Dr. Bruce H. Seidberg discusses three main factors that will reduce risk of legal issues

Risk management involves the development of a plan to monitor areas of a dental practice, including, but not limited to, the doctor-patient relationship (DPR), informed consent, and documentation, otherwise referred to as a “triad of concerns” to avoid perceived or potential problems in the practice of dentistry.1,2 Understanding the issues, communicating appropriately when entering into a doctor-patient relationship, following the concepts of informed consent and documentation and then properly applying them are the ways to prevent dental malpractice litigation. Those three areas are more likely than not to be abused or neglected but are generally governed by the standard of care of the profession and can be the source of allegations.

A combination of the economy and the conundrum of insurance has caused a type of stress on certain segments of the population that seek healthcare from doctors but have limited financial resources; some of these individuals might even believe there should be an entitlement plan. The dental profession is one of the healthcare professions where individuals with limited finances might feel there exists an entitlement program for treatment, and they are usually the ones who ultimately seek redress from a perceived mistreatment. It appears that some patients are more brazen with remarks and display attitudes to dentists that they would not make to their physicians. Real-life situations have created an environment where practitioners must practice intelligently, with integrity,3 and at the same time, defensively.4 It would be surreal to believe that anyone could predict the type of patient who will file a malpractice lawsuit.3,5 Every patient is a potential plaintiff. Managing risk in dental offices offers a way to improve the profession, private practices, and protect dental licenses before, instead of after, attorneys and juries get involved and impose legal precedents — hence, the “triad of concerns” and a patient’s perceived ideas that misconduct occurred.

Professional liability includes the risks of claims being brought against a practitioner. Malpractice embraces all liability-producing conduct arising from the providing of professional services and is a special kind of negligence arising out of the doctor-patient relationship. Negligence is an unreasonable act or omission by a dentist in which the treatment provided falls below the accepted standard of care and results in a perceived patient harm. The basic legal concepts that prevail for malpractice and negligence are that of duty, breach of duty, proximate cause, and damages. The basic concepts have to be proven in the case of a malpractice claim, but not that of negligence. The only proven issue in negligence is whether the dentist acted reasonably under the circumstances. A dentist might not be negligent if he/she exercises such reasonable care and ordinary skill even though he/she mistakes a diagnosis, makes an error in judgment, or fails to appreciate the seriousness of the patient’s problem.7

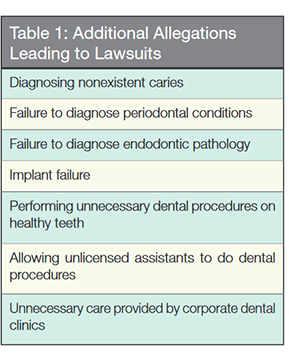

Legal allegations that dentists are at risk include, but are not limited to, crowns, bridges, and dentures done negligently or having an unsatisfactory result; failure to treat or improperly treat endodontic pathology; failure to diagnose or treat periodontal disease; implant failure; problematic extractions or removal of the wrong tooth; paresthesia of tissues; Medicaid fraud; and performing unnecessary dental treatment procedures on healthy teeth (Table 1).

Legal allegations that dentists are at risk include, but are not limited to, crowns, bridges, and dentures done negligently or having an unsatisfactory result; failure to treat or improperly treat endodontic pathology; failure to diagnose or treat periodontal disease; implant failure; problematic extractions or removal of the wrong tooth; paresthesia of tissues; Medicaid fraud; and performing unnecessary dental treatment procedures on healthy teeth (Table 1).

Causes of Action claims that are usually covered by insurance are those of negligence, lack of informed consent, breach of contract, and wrongful death. Claims of deliberate, intentional harm or those arising from the negligence of a third party are usually not covered. Although the law does not obligate the dentist to maintain a malpractice insurance policy, it is recommended that an adequate amount should be maintained to protect one’s dental license, professional practice, and personal assets.

