Drs. Avi Shemesh and colleagues’ study assessed certain diagnoses and treatment plan formulations and how they differed among clinicians using teledentistry.

Drs. Avi Shemesh, Marina Korektor-Rubinstein, Iddo Levy, Aurel Dadoun, Roman Grushyn, Alin Yaya, Shir Keshales-Shultz, Meital Abadi, and Avi Levin look into how to improve teledentistry outcomes

Drs. Avi Shemesh, Marina Korektor-Rubinstein, Iddo Levy, Aurel Dadoun, Roman Grushyn, Alin Yaya, Shir Keshales-Shultz, Meital Abadi, and Avi Levin look into how to improve teledentistry outcomes

Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of the present study was to assess pulp and root canal diagnoses and treatment plan formulations performed by endodontic specialists (ES) and general practitioners (GP) in the clinic and by teledentistry.

Materials and methods

The study included 187 patients who required endodontic specialist (ES) consultation. The study consisted of three phases: General practitioners (GP) in the clinic (GPIC), ES by teledentistry (EST), and ES in the clinic (ESIC). In each phase, pulp and periapical diagnoses and treatment plans were determined. The results were summarized, and differences among the three examination methods were evaluated. Data was analyzed in SPSS-24 using the Chi-square test. The p-value was set at 0.05.

Results

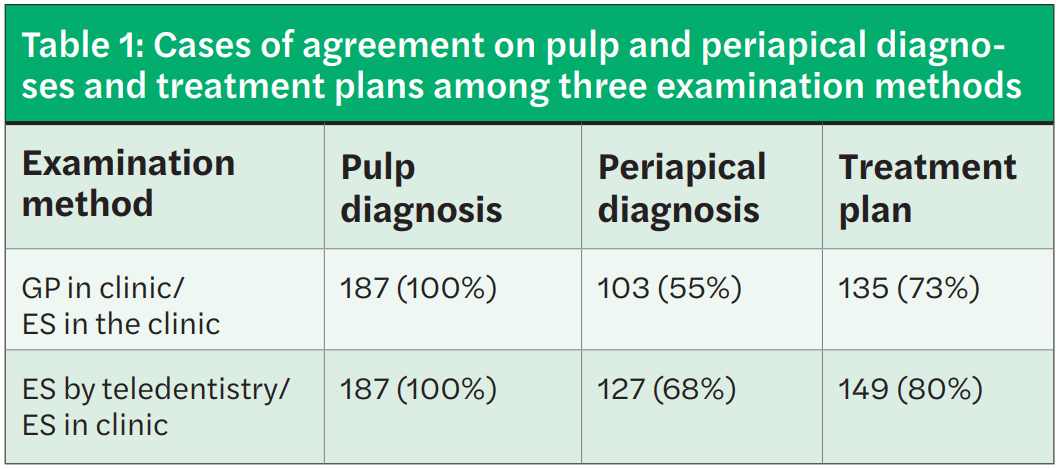

Complete agreement on pulp evaluations was found between ESIC and GPIC and between ESIC and EST. Partial agreement on periapical diagnoses and treatment plans was found (an agreement of 55% on periapical diagnoses and 73% on treatment plans determined by GPIC and ESIC and an agreement of 68% on periapical diagnoses and 80% on treatment plans determined by EST and ESIC).

Conclusions

Continuing education for GPs will lead to better and more successful teledentistry, as it could reduce the number of referrals to specialists, reduce the waiting time for appointments, and minimalize the in-person interaction between patients and dentists/dental clinic staff, which is crucial during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

As life expectancy increases and with advances in medical system technology and procedures, burdens on the healthcare system increase as well. Telemedicine is a broad term comprising a number of technologies, from digital X-rays to over-the-phone consultations, videoconferencing, and remote surgery.1 In other words, telemedicine is simply the use of telecommunications technology to deliver medical care or services, thereby making medical care more accessible, convenient, and affordable. Telemedicine makes it easier for patients and individuals to access medical care. Rather than spending many hours or days traveling to a healthcare center, medical advice and consultation can be obtained more locally, freeing up time and increasing the ease of receiving care.2

Teledentistry is a term that combines the terms telecommunications and dentistry. It involves the delivery of clinical data and images through different technologies for dental consultation and treatment plan formulation at a distance.3 The term “teledentistry” was first used in 1997, when Cook defined it as “… the practice of using videoconferencing technologies to diagnose and provide advice about treatment over a distance.”4

