity filled

- number of days’ supply

- the prescriber’s DEA number

- the date the prescription was written

- the prescription number

- the pharmacy that filled the prescription.

Some PDMPs are more advanced and may contain additional information such as total daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME), dispensed naloxone, and payment type.6,7 Figure 1 represents a typical report generated from the state of Tennessee PDMP. This database is maintained by the Tennessee Board of Pharmacy, which is a division of the State’s Public Health Department.8 It is critical for practitioners to recognize that information uploaded to the PDMP comes directly from pharmacies or outpatient clinic records. Medication information is entered into the pharmacy’s or clinic’s computers by a variety of personnel. None of this data is ever validated prior to being uploaded to the PDMP other than by personnel entering the data. Any entry errors by practitioners, pharmacists, technicians, or staff get uploaded to the database. Therefore, it is critical to recognize that the PDMP report is not evidence of a crime and should be used only as a starting point to verify potential concerns or “red flags” found in the report.

The PDMP ultimately serves to inform clinical practice and improve prescribing. When utilized in a timely manner, PDMPs can prevent dangerous combinations of medications, limit prescribing of unnecessary or duplicate prescriptions, and prevent doctor shopping as well as other types of medication diversion.

Accessing PDMPs

Accessing PDMPs requires the prescriber to register with the state organization responsible for managing the database. Like most internet-based restricted sites, passwords are initially assigned by the regulating body and can be changed to a more convenient password later by the user. The database should only be accessed to evaluate a specific provider’s patient records “near time” of the scheduled appointment unless the prescriber is investigating potential fraud or diversion. Information provided in the PDMP must be handled the same as other patient information, which requires following all requirements of The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).9 Accessing the PDMP to ascertain information about friends, families, other practitioners, or patients not part of the prescriber’s immediate practice is usually considered a violation of state and federal law that may result in prosecution. Prescribers are not usually obligated to provide patients with a copy of their PDMP report. However, if a copy of the report is placed in a patient’s medical record, the patient or insurance agencies may have access to the report. Additionally, caution should be used when placing the PDMP report in the chart since it potentially may contain another patient’s information depending on how the patient’s information was queried.

Access to the PDMP is restricted to prescribers, pharmacists, the DEA, and law enforcement entities executing a warrant or who are part of a defined drug task force. However, most states allow the PDMP registered user to grant access to PDMP records to a limited number of users in the practice. In most cases this requires the user to use the registrant’s password. Ultimately, the PDMP registrants are responsible for any queries by any allowed users that use their password even if it is not for legitimate purposes. When “allowed users” leave the practice, passwords must be changed immediately to prevent misuse of the database. Some states now identify “allowed users” through special registrations linked to the PDMP registrant or allow support staff to have their own login code.10 Many medical practices and pharmacies have a separate login to the state’s PDMP that is often utilized by everyone in the practice. It is key that every licensed user use his/her own login to access the PDMP. Multiple users put the practice and individual login owners at risks for violations made by individuals using the facility’s login information inappropriately.

Many patients live in areas that border multiple states, allowing patients to access practitioners and pharmacies in different states. Some states’ PDMPs provide a link to other nearby states’ PDMP. To date, there is not a single, nationally controlled PDMP that integrates all patient information for all 50 states.

Querying the PDMP

After logging into the PDMP, the patient’s name and date of birth must be entered. Ideally this information should come from a government-issued identification such as a driver’s license, but this sometimes is not possible. The patient’s proper name should be used. Nicknames or abbreviated names should be avoided. For example, a patient named “Michael O’Neil” should not be entered as “Mike O’Neil” or vice versa. To avoid missing records that may have been entered using an abbreviated name, a more advanced search can be easily performed by using only the first initial of the patient’s first name and his/her last name. Caution is warranted when this method is used since any person named “O’Neil” whose first name starts with the letter “M” and has the exact birthdate will appear in the results. Spellings and dates-of-birth must be exact; otherwise, they will not be found in the report. Dental practitioners should also be vigilant for the potential for multiple patients who have the same last name and date of birth. The timeline of the search is also required. For practitioners treating an active patient, searches generally only need to go back 6 months to 1 year because practitioners are making a real-time clinical decision. When investigating patients for potential fraud or diversion, longer time periods may be warranted. Although patient addresses can be entered, patients frequently move, and listing a specific address in the query may limit the findings in the report. Errors entered into patient profiles that end up in the PDMP usually requires a formal request to the PDMP managing agency to correct the misinformation. Simply changing the information in the patient profile will not change the information in the PDMP. Once the PDMP report has been generated for the designated patient and the defined timeline, select the most recent prescription listed, and track on the timeline any medications within the same medication class. Look for any potential “red flags.” Repeat this process for any additional medications.