The accepted definition of the standard of care is: that of reasonable care and diligence ordinarily exercised by similar members of the profession in similar cases in like conditions given due regard for the state of the art.8 National standards have replaced locality rules because of the ease of obtaining continuing education from local or national seminars or from the dental literature. The standards are usually set by the expert witnesses who are the most convincing to the jury or judge and are convincing when citing a specialty organization’s guidelines as a basis for their evidence for the specific case for which they are testifying. The ethical concepts of the standard of care are beneficence: to recommend the best therapy while minimizing potential harm, to avoid placing a patient at an unreasonable risk of harm, and one that cannot be disputed in court by an opposing expert witness. Evidence provided may include elements of locality, availability of facilities, specialization or general practice, proximity of specialists, and special facilities as well as other relevant considerations. Generalists are usually held to the same standard of care as those of specialists when performing that particular phase of dentistry.9,10 When one holds himself/herself out as a specialist as in the case of Simpson v. Davis or undertakes to perform procedures normally requiring the expertise of a specialist, he/she may be held to the professional standards of that specialty even though he/she may not have been certified in the specialty in question.11

The accepted definition of the standard of care is: that of reasonable care and diligence ordinarily exercised by similar members of the profession in similar cases in like conditions given due regard for the state of the art.8 National standards have replaced locality rules because of the ease of obtaining continuing education from local or national seminars or from the dental literature. The standards are usually set by the expert witnesses who are the most convincing to the jury or judge and are convincing when citing a specialty organization’s guidelines as a basis for their evidence for the specific case for which they are testifying. The ethical concepts of the standard of care are beneficence: to recommend the best therapy while minimizing potential harm, to avoid placing a patient at an unreasonable risk of harm, and one that cannot be disputed in court by an opposing expert witness. Evidence provided may include elements of locality, availability of facilities, specialization or general practice, proximity of specialists, and special facilities as well as other relevant considerations. Generalists are usually held to the same standard of care as those of specialists when performing that particular phase of dentistry.9,10 When one holds himself/herself out as a specialist as in the case of Simpson v. Davis or undertakes to perform procedures normally requiring the expertise of a specialist, he/she may be held to the professional standards of that specialty even though he/she may not have been certified in the specialty in question.11

The doctor–patient relationship (DPR) has been theorized to begin when the patient enters an office and completes the office documents requesting personal information, and they are reviewed by the dentist. The DPR actually begins when either the dentist gives dental advice with or without monetary consideration or enters the mouth to do an examination and offers advice.1,9 It is when the dentist agrees to provide a service or give an opinion on which the patient relies.12,13 The relationship is strengthened or weakened by the skills of communication. What is said and how it is said will set the stage for a patient’s opinions and acceptance. The DPR is adversely affected by perceptions of visual staff discontent and office ambiance. Practitioners must refrain from any and all sexual innuendos,14 which are another source of allegations. A patient cannot be terminated until commenced treatment has been completed. Once the relationship has started, it cannot end until both parties agree to end it, or if the dentist unilaterally decides to end it by following the appropriate methods of termination, or either party dies.

The principles of documentation and informed consent are recognized worldwide. Very little has changed since the inception of the informed consent concept and current day practice, but documentation concepts have. The intensity and importance of each subject has recently been brought to the forefront by inadequate presentations to patients and poor documentation of findings and events.

A patient who is properly informed is less likely to launch subsequent litigation over undisclosed risks that manifest. A health provider who has proper documentation memorializing the informed consent discussion and what was done is less likely to be involved in a lawsuit.

Informed consent is a fundamental tenet of the U.S. healthcare system, rooted in the ethical principles of respect for the patient autonomy and enhanced patient well-being. It is the ongoing dialogue between the patient and dentist in which both parties exchange information, ask questions, and come to an agreement on the course of a specific treatment. An individual’s right to self-determination was expressed and preserved in the case of Schloendorff v. Society of NY Hospital when Justice Cardozo in 1914 stated that “every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.”15 One of the first cases to label the lack of informed consent as “professional negligence” instead of “battery” was the case of Nathanson v. Kline16 in which the fundamental distinction was made between assault and battery, which constituted an intentional act, whereas negligence or malpractice was an unintentional act.