In 1994, telemedicine was first used as a subspecialist field in a military project of the United States Army (U.S. Army’s Total Dental Access Project), aiming to improve patient care and dental education and to effectuate communication among dentists, dental laboratories, and dental specialists. Teleconsultation through teledentistry can take place by either “real-time consultation” or the “store-and-forward method.”5 Real-time consultation involves a videoconference in which dental specialists and their patients communicate with one another from different locations. The store-and-forward method involves the exchange of clinical information, static images, and radiographical data collected and stored by dental general practitioners, who forward them to dental specialists, who determine consultation and treatment plans.3,6

Learning objectives

The purpose of the present study was to compare pulp and periapical diagnosis and treatment plan formulation by endodontists and general practitioners performed in the clinic and by teledentistry and to evaluate the efficacy and accuracy of teledentistry.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on October 18, 2018 (number of approval–5269). The study included teeth from 187 patients from military bases (average age of 19 years old) who required endodontic specialist (ES) consultation.

All patients with teeth with existing root canal treatment who were referred for endodontic consultation to decide whether endodontic involvement was necessary were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients who were referred for endodontic consultation for other purposes were excluded from the study.

The study included three phases of examination for each patient:

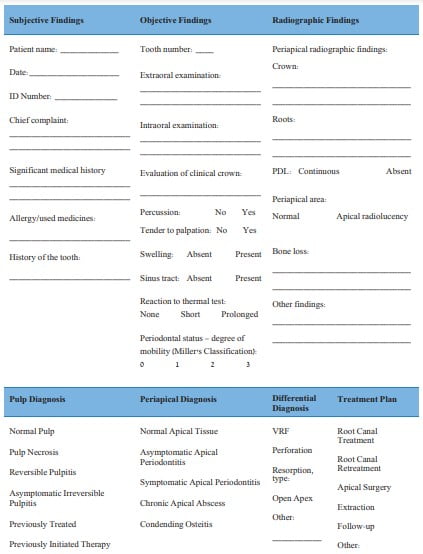

First phase — examination by a GP in the clinic (GPIC): The GPIC phase included pulp and periapical diagnosis and treatment plan formulation performed by a GP via clinical and radiographical examination in the clinic according to a structured questionnaire (Figure 1).

Second phase — teledentistry “store-and-forward method” by an ES (EST): The EST phase included pulp and periapical diagnosis and treatment plan formulation performed by an ES using the periapical radiograph and questionnaire findings from the first phase, which were sent electronically from a GP.

Third phase — examination by an ES in clinic (ESIC): The ESIC phase involved pulp and periapical diagnosis and treatment plan formulation performed by an ES via clinical and radiographic examination in the clinic. The third phase was performed 2 weeks or more after the second phase by the same endodontist.

A total of four general practitioners with 3-4 years’ experience and two endodontic specialists with 5 years’ experience participated in the study. The diagnoses and treatment plans in each phase were summarized, and disagreements among the three examination phases were evaluated.

Data was analyzed using SPSS-24 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). In order to examine the existence of variance between the groups, a chi-square tests were used. The p-value was set at 0.05.

Expected outcomes

We expected agreement between the ESIC and EST groups in both pulpal and periapical diagnoses and suggested the highest rate of differences in diagnoses will be found in comparing ESIC and GPIC groups due to variations in examination technique and lack of clinical experience.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the agreement on pulp and periapical diagnoses and treatment plans among the three examination methods. Complete agreement on pulp diagnoses was found between ESIC and GPIC and between ESIC and EST, while partial agreement on periapical diagnoses and treatment plans was observed (Table 1).

GP in the clinic compared to ES in the clinic

- Among 84 (45%) cases of disagreement on periapical diagnoses, most cases (70%) of disagreement were due to incorrect estimation of symptoms (Table 2).

- Among 52 (27%) cases of disagreement on treatment plans, most cases (83%) of disagreement were about the necessity of endodontic involvement (Table 3).

