Drs. Juliana Larocca de Geus, Abel Barreto Jr., Márcia Fernanda de Rezende Siqueira, Jane Kenya Nogueira da Costa, and Alessandra Reis show how paraendodontic surgery on a periapical lesion can lead to a positive outcome.

Drs. Juliana Larocca de Geus, Abel Barreto Jr., Márcia Fernanda de Rezende Siqueira, Jane Kenya Nogueira da Costa, and Alessandra Reis document their success in the surgical treatment of the periapical lesion

Abstract

This manuscript presents a case report of the surgical management of a periapical lesion located in a mandibular incisor, showing a 6-month follow-up. The purpose of paraendodontic surgery is to solve problems that could not be solved by conventional endodontic treatment, or when such treatment is impossible to perform. In the present report, there was no possibility of conventional root canal obturation due to the presence of exudate within the root canal, which did not cease even after changes of intracanal medication. Parendodontic surgery was performed through curettage, apicoectomy, and trans-surgical filling. The authors conclude that the case report showed success in the surgical treatment of the periapical lesion, where the apical area already showed a great bone regeneration after 6 months.

Introduction

Endodontic treatment should provide complete obliteration of the entire root canal system. The establishment of suitable sealing is intended to prevent microorganisms and/or endotoxins from reaching apical and periapical tissues.1

Due to evolution in the biological, scientific, and technical areas, root canal cleaning and shaping procedures have been increasing success rates ranging from 65% to 90%.2 But despite all the growth, endodontic treatments continue to be performed through technical steps that are liable to fail.3

Paraendodontic surgery is indicated in the cases with the following features:

- persistent periapical infections with chronicity and extensive apical radiolucent area

- restricted coronal access due to insufficient retrograde sealing

- root pins that are impossible to remove/perforate

- fracture of the apical third

- pulp calcifications in the cervical and middle third4

The most used surgical modalities are periapical curettage, apicectomy, apicectomy with retrograde obturation, apicectomy with instrumentation and root canal obturation via retrograde and root canal obturation simultaneously with the surgical procedure.5

Periapical curettage is a surgical procedure whose purpose is to remove pathological tissue in a lesion at the apical level of a tooth.5 Apicoectomy is the surgical removal of the apical portion of a tooth.6 The canal obturation simultaneous to the surgical procedure consists of periapical curettage with apicoectomy of a tooth, followed by conventional filling of the canal system during the surgical procedure. It is indicated to resolve cases of extensive chronic periapical lesions in which the canal is well instrumented and numerous calcium hydroxide exchanges have already been made; however, there is presence of inflammatory exudate impeding the conclusion of the treatment,5 as occurred in the case report that follows.

The objective of this study is to demonstrate the treatment of apical lesion with persistent exudation through a case report.

Case report

Patient H.S., a 32-year-old male, attended the endodontic specialization course of the Brazilian Dental Association of Ponta Grossa and was referred by a dental surgeon who could not fill the mandibular left central incisor (tooth No. 31) due to persistent exudation. The dental surgeon had already undergone some intracanal medication changes with calcium hydroxide with an interval of 30 days, and even then the exudation persisted.

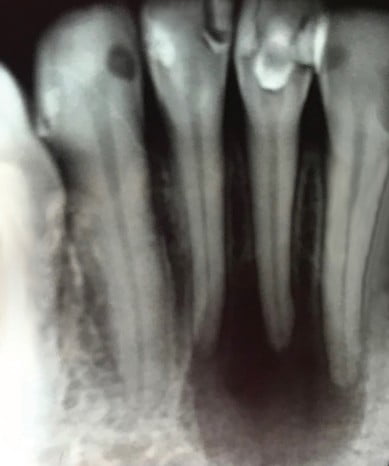

After radiography of the tooth (Figure 1), the presence of a circumscribed radiolucent lesion of considerable size indicative of periapical cyst was observed. A pulp sensitivity test was performed through the cold test on the adjacent teeth, and all responded positively, indicating pulp vitality.