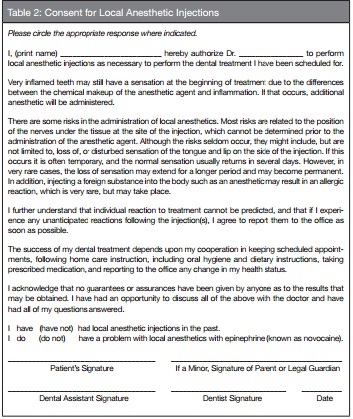

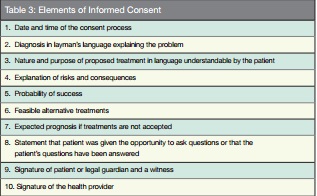

While the standard of care does not require a signed document for informed consent, any good lawyer will agree that an oral contract is only as good as the paper it is written on.17 Dentists are required by law to obtain consent from patients for any non-emergent treatment or diagnostic procedure, including consent for local anesthesia (Table 2). In an emergency situation, there may not be the opportunity to engage in a discussion, but action will be governed by what a reasonable person in similar circumstances would have consented to.18 It is the conversation a dentist has with a patient prior to treatment in which options and possible risks of the proposed treatment are explained and discussed. It is a conversation that cannot be delegated to auxiliary staff or another non-treating dentist. Shelton clarified non-delegation by emphatically stating, “He who cuts (treats) must inform; he who prescribes must also inform.”19 It is the information for a procedure for which a reasonable person would expect to receive about impending treatment. Informed consent is imperative for invasive procedures and those with established foreseeable risks. The discussion must be in understandable terms; and reasons for the procedure, benefits of the procedure, alternatives and consequences of the alternatives, including no treatment at all and the risks associated with the procedure, are discussed20 (Table 3). The standard of disclosure of all material risks originated from the landmark decision of Canterbury v. Spence21 in which the doctrine of informed consent stated that a doctor has a duty to disclose all reasonable information about a proposed treatment to his/her patients, including the benefits, risks of doing it or not, and the alternatives. The concept of informed consent was refined and established as a new standard for information disclosure.

Keep the discussion calm and relaxed, and give the patient time to ask questions and receive answers. Following the discussion, the dentist must determine whether or not the patient understood all of the information provided and then obtain a clear expression of the patient’s desire to proceed with the proposed treatment. Treatment performed in the absence of a valid consent may constitute battery16,22 and be actionable.

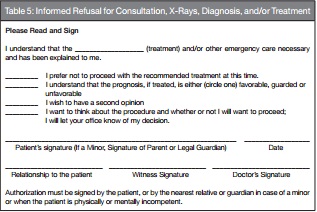

Informed consent is the discussion and not the form (Table 4). The consent form should be designed for the specific procedure and individual treatment plan. It is the document that will provide evidence and memorialize that the informed consent discussion took place. It should be of a general description, rather than specific, to allow for interpretation. If uncertain how specific the form should be, use the legal phrase “the treatment will include, but not be limited to A, B, or C.” After concluding the necessary information for the patient to make an informed consent, patients are given the customized document to sign, acknowledging that the conversation with the dental provider regarding the risks and benefits of treatment or no treatment and the alternatives were discussed and agrees or refuses the recommended treatment. Document the informed consent in the progress notes, dating and initialing it.20 Only those above the age of majority are allowed by law to give consent. The exception is if the minor is married or pregnant. A spouse cannot give consent for another spouse unless the spouse is mentally impaired. Only a parent or legal guardian can give consent for a minor: or in the case of a mentally impaired patient, the legally appointed guardian or court can give consent in the absence of a parent. An adolescent cannot give consent for an adult. The document becomes a permanent part of the patient’s chart. A patient can reject care or treatment deemed necessary and should then sign a substitute document of a “refusal for treatment” form (Table 5).  Informed consent allegations can be avoided (Table 6). If undisclosed risks materialize resulting in injury to the patient, and the patient can prove that he/she would not have consented to the treatment had the risk been disclosed, the chance for legal action increases.23

Informed consent allegations can be avoided (Table 6). If undisclosed risks materialize resulting in injury to the patient, and the patient can prove that he/she would not have consented to the treatment had the risk been disclosed, the chance for legal action increases.23

Dental records serve two major purposes.24,25,26 They are business records that tell a story about a patient’s dental health and treatment.

