Dr. Tony Druttman looks at the importance of magnification and illumination in the practice of endodontics

This article is part of a series that appears in 10 consecutive issues and is designed to offer practical advice on some of the most common challenges that we face in endodontics. The purpose is to make the practice of endodontics easier. Some of the information will give you a better understanding of what you are dealing with; some will make it easier to avoid pitfalls; some will show you how to improve the quality of your work; and some will advise what to do in difficult situations. Although each article covers a specific topic, they interrelate, and some of the questions that arise may be answered in other articles. By nature it cannot be comprehensive, otherwise it would be a textbook, but hopefully, it will give you valuable practical information.

This article is part of a series that appears in 10 consecutive issues and is designed to offer practical advice on some of the most common challenges that we face in endodontics. The purpose is to make the practice of endodontics easier. Some of the information will give you a better understanding of what you are dealing with; some will make it easier to avoid pitfalls; some will show you how to improve the quality of your work; and some will advise what to do in difficult situations. Although each article covers a specific topic, they interrelate, and some of the questions that arise may be answered in other articles. By nature it cannot be comprehensive, otherwise it would be a textbook, but hopefully, it will give you valuable practical information.

Available technology

One of the primary purposes of root canal treatment is the elimination of bacteria from the root canal system, which as I have described in the first article of this series, is often very complex (Figure 1). When I qualified just over 30 years ago, the practice of endodontics was very different. We relied on 20/20 vision and nothing else. Once the canal entrances had been identified, everything was done pretty much just by feel. Now with the technologies available to us, while the importance of tactile sense cannot be underestimated, it is possible to overcome obstacles that are visible right into the depth of the canals.

Magnification in dentistry starts with operating loupes, which will increase the image size from 2x to about 5x (Figure 2). After 5x, the loupes start to become very heavy, and magnification is better provided by the operating microscope, which magnifies the image from about 5x to 20x (Figure 3). Illumination with the loupes comes in the form of a headlight, which obviates the need for a separate operating light. As it is mounted on the loupe frame or a headband, no shadow is produced. The light source in the operating microscope is integral within the scope itself, so that light passes down the canal walls. In straight canals, the apex can be clearly seen, as well as isthmuses, fins, and secondary canals. Both have their advantages and disadvantages. Loupes are considerably more versatile, and many dental procedures can be carried out at these low magnifications. However one pair of loupes only give one magnification, so the tendency is to have just one pair. Over the years, I have progressed from 2x to 3.25x to 4.25x. There are many situations, particularly in endodontics, where the tooth needs to be seen in much greater detail, and while I do change the magnification from time to time, most of my work is done at 10x. The greater the magnification, the narrower the width of field, and the lower the depth of field. The better we can see what we are doing, the more control we have. The more control we have, the greater the chances are for a successful result. Not all endodontic procedures require the use of the microscope, but at the very least, it is useful for checking canal cleanliness prior to obturation.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

The microscope has proven itself to be an invaluable tool for confirming the presence of cracks both in the natural crowns of teeth and in the roots of teeth restored with post crowns. External root resorption can also be confirmed with careful examination of the gingival margins under magnification. The marginal fit of restorations and the presence of caries can also be checked (Figure 4).

Canal location

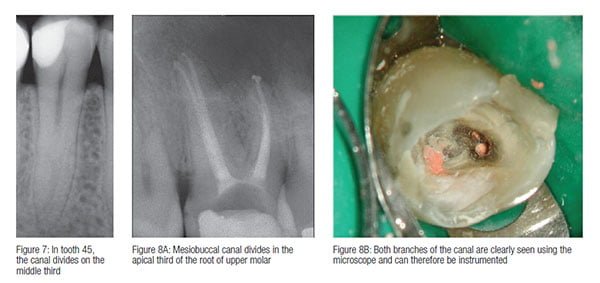

As discussed in last month’s article, finding the canals can be infinitely more difficult than cleaning and shaping them. The pulp chamber and even the canals themselves may be sclerosed. A very careful technique is required to preserve tooth structure, and this requires a good knowledge of canal anatomy, experience, and the use of the microscope. Second mesiobuccal canals in upper molars can often only be found at high magnification (Figure 5). Other teeth can sometimes have more than the expected number of canals (Figure 6), and failed endodontic treatment is often caused by missed canals. As I have discussed in previous articles in this series, a good quality preoperative radiograph will often indicate the presence of a canal that divides along its length (Figure 7), but the exact position can only be detected by careful visual examination under high magnification (Figures 8A and 8B). Similarly the presence of a second canal in the distal root, or a third canal in the mesial root of a lower molar, can only be detected by careful clinical examination.

