Dr. John West explains the importance of educating referring dentists about endodontic diagnosis and technique

The trouble is the endodontic clinician does not necessarily know what Anatomy Matters in advance of treatment. We, of course, do know that Anatomy Matters when lesions of endodontic origin (LEOs) develop or do not heal following an endodontic treatment to produce the endodontic seal. While failure to seal does not mean failure to heal (billions of endodontic treatments are short of the mark and have intact lamina dura, a healthy periodontal ligament, and are asymptomatic), failure to heal always means failure to seal.1 And your next patient’s precise significance of anatomy in preventing or curing LEOs is all quite unpredictable: one patient’s tooth might be fine with a weak endodontic obturation 5 mm short, at least at this point in time, while your patient has continued endodontic disease when you miss a lateral canal off a lateral canal!

Patients with underfilled portals of exit can be referred to the endodontist with a variety of underfilled endodontic seals: short fills, overextensions of underfilled canals, torn or stripped foramina, perforations, resorptions, ledges, missed canals, or broken file.2

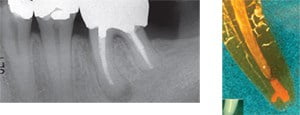

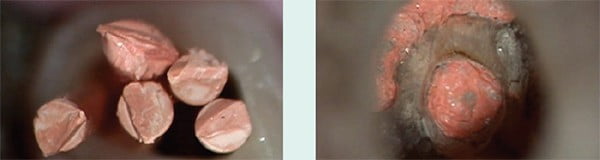

Unfortunately, much of the endodontics being taught today, while perhaps not intended, is being interpreted, understood, and accepted by the restorative dentist as “just purchase this magic instrument(s) and use this special ‘tool’ to ‘fill the canal,’ and it is easy and fast.” Often, the entire last few essential and critical millimeters of the root canal system do not quite make it into the sales conversation, and the result is that most endodontic referrals are for retreatments due to blocks, ledges, or transportations.3 Many referrals to the endodontist demonstrate unattended apical anatomy: 1) internal portal of exit transportation, 2) external portal of exit transportation, and 3) missed canal (Figure 1).

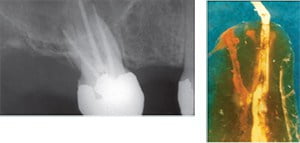

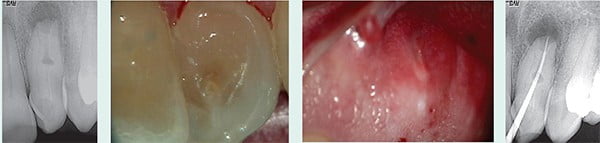

However, Anatomy Matters often do not just present to the endodontist as simply “the usual.” Often, Mother Nature throws us a curve in the form of particularly complex and/or unique anatomy as is the case with a patient with a dens in dente or dens invaginatus (tooth within a tooth).4 Joe was referred to me in 2000 for a sinus tract facial tracing to his maxillary left canine (Figure 2). The pulp tested non-vital, and the endodontic anatomy was carefully discovered and treated. A gutta-percha cone traced to the apical area of tooth No. 11. Although the CBCT imaging instrument was not available at that time, it most certainly would be helpful today. The pulpitic or non-vital dens in dente tooth is not a common referral to an endodontist, but our assignment remains the same, and that is to know all Anatomy potentially Matters all the time. The dens in dente tooth is an example that successful endodontic mechanics must be mastered by the endodontist for the “easy ones and the challenging ones” (Figure 3).

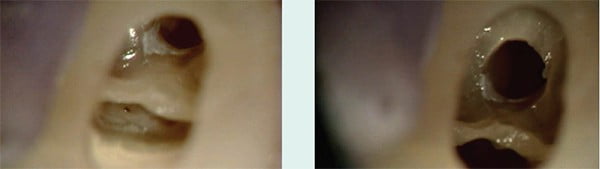

At his 13-year posttreatment, Joe’s LEO and sinus tract have healed, and he reports his tooth is comfortable. Dedicated and masterful endodontists want quality control; they want to measure long-term results, and set up office structures to validate healing over time. They know, “you don’t get what you want, you get what you measure” (Figure 4).

We have now referred Joe to an orthodontist for an orthodontic evaluation as tooth No. 11 is in misalignment, and he does not like the appearance of his front teeth due to the dens in dente shape and alignment. Improving his smile will have ultimately required an interdisciplinary team approach of endodontist, orthodontist, and restorative dentist.

As an endodontist, the success of the referring dentist is our priority. For those referring dentists who treat some or many of their endodontic patients, we can provide added value to their practice when we educate them about endodontic diagnosis and technique. Knowledge can be the difference that makes the difference to their endodontic outcomes. If you are currently having difficulty with busyness, here is something you can do to truly open a conversation about endodontic anatomy and endodontic predictability: download one or more of my previous and/or present five Anatomy Matters series, and show them what they may not know.6-9 You can mail hard copies, or better yet, teach them face-to-face. The articles should teach them to better understand the frequency of underfilled root canal systems and endodontic predictability. It should also teach them to slow down; design more successful and appropriate access cavities; irrigate properly and with the right irrigants to remove biofilm, pulp remnants, and smear layer; understand glidepath for safe mechanical endodontics; and appreciate that 3D obturation is a direct function of shape and obturation hydraulics during compaction regardless of technique. When you deliver knowledge to your referring dentists that will positively change their endodontic experience, you are delivering something that, to me, is priceless.