Identifying and evaluating “red flags”

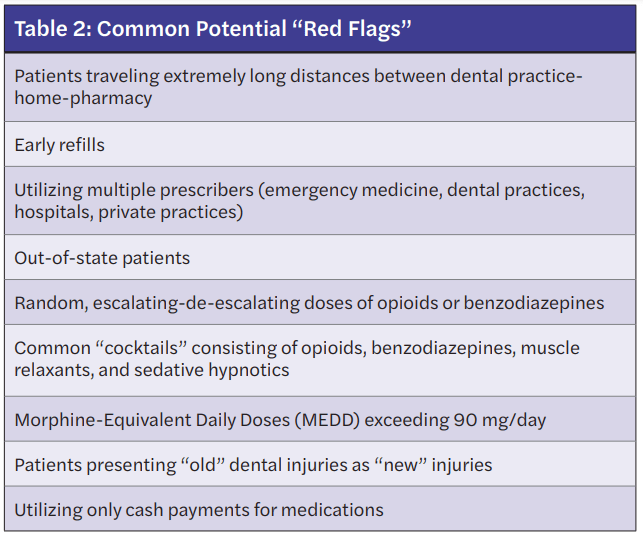

A “red flag” may be defined as any observation that provokes the user of the PDMP to evaluate the need, safety, or legitimacy of a prescribed medication. Identifying a “red flag” does not mean to immediately refuse to prescribe, but rather to ask questions and verify information before prescribing. Ultimately, refusing to prescribe often becomes a common action by the prescriber if controversial information is identified and verified.11

When reviewing the PDMP, general observations that may be identified as “red flags” include the following: early medication refills, duplicate medications, utilization of multiple pharmacies or multiple providers, extremely long distances traveled from a patient’s home-pharmacy-dental practice, persistent use of similar medications, including random escalating-de-escalating doses, variation in products, and concerning medication combinations, also commonly referred to as “cocktails.” Table 2 lists common “red flags” that may require further questioning.11,12

Limitations to the PDMP

Equally as important to the information provided in the PDMP is the information not found in the PDMP that potentially impacts prescribing. The PDMP report will not reflect any verbal changes that have been communicated to the patient such as increasing usage of a prescription. As previously mentioned, errors may occur when prescriptions are processed then uploaded to the database. Because Veterans Administration Medical Center patients receiving medical care are under federal regulation, prescriptions for controlled substances, including methadone and buprenorphine products, are not required to be reported to the PDMP. However, some Veterans Administration Medical Centers do voluntarily report to the PDMP. The PDMP does not usually contain patient diagnosis for the medications prescribed. Finally, all PDMPs are subject to the variety of connectivity issues that commonly occur with accessing information through an internet connection.

Reporting suspected diversion or fraud behavior

When suspicious findings in the PDMP have been confirmed to be attempts to divert controlled substances or commit fraud, most states require reporting to a specific drug enforcement agency. This may include the dental practitioner’s local police department, regional drug task force, or regional DEA office. The DEA requires the reporting of any suspicious activities surrounding controlled substances. Regardless, specific information including the time, date, patient’s name, address, date of birth, suspected illegal activity, medications indicated, and the verification process used to confirm the information in the PDMP should be reported. All information collected surrounding the suspected case should be documented in the patient’s medical record.13

Best practices

Recommendations to help optimize a dental practitioner’s use of the PDMP include:

- Logging in to the PDMP often to stay familiar with passwords and to stay current with any PDMP changes.

- Training staff to run the PDMP report and to have the report ready for review when your patients arrive.

- Maintain positive relations with local pharmacies and law enforcement since they are frequently the first to identify potential problems and can help protect your practice.

- Evaluate PDMP reports every 6 months with your office manager using your DEA registration number to identify fraudulent prescriptions that have been issued using your DEA number.

- Evaluate the PDMP for any brand new patient requiring a controlled substance.

Summary

In summary, PDMPs are an effective tool for detecting and deterring controlled substance fraud and diversion. Querying the PDMP requires exact name and date of birth. “Red flags” require further questioning and verification before prescribing or refusing to prescribe since information contained in the PDMP is not evidence of a crime. Sharing of PDMP login passwords should be limited. Although there are some limitations to PDMP, most information is accurate. Dental practitioners prescribing controlled substances should access the PDMP to stay familiar with their passwords and to be kept up-to-date on major changes to their state’s PDMP. Confirmed suspicions or fraud or diversion must be reported per state and federal laws.

References

- Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. http://wonder.cdc.gov. Accessed 1/7/22

- McCauley JL, Hyer JM, Ramakrishnan VR, et al. Dental opioid prescribing and multiple opioid prescriptions among dental patients: administrative data from the South Carolina prescription drug monitoring program. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(7):537-544.

- Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, et al. Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:328-334.

- McCauley JL, Gilbert GH, Cochran DL, et al. Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Use: National Dental PBRN Results. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019;4(2):178-186.