Canal preparation

Because of the complexity of the root canal system, canal preparation cannot necessarily be considered to be complete just because a rotary instrument of a certain size and taper has been taken to a predetermined length, even with the accompanying irrigation regimes. The cross-sectional shape of canals may vary along their length. They may be circular at the apex and become oval more coronally, or have a teardrop shape. They may be joined to another canal or another branch via an isthmus, as is often the case with lower incisors and the distal canals of lower molars. C-shaped lower second molars can often present a considerable challenge in preparation. Only careful examination of the prepared canals using the microscope will identify (some of) those areas of the canal system that have remained unprepared. Seeing around a curve, however, is not an option with the microscope.

Endodontic retreatment

Endodontic retreatment

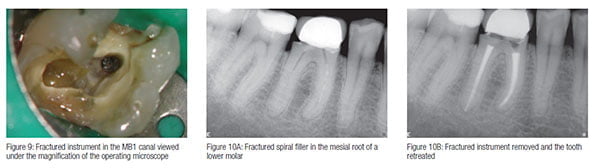

Another major area of endodontics where the microscope has proved its worth is in endodontic retreatment, both surgical and nonsurgical. The predominant cause of endodontic failure is due to the presence of bacteria, and retreatment involves removing obstructions that prevent access to the site of bacterial contamination. This may involve removing root-filling materials, or bypassing or removing ledges and blockages such as fractured instruments (Figure 9). I will be discussing retreatment in greater detail in the final article of this series. Instruments have been adapted and invented for use in conjunction with the microscope, particularly in the field of ultrasonics. Fractured instruments can often be removed using fine ultrasonic tips to trough around the instrument, removing minimal amounts of dentin (Figures 10A and 10B). This can only be done with the aid of the microscope. This has led to an increase in the success rates of nonsurgical retreatment approaching that of primary treatment. The success rate of surgical endodontics has also increased significantly with the use of microsurgical techniques. Soft tissue management, root end cavity preparation, and suturing techniques have all changed radically since the introduction of the microscope into surgical endodontics.

Ergonomics

Ergonomics

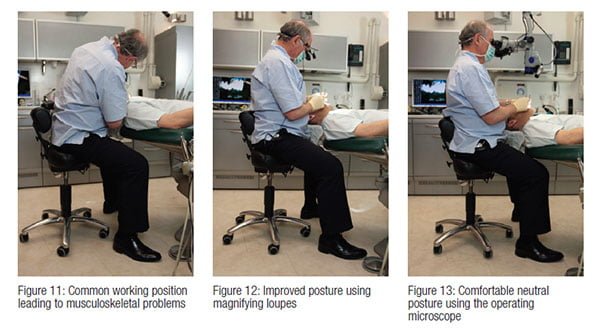

Another significant benefit from the use of both magnifying loupes and the operating microscope is in the field of ergonomics. The practice of dentistry over many years, especially endodontics, when the operator tends to sit in one position for a considerable length of time, can take its toll on the operator. Back, shoulder, and neck problems are not uncommon because of incorrect posture (Figure 11). By using an increased working distance, operating loupes allow the back to be held straighter than when working without magnification (Figure 12). The microscope allows for the neck, shoulders, and back to be in a comfortable neutral position, especially when used with an operating stool with arm supports (Figure 13).

In conclusion, the introduction of increased magnification and improved illumination of the operating field has many benefits, both for the operator and the patient, and nowhere more so than in endodontics. The ability to work with a high level of accuracy and control improves the quality of treatment, reduces treatment time, and reduces operator fatigue. I am convinced that the use of magnification should be an integral part of undergraduate teaching of operative dentistry, particularly in the field of endodontics.

Next issue: Determining length

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..

Tony Druttman, MSc, BChD, BSc, has extensive expertise in treating dental root canals, resolving difficult endodontic cases, and saving teeth from being extracted. His two London practices, one in the West End and the other in the City of London, are restricted to endodontic treatment. www.londonendo.co.uk

Tony Druttman, MSc, BChD, BSc, has extensive expertise in treating dental root canals, resolving difficult endodontic cases, and saving teeth from being extracted. His two London practices, one in the West End and the other in the City of London, are restricted to endodontic treatment. www.londonendo.co.uk