Anatomy Matters when it matters.

- West J. Endodontic update. J Esthetic Restorative Dent. 2006;18:280-300.

- West J. Perforations, blocks, ledges, and transportations: overcoming barriers to endodontic finishing. Dent Today. 2005;(1)243:68-73.

- West J. How do masters do it? Survey presented in lecture at the annual scientific session of the American Association of Endodontists, Boston, MA. April 2012.

- West J. Anatomy Matters. Endodontic Practice US. 2012;5(2):14-16.

- Lichota D. Endodontic treatment of a maxillary canine with type 3 dens invaginatus and large periapical lesion: a case report. J Endod. 2008;34(6).

- West J. Anatomy Matters. Endodontic Practice US. 2012;5(2):14-16.

- West J. Anatomy Matters—part 2. Endodontic Practice US. 2012;5(4):26-27.

- West J. Anatomy Matters—part 3. Furcal endodontic seal heals furcal lesion of endodontic origin. Endodontic Practice US. 2012;5(6):22-24.

- West J. Anatomy Matters—part 4. Long-term case report. Endodontic Practice US. 2012;6(1):50-51.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..

John West, DDS, MSD, the founder and director of the Center for Endodontics, continues to be recognized as one of the premier educators in clinical and interdisciplinary endodontics. Dr. West received his DDS from the University of Washington in 1971 where he is an affiliate associate professor. He then received his MSD in endodontics at Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine in 1975 where he is a clinical instructor and has been awarded the Distinguished Alumni Award. Dr. West has presented more than 400 days of continuing education in North America, South America, and Europe while maintaining a private practice in Tacoma, Washington. He co-authored “Obturation of the Radicular Space” with Dr. John Ingle in Ingle’s 1994 and 2002 editions of Endodontics and was senior author of “Cleaning and Shaping the Root Canal System” in Cohen and Burns 1994 and 1998 Pathways of the Pulp. He has authored “Endodontic Predictability” in Dr. Michael Cohen’s 2008 Quintessence text Interdisciplinary Treatment Planning: Principles, Design, Implementation, as well as Dr. Michael Cohen’s soon to be published Quintessence text Interdisciplinary Treatment Planning Volume II: Comprehensive Case Studies. Dr. West’s memberships include: 2009 president and fellow of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry, and 2010 president of the Academy of Microscope Enhanced Dentistry, the Northwest Network for Dental Excellence, and the International College of Dentists. He is a 2010 consultant for the ADA’s prestigious ADA Board of Trustees where he serves as a consultant to the ADA Council on Dental Practice. Dr. West further serves on the Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine’s Boston University Alumni Board. He is a Thought Leader for Kodak Digital Dental Systems, and serves on the editorial advisory boards for: The Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, Practical Procedures and Aesthetic Dentistry, and The Journal of Microscope Enhanced Dentistry. Visit

John West, DDS, MSD, the founder and director of the Center for Endodontics, continues to be recognized as one of the premier educators in clinical and interdisciplinary endodontics. Dr. West received his DDS from the University of Washington in 1971 where he is an affiliate associate professor. He then received his MSD in endodontics at Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine in 1975 where he is a clinical instructor and has been awarded the Distinguished Alumni Award. Dr. West has presented more than 400 days of continuing education in North America, South America, and Europe while maintaining a private practice in Tacoma, Washington. He co-authored “Obturation of the Radicular Space” with Dr. John Ingle in Ingle’s 1994 and 2002 editions of Endodontics and was senior author of “Cleaning and Shaping the Root Canal System” in Cohen and Burns 1994 and 1998 Pathways of the Pulp. He has authored “Endodontic Predictability” in Dr. Michael Cohen’s 2008 Quintessence text Interdisciplinary Treatment Planning: Principles, Design, Implementation, as well as Dr. Michael Cohen’s soon to be published Quintessence text Interdisciplinary Treatment Planning Volume II: Comprehensive Case Studies. Dr. West’s memberships include: 2009 president and fellow of the American Academy of Esthetic Dentistry, and 2010 president of the Academy of Microscope Enhanced Dentistry, the Northwest Network for Dental Excellence, and the International College of Dentists. He is a 2010 consultant for the ADA’s prestigious ADA Board of Trustees where he serves as a consultant to the ADA Council on Dental Practice. Dr. West further serves on the Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine’s Boston University Alumni Board. He is a Thought Leader for Kodak Digital Dental Systems, and serves on the editorial advisory boards for: The Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry, Practical Procedures and Aesthetic Dentistry, and The Journal of Microscope Enhanced Dentistry. Visit