Dental records serve two major purposes.24,25,26 They are business records that tell a story about a patient’s dental health and treatment. They are also legal records, of which the accuracy would essentially be relied upon to help exonerate a practitioner from allegations of wrongdoing. Failing to maintain a written record that accurately reflects the evaluation and treatment of each patient can be construed as unprofessional conduct in many jurisdictions. Moreover, it reflects poorly on the practitioner and office when reviewed by either a patient, an investigator from the state licensing bureau, a plaintiff’s attorney, a judge, or a jury. In- accurate or incomplete records could imply an uncaring and unprofessional provider, which becomes a foundation of suspect in cases of allegations.

They are also legal records, of which the accuracy would essentially be relied upon to help exonerate a practitioner from allegations of wrongdoing. Failing to maintain a written record that accurately reflects the evaluation and treatment of each patient can be construed as unprofessional conduct in many jurisdictions. Moreover, it reflects poorly on the practitioner and office when reviewed by either a patient, an investigator from the state licensing bureau, a plaintiff’s attorney, a judge, or a jury. In- accurate or incomplete records could imply an uncaring and unprofessional provider, which becomes a foundation of suspect in cases of allegations.

Thorough documentation is the best legal defense a dentist can have against malpractice litigation, even better than a good expert witness. Every member of the dental team is equally responsible for recording pertinent facts about a patient’s visit. Most jurors have never seen a dental chart but rely on the information within it, if they can read it. Juries usually believe what is charted and conversely wonder why something significant was not charted. It is generally believed what is not written has not been done. A good patient record must be accurate, complete, and authentic. Maintaining complete and accurate records (“charts”) is a sign of quality care and an integral part of our duty to record the care of the patients. We live in a litigious society, and all healthcare professionals face the very real risk of being the target of a malpractice claim. As such, our profession must implement procedures to minimize the risk of such actions.

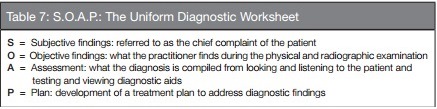

The universally accepted documentation format is that of S.O.A.P.24 (Table 7) and is outlined in a diagnostic worksheet format. “S” describes the subjective findings or the chief complaint the patient states as the reason for their concern. “O” describes the objective findings, or what is diagnosed using clinical testing combined with radiographic findings and any other aids used to make a definitive diagnosis. “A” describes assessment or the sum result of the diagnostic findings, and “P” describes the plan for treatment recommendations. The worksheet becomes part of the complete record so all entries must accurately reflect why the patient is seeking treatment and what the findings are.

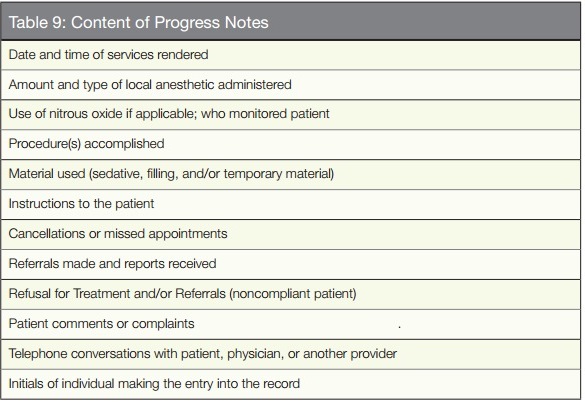

A proper recordkeeping system insures that you always record the required information consistently, using the same type of form for every patient for every visit. It infers a careful practitioner and enables one to follow the needs of a patient from visit to visit. Patient records are specifically used to record patient information that includes the evaluation, the treatment, and any patient reactions or concerns. They are not used for billing purposes; therefore, fee charges and payments are to be kept in a separate filing.