- Herion P, office GP, Marshall Cof J. Missouri becomes 50th state to introduce Prescription Drug Monitoring Database. KOMU 8. https://www.komu.com/news/state/missouri-becomes-50th-state-to-introduce-prescription-drug-monitoring-database/article_6e944f90-c7b8-11eb-a6ff-8742499b65dd.html. Published June 7, 2021. Accessed January 7, 2022.

- State PDMP Profiles and Contacts. https://www.pdmpassist.org/State. Accessed January 7, 2022.7. Appriss, Inc. – Tennessee state government – tn.gov. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/healthprofboards/csmd/TNDataCollectionManual.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2021.

- Image Courtesy Tennessee Department of Public Health.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/hipaa.html#:~:text=The%20Health%20Insurance%20Portability%20and,the%20patient’s%20consent%20or%20knowledge. Published September 14, 2018. Accessed January 7, 2022.

- FAQ’s. https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/health-professional-boards/csmd-board/csmd-board/faq.html. Accessed January 7, 2022.

- Prescription Medication Diversion: Detection and Deterrence. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2019;47(3):180-181.

- O’Neil M, Winbigler B, Sowards A. Detection and Deterrence of Substance Use Disorders and Drug Diversion in Dental Practice. In: The ADA Practical Guide to Substance Use Disorders and Safe Prescribing. 143-149; 2015:144-147.

- Suspicious orders report system (sors). https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/sors/index.html#:~:text=On%20October%2023%2C%202019%2C%20DEA,115%2D271). Accessed January 7, 2022.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..

Nikki Sowards, PharmD, earned her Doctor of Pharmacy degree in 2012 from the University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy in Memphis, Tennessee. She completed a PGY-1 Pharmacy Practice residency in Knoxville, Tennessee. Dr. Sowards joined South College School of Pharmacy as an Assistant Professor in 2013. In 2015, Dr. Sowards worked as a Director of Hospital Pharmacy in Knoxville, Tennessee. Dr. Sowards is currently an Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice at South College School of Pharmacy. She practices at Blount Memorial Hospital where she focuses on pharmacy operations and pharmacy management.

Nikki Sowards, PharmD, earned her Doctor of Pharmacy degree in 2012 from the University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy in Memphis, Tennessee. She completed a PGY-1 Pharmacy Practice residency in Knoxville, Tennessee. Dr. Sowards joined South College School of Pharmacy as an Assistant Professor in 2013. In 2015, Dr. Sowards worked as a Director of Hospital Pharmacy in Knoxville, Tennessee. Dr. Sowards is currently an Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice at South College School of Pharmacy. She practices at Blount Memorial Hospital where she focuses on pharmacy operations and pharmacy management. Michael O’Neil, PharmD, received his Doctor of Pharmacy from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Dr. O’Neil has extensive experience in pain management, substance misuse, and medication diversion. Dr. O’Neil was editor and lead author for the American Dental Association’s book titled The ADA Practical Guide to Substance Use Disorders and Safe Prescribing, published in 2015. Dr. O’Neil has served as a consultant for prescription drug misuse and diversion for several entities including the Federal Drug Enforcement Agency. He is currently Professor and Chair of Pharmacy Practice at South College School of Pharmacy in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Michael O’Neil, PharmD, received his Doctor of Pharmacy from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Dr. O’Neil has extensive experience in pain management, substance misuse, and medication diversion. Dr. O’Neil was editor and lead author for the American Dental Association’s book titled The ADA Practical Guide to Substance Use Disorders and Safe Prescribing, published in 2015. Dr. O’Neil has served as a consultant for prescription drug misuse and diversion for several entities including the Federal Drug Enforcement Agency. He is currently Professor and Chair of Pharmacy Practice at South College School of Pharmacy in Knoxville, Tennessee. Tyler Dougherty, BA, PharmD, BCACP, received his Bachelor of Arts degree in Biochemistry from Maryville College in 2011 and his Doctor of Pharmacy degree from the University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy in 2015. He completed a postgraduate residency at South College School of Pharmacy in 2016. Dr. Dougherty is a Clinical Community Pharmacist and Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice where he specializes in community pharmacy practice and teaches ethics and pharmacy law. Dr. Dougherty is an invited speaker for healthcare professionals teaching ethics and law with emphasis on medication management.

Tyler Dougherty, BA, PharmD, BCACP, received his Bachelor of Arts degree in Biochemistry from Maryville College in 2011 and his Doctor of Pharmacy degree from the University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy in 2015. He completed a postgraduate residency at South College School of Pharmacy in 2016. Dr. Dougherty is a Clinical Community Pharmacist and Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice where he specializes in community pharmacy practice and teaches ethics and pharmacy law. Dr. Dougherty is an invited speaker for healthcare professionals teaching ethics and law with emphasis on medication management.