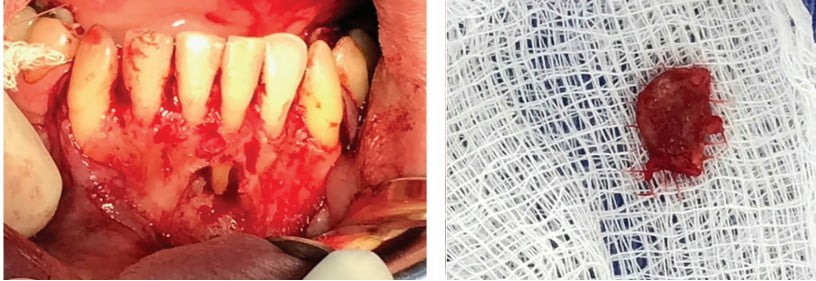

It was decided to perform the parendodontic surgery of the tooth in question. For this, access to the apical lesion was performed through an envelope incision with two relaxing incisions in the canine region (Figure 2).

The curettage of the periapical region was performed, and the lesion was removed (Figure 3). Then the instrumentation was performed with manual files up to No. 40 K-file (Dentsply Sirona, Ballaigues, Switzerland), and the canal was filled with gutta percha and a calcium hydroxide-based sealer (Sealapex™, SybronEndo — Kerr Endodontics, Orange, California) (Figure 4). After that, an apicoectomy of a tooth was performed (Figure 5) with the high-speed Endo-Z™ FG drill (Dentsply). After these procedures, the suture was performed with several simple stitches (Figure 6).

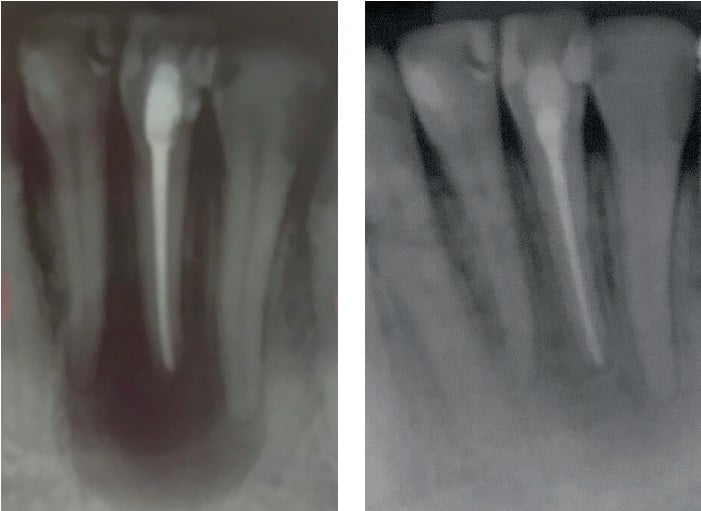

Figure 7 shows the the immediate final radiographic appearance.

Immediately after obturation, coronary shielding was performed by means of composite resin restoration. After the surgical procedure, the patient was prescribed amoxicillin 500 mg for 7 days, paracetamol 750 mg for 1 day, in addition to dexamethasone 4 mg for a period of 2 days.

After 6 months of surgery, bone regeneration was observed in the apical region (Figure 8), the patient was asymptomatic, and the adjacent teeth had vitality.

Discussion

Several authors have reported cases of paraendodontic surgery in the literature, showing the diversity of clinical situations and techniques employed.