Records are to be organized and legible to tell the patient’s story to the third party reviewing it. Illegible records can imply a careless practitioner and sloppiness; entries should be clear and unambiguous. Only the facts of what is seen and done should be recorded in ink and dated, and the person who makes the entries should initial it. There should be no erasures, white-outs, or blackouts. Corrective entries are made by placing one line through the error and inserting the dated and initialed correction. All missed and cancelled appointments and failure to comply with instructions should be recorded, but derogatory comments and descriptive symbols that can be interpreted as derogatory should be left out. Referrals made and referrals refused or noncompliant patients must be recorded.

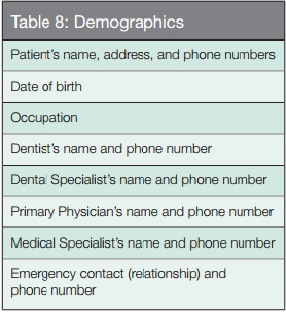

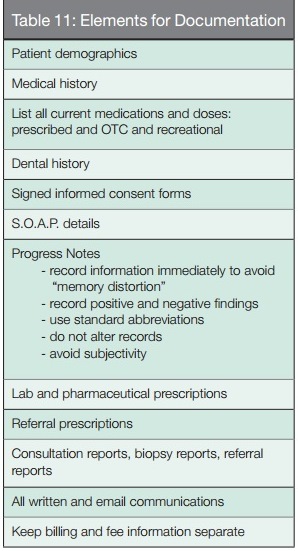

The basic elements of a complete record must include, but are not limited to, those items listed in Tables 8-11, such as demographics, medical and dental history, consent forms, progress notes, recommended guidelines, and other elements. Details for the contents of these charts can be found in the references cited.1,2,3,8,14,20,24 Going paperless using electronic records is allowable. However, the electronic system must have a “locking” system to prevent alteration within a reasonable period of time, and all details that would appear in paper records must be included electronically. There will be a time in the near future when all records will be required to be electronic, rendering offices paperless. Front desk software will have to be able to convert to the world of electronics and be compatible with e-scribe and drug programs.

The basic elements of a complete record must include, but are not limited to, those items listed in Tables 8-11, such as demographics, medical and dental history, consent forms, progress notes, recommended guidelines, and other elements. Details for the contents of these charts can be found in the references cited.1,2,3,8,14,20,24 Going paperless using electronic records is allowable. However, the electronic system must have a “locking” system to prevent alteration within a reasonable period of time, and all details that would appear in paper records must be included electronically. There will be a time in the near future when all records will be required to be electronic, rendering offices paperless. Front desk software will have to be able to convert to the world of electronics and be compatible with e-scribe and drug programs.

Requests for records by third parties or by the patient must be responded to within a reasonable time period of no more than 10 days. All requests honored should be in writing. The last dated entry in the progress notes should state who and why the record was transferred to, and the authorization for the request must be kept in the record. Only copies of the record and/or radiographs should be given to the requestor, never the original. Each state determines the fixed rate that can be charged for the reproduction of records. In New York state, it is 75 cents plus a “reasonable” fee for duplicating radiographs and models.

Requests for records by third parties or by the patient must be responded to within a reasonable time period of no more than 10 days. All requests honored should be in writing. The last dated entry in the progress notes should state who and why the record was transferred to, and the authorization for the request must be kept in the record. Only copies of the record and/or radiographs should be given to the requestor, never the original. Each state determines the fixed rate that can be charged for the reproduction of records. In New York state, it is 75 cents plus a “reasonable” fee for duplicating radiographs and models.