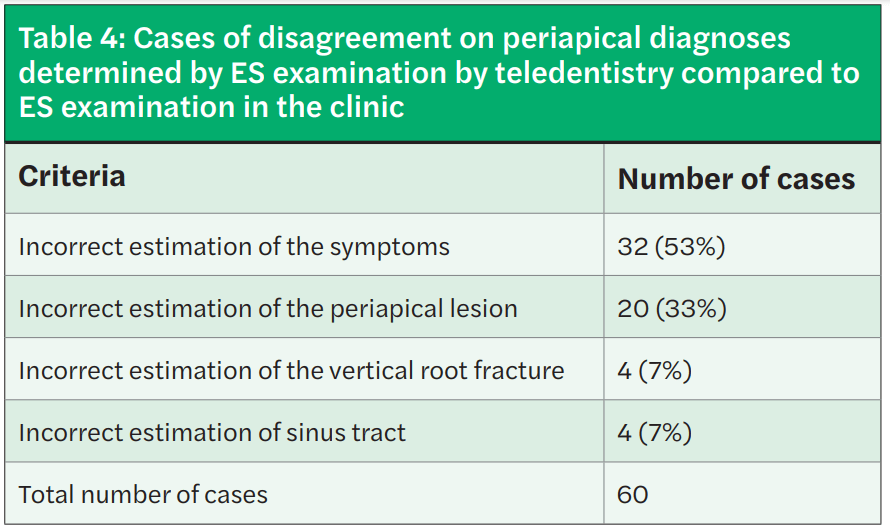

ES by teledentistry compared to ES in the clinic

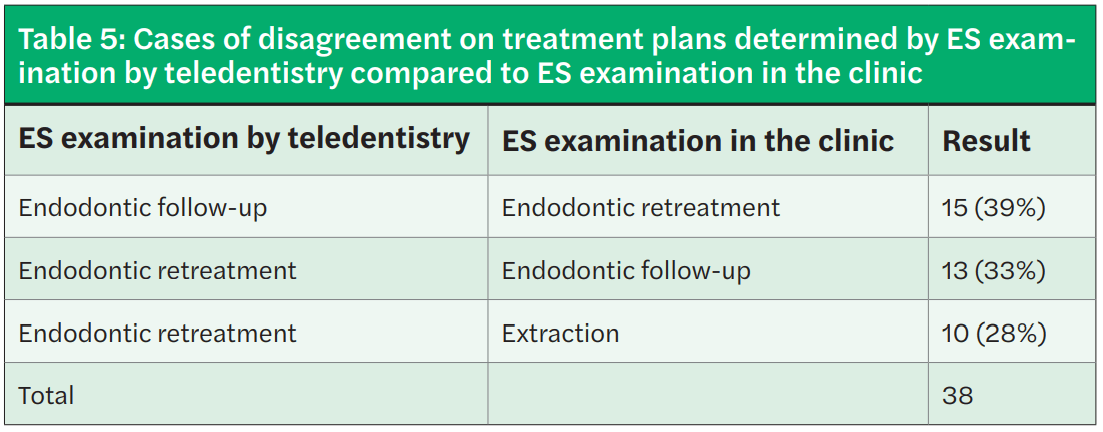

- Among 60 (32%) cases of disagreement on periapical diagnoses, most cases of disagreement were due to incorrect estimation of symptoms (53%) and incorrect estimation of periapical lesions (33%) (Table 4).

- Among 38 (20%) cases of disagreement on treatment plans, most cases (72%) of disagreement were about the necessity of endodontic retreatment (Table 5).

The difference between the methods was significant (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The use of teledentistry for specialist consultations, diagnoses, and treatment planning will enable more affordable and convenient decision-making. The COVID-19 pandemic created challenges in dentistry across the globe.7 Examination and dental treatment involve interaction with the patient, consisting of inspection, diagnosis, and intervention. As a result, during the current pandemic, most routine dental procedures worldwide were suspended, and only emergency dental procedures and surgeries were being performed.7,8

In situations such as this, teledentistry can provide an innovative solution to continue dental practice during the current pandemic and beyond.9 In this research, the validity of diagnoses and treatment plans by ESIC, EST, and GPIC was compared, and complete agreement on pulp diagnoses was found among the three methods. However, partial agreement on periapical diagnoses and treatment plans was found between GPIC and ESIC and between ESIC and EST.

Different diagnostic evaluations and treatment plans between GPs and ESs were previously studied in different dentistry fields: Tamse, et al., 2011 reported that only 33.8% of vertical root fractures were diagnosed by GPs;10 Shemesh, et al., 2018, found that 37% of external invasive root resorptions were not diagnosed by GPs;11 Al-Haj Ali, et al., 2020, demonstrated insufficient knowledge on the emergency management of complicated crown fractures of immature permanent teeth,12 and Alkhalifah, et al., 2017, revealed large differences in treatment planning approaches for cracked teeth between GPs and specialists.13 In our study, the disagreement percentages, which are similar to those of the preceding studies, indicate the inaccuracy of clinical and radiographic evaluations by GPs.