The surgical exposure of the apex facilitates the biomechanics of the root canal, allowing a more efficient filling and a vigorous condensation without the concern of extravasation of the obturator material. By removing the pathological material from the periapical area, a duct absent from exudation is obtained, favoring the complete obturation and regeneration of the supporting tissue.7

Some factors could affect the prognosis of periapical surgery. Examples follow:

- systemic conditions of the patient8

- the involved tooth, amount and location of bone resorption, previous quality of treatment or retreatment performed

- degree of occlusal microleakage in restorations

- surgical restorative materials, involved technique

- the surgeon’s skill and experience9

The rates of success and failure in paraendodontic surgeries are quite variable. It should be emphasized that surgery should only be performed after conventional endodontic treatment, or when endodontic risk and benefit indexes result in an uncertain prognosis of success.10 The present case is in accordance with this recommendation on performing the parendodontic surgery only after attempts to make the filling of the root canal by conventional endodontics.

It has already been shown that a correct instrumentation of the canal accompanied by abundant irrigation11-13 is able to drastically reduce the number of bacteria, allowing the root canal obturation. In the case reported, there was difficulty in clearing the infection, since the area involved was extensive; and even using intracanal medication, there was no expected result.

After 6 months, radiographically, periapical repair, and clinically no symptomatology were observed, confirming the success of the procedure.

It is important to emphasize that no paraendodontic surgery will result in success if the canal is not well sealed or if it is not possible, through surgery, to improve its sealing conditions.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the paraendodontic surgery was effective in the removal of the periapical lesion, promoting a good result after 6 months of follow-up. In addition, it was the only way to achieve the root canal filling due to persistent exudate.

Read the technique that Drs. Fernando Muñoz Ayón, Jorge Paredes Vieyra, and Victor Manuel de la Torre Martínez used to treat a periapical lesion in “Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment of extensive periapical lesions” here:

https://endopracticeus.com/ce-articles/nonsurgical-endodontic-retreatment-of-extensive-periapical-lesions/.

- Chugal N, Mallya SM, Kahler B, Lin LM. Endodontic Treatment Outcomes. Dent Clin North Am. 2017;61(1):59-80.

- Iqbal MK, Kim S. A review of factors influencing treatment planning decisions of single-tooth implants versus preserving natural teeth with nonsurgical endodontic therapy. J. Endod. 2008;34:519-29.

- Siqueira JF Jr. Aetiology of root canal treatment failure: why well-treated teeth can fail. Int Endod J. 2001;34(1):1-10.

- Love RM. Persistent endodontic infection—re-treatment or surgery? Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg. 2012;21:103-105.

- Gutmann JL, Harrison JW, Posterior endodontic surgery: anatomical considerations and clinical techniques. Int Endod J. 1985;18:8-34.

- Nasseh AA, Brave D. Apicoectomy: The Misunderstood Surgical Procedure. Dent Today. 2015;34(2):130-136.

- Chércoles-Ruiz A, Sánchez-Torres A, Gay-Escoda C. Endodontics, Endodontic Retreatment, and Apical Surgery Versus Tooth Extraction and Implant Placement: A Systematic Review. J Endod. 2017;43(5):679-686.

- Aminoshariae A, Kulild JC, Mickel A, Fouad AF. Association between Systemic Diseases and Endodontic Outcome: A Systematic Review. J Endod. 2017;43(4):514-519.

- Lustmann J, Friedman S, Shaharabany V. Relation of pre and intra operative factors to prognosis of posterior apical surgery. J Endod. 1991:17:239-241.

- Öğütlü F, Karac, İ. Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of Apical Surgery: A Clinical Study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;17(1):75-83.

- Haapasalo M, Shen Y, Wang Z, Gao Y. Irrigation in endodontics. Br Dent J. 2014;216(6):299-303.

- Rodrigues RCV, Zandi H, Kristoffersen AK, et al. Influence of the Apical Preparation Size and the Irrigant Type on Bacterial Reduction in Root Canal-treated Teeth with Apical Periodontitis. J Endod. 2017;43(7):1058-1063

- Navabi AA, Khademi AA, Khabiri M, Zarean P, Zarean P. Comparative evaluation of Enterococcus faecalis counts in different tapers of rotary system and irrigation fluids: An ex vivo study. Dent Res J. 2018;15(3):173-179.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..