To further decrease risk, dentists must have the desire to obtain the knowledge and the skills to provide dental services27 and then follow the Fallon Three “A’s” Doctrine28 for success: Affability (be easy to speak to; approachable and gentle), Availability (be accessible to patients in need), and Ability (be able to think and accomplish the task and do it well), in that order. Ethics3 and risk management go hand in hand to render the best care possible to the patient.

Ethics3,8 is the byproduct of providing safe and effective care29 while a solid risk management program protects the practitioner. To avoid legal allegations and lawsuits, dentists must practice within the standard of care, communicate properly, inform patients, and legibly document everything (Table 12).

REFERENCES

1. Seidberg BH. Chapter 14. In: American College of Legal Medicine. Legal Medicine; Legal Aspects of Dentistry. 5th ed. Chicago, IL: Harcourt Publishers; 2001.

2. Seidberg BH. Chapter 50. In: American College of Legal Medicine. Legal Medicine; Legal Aspects of Dentistry. 6th ed. Chicago, IL: Harcourt Publishers; 2004.

3. Seidberg BH. Ethics, morals and law in the professional office. Endodontic Practice US., 2014;7(2):57-59.

4. Stimson PG, George LA. How to practice defensive dentistry. J Gt Houst Dent Soc. 1990;61(8):11-13.

5. Toner JJ. Malpractice. What They Don’t Teach You in Dental School. Tulsa, OK: PennWell Books; 1996.

6. King JH. The Law of Medical Malpractice in a Nutshell; St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1986: 3.

7. King JH. The Law of Medical Malpractice in a Nutshell; St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1986: 71.

8. Seidberg BH. Chapter 3. In: Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner JC, eds. Ingle’s Endodontics, Ethics, Morals and the Law in Endodontics.6th ed. 2008.

9. Graskemper JP. Professional Responsibility in Dentistry – a Practical Guide to Law and Ethics. Indianapolis, IN; Wiley-Blackwell: 2011.

10. Kimmel S. Standards of Care in Dentistry. Suwanee, GA; Harrison Company Publishers: 1999.

11. Simpson v Davis, 219 Kan. 584, 549 P.2d 950 (1976).

12. Seidberg BH. Chapter 50. In: American College of Legal Medicine. Legal Medicine; Legal Aspects of Dentistry. 7th ed. Chicago, IL: Harcourt Publishers; 2007.

13. Seidberg, B.H.: in Study Syllabus, American College of Legal Medicine; Dental Malpractice chapter, 2003

14. Seidberg BH. Harassment – Crossing the Professional Line; Endodontic Practice US. 2013;6(5):42-45.

15. Schloendorff v Society of NY Hosp, 211 NY 125, 129, 105 N.E. 92, 93 (1914).

16. Nathanson v Kline, 186 Kan 393, 350 P.2d 1093 (1960).

17. Eastern Dentists Insurance Co. Malpractice Insurance Company: The Value of Informed Consent – An EDIC Case Study, November 2014

18. Ibid: EDIC; 2014

19. Shelton, P. American Board of Legal Medicine, Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA; February 2012.

20. Seidberg BH. Understanding the legal concept of informed consent; The Bulletin, New York State Fifth District Dental Society, v56#2, 2011

21. Canterbury v Spence, 464 F.2d 772, 783 (D.C.Cir. 1972), cert. Denied, 409 U.S. 1064 (1974).

22. Shuler v Garrett, 743 F.3d 170 (8th Cir. 2014).

23. Seidberg BH. American Board of Legal Medicine, Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA; February 2012.

24. Seidberg BH. Record keeping in dentistry. Nevada Dental Journal. Winter 2010.

25. Oberbreckling, PJ. The components of quality dental records. Dent Econ. 1993;83(5):29-30, 32, 34.

26. Scott RW. Legal Aspects of Documenting Patient Care. Sudbury, M: Aspen Publishers, Inc; 1994.

27. Schilder H. Class notes. Boston, MA: Boston University School of Graduate Dentistry; 1966.

28. Fallon M. Personal communication. 2000.

29. Udey D. Within your control – ethics in dentistry. On the Cusp. 2014;18.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..