Moreover, the present study revealed different evaluations of diagnoses and treatment plans between ESIC and EST. EST diagnoses and treatment plan formulations were based on GPs’ evaluations of the results of clinical and radiographical examinations. Incorrect estimations of symptoms, incorrect intraoral clinical examination methods, and incorrect radiographical periapical lesion evaluations by GPs might lead to incorrect diagnoses and treatment plan formulations by ESs. Bogari, et al., 2019, revealed differences in examination and diagnostic methods among general dental practitioners in endodontic treatment and reported that only 55.5% thought that percussion was a reliable method of diagnosis, which can lead to misdiagnosis and an incorrect treatment plan.14 The different evaluation of radiographs by the same dentist that was described by Goldman, et al., 1972, might also explain the difference between ESIC and EST.15

Balto, et al., 2004, compared retreatment decisions between general dental practitioners and endodontists. Similar to our results, he found significantly different decisions between these two groups regarding retreatment cases.16

Conclusions

Continuing endodontic education for general practitioners for accurate estimation of symptoms and clinical findings will lead to better and more successful teledentistry and could reduce the number of referrals to specialists, reduce the waiting time for appointments, and minimalize the in-person interaction between patients and dentists/dental clinic staff, which is crucial during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Highlights

- There is a low percentage of agreement on diagnoses and treatment plans determined by general practitioners and endodontists using teledentistry compared to diagnoses and treatment plans determined by endodontists in the

- Continuing endodontic education for general practitioners will improve the accuracy of diagnoses and treatment plans by teledentistry.

- Teledentistry can serve as a crucial tool during the Covid-19 pandemic and can reduce the waiting time for appointments and minimalize the interaction between patients and dental clinic staff.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

If you are already utilizing teledentistry, remember to maximize your marketing regarding your patients’ increased options. Read “Telemedicine marketing checklist: 10 things endodontists should do” by Rachael Sauceman here: https://endopracticeus.com/telemedicine-marketing-checklist-10-things-endodontists-should-do/

- Kmucha ST. Physician liability issues and telemedicine: Part 3 of 3. Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95(1):12-14.

- Yan Velsen L, Wildevuur S, Flierman I, et al. Trust in telemedicine portals for rehabilitation care: an exploratory focus group study with patients and healthcare professionals. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:11.

- Jampani ND, Nutalapati R, Dontula BS, Boyapati R. Applications of teledentistry: A literature review and update. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2011;1(2):37-44.

- Fricton J, Chen H. Using Teledentistry to Improve Access to Dental Care for the Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53(3):537-548.

- Reddy KV. Using teledentistry for providing the specialist access to rural Indians. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22(2):189.

- Bhambal A, Saxena S, Balsaraf S. Teledentistry: potentials unexplored! J Int Oral Health.2010;2(3):1-6.

- Ghai S. Teledentistry during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(5): 933-935.

- Rocca MA, Kudryk VL , Pajak JC, Morris T. The evolution of a teledentistry system within the Department of Defense. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999;921-924.

- Alabdullah JH, Daniel SJ. A systematic review on the validity of teledentistry. Telemed J E Health.2018;24(8):639-648.

- Tamse A, Fuss Z, Lustig J, Kaplavi J. An Evaluation of Endodontically Treated Vertically Fractured Teeth. J Endod. 1999;25(7):506-508.

- Shemesh A, Levin A, Ben Itzhak, et al. External invasive resorption: Possible coexisting factors and demographic and clinical characteristics. Aust Endod J. 2018;45(2):141-145.

- Al-Haj Ali, Algarawi SA, Alrubaian AM, Alasqah AI. Knowledge of General Dental Practitioners and Specialists about Emergency Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries in Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020:6059346.

- Akhalifah S, Sharma ON, AJ Moule. Treatment of cracked teeth. J Endod. 2017;43(9):1579-1586.

- Bogari DF, Alzebiani NA, Mansouri RM, et al. The knowledge and attitude of general dental practitioners toward the proper standards of care while managing endodontic patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Endod J. 2019; 9(1):40-50.

- Goldman M, Pearson AH, Darzenta N. Endodontic success — who’s reading the radiograph. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;33(3):432-437.

- Balto HA, Al-Madi EM. A comparison of retreatment decisions among general dental practitioners and endodontists. J Dent Educ. 2004;68(8):872-879.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..