CE Expiration Date:

CEU (Continuing Education Unit): Credit(s)

AGD Code:

Educational aims and objectives

This article aims to explore how the internal anatomy of the pulp chamber and the root canal system remains crucial to increase the efficiency and, subsequently, the rate of clinical success of endodontic treatment.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Identify some of the main causes of endodontic treatment failure.

- Recognize the use of the T-shaped access cavity modification as an approach to root canals.

- Recognize the use of computed tomography as an additional diagnostic tool as useful to detect anatomical variations.

- Realize the importance of optical magnification, dyes, and ultrasound tips to enhance the visualization of the pulp chamber and extra canal orifices.

Drs. Yuriy Riznyk, Svitlana Riznyk, and Khrystyna Sydorak address the complex presence of maxillary first molars with three root canals and how modern instrumentation can make this less daunting to treat.

Drs. Yuriy Riznyk, Svitlana Riznyk, and Khrystyna Sydorak discuss how modern instrumentation can make it more viable to tackle rare and complex root canal systems

The development of equipment and instrumentation techniques has made it possible to solve difficult clinical cases in endodontics (Berutti, et al., 2009). However, irrespective of the continuous improvement of technology, the profound knowledge of the internal anatomy of the pulp chamber and the root canal system remains crucial to increase the efficiency and, subsequently, the rate of clinical success of endodontic treatment (Vertucci, 2005; Baratto, Filho, et al., 2009; Fava, 2001).

The incomplete instrumentation, irrigation, and poor quality of obturation of the root canal system are the main causes of endodontic failure (Leonardo, 1998). Song, et al. (2011), reported that 11.7% of possible causes of failure in the previous root canal treatment of upper premolars were missed root canals.

Among permanent teeth, the roots of maxillary first premolars often have two conical roots — i.e., one buccal and one palatal root, which may present root fusion. The buccal root may be further subdivided into two, causing the tooth to have three canals: a palatal, a distobuccal, and a mesiobuccal canal (Pécora, et al., 1992; Awawdeh, et al., 2008).

The incidence of one root canal does not exceed 31% of all cases; two root canals varies from 67% to 72% (Carns and Skidmore, 1983; Bellizi and Hartwell, 1985; Vertucci and Gegaulf, 1979; Sert and Bayirli, 2004). Carns and Skidmore (1973) found 6% of maxillary first premolars to have three canals, all of which were present as one canal in each of three roots. Vertucci and Gegaulf (1979) found 5% of maxillary first premolars to have three canals: 0.5% existed as three canals in a single root; 0.5% existed as two canals in one root and one canal in a second root; and 4% existed as one canal in each of three separate roots.

It is worth mentioning that visualization of three-canalled maxillary premolars on preoperative radiographs can often be difficult. Thus, a careful examination of several preoperative radiographs or the use of computed tomography as an additional diagnostic tool can be useful to detect anatomical variations (Sachdeva, et al., 2008; de Paula, et al., 2013).

The use of the T-shaped access cavity modification may be helpful for correct approach to all of the root canals (Balleri, et al., 1997). Optical magnification (Baldassari-Cruz, et al., 2002; Yoshioka, et al., 2002), dyes, and ultrasound tips are important aids in endodontics because these facilitate locating canals and approaching them correctly.

Case report 1 (Figures 1, 2, and 3)

A 28-year-old male patient with a non-contributory medical history applied to the clinic with the chief complaint of spontaneous pain in the upper right region of the jaw for the previous 2 days.

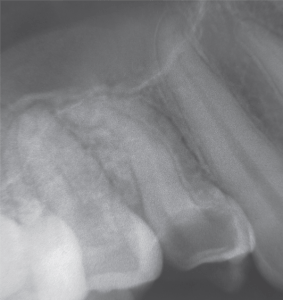

On clinical examination, a deep carious lesion affecting almost the whole crown was seen in tooth UR4. Vitality testing of the involved tooth with cold testing caused an intense lingering pain. Percussion test was negative. Investigations for swelling, sinus tract, and periodontal involvement were negative. A preoperative radiograph (Figure 1) revealed radiolucency on the occlusal-distal surfaces of the crown, approaching the pulp space and vague two separate roots in the first upper premolar. A diagnosis of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis was made judging by the clinical and radiographic examination, and conservative endodontic treatment was recommended.

After local anesthesia with 4% Ubistesin 1:100000 (3M ESPE) and rubber dam isolation of the operative area, pulp chamber access was performed using a long neck round-shaped drills, cone-shaped drills with nonaggressive tip, and ultrasonic tips.

While preparing the access to the root canal orifices, care was taken to save as much healthy tissue as possible. The examination of the pulp chamber floor was performed with the DG16 endodontic probe and dye under optical magnification. The outline of the access cavity was modified as suggested by Balleri, et al., (1997). The pulp chamber was rinsed with 6% sodium hypochlorite. The canals were negotiated with a slightly bent 10 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer) using a watch-winding motion and slow pushing movements toward the apical constriction. The patency was established at working length with 10 K-file using I-PEX apex locator (NSK, Japan) and confirmed radiographically. The glide path was performed using size 15 and 20 K-files NITIFLEX® (Dentsply Maillefer). The instrumentation of the coronal third of the root was performed using the ProTaper Next™ XA (Dentsply Maillefer) instrument. The rest of root canal system was prepared with XP-endo shaper (Schottlander). The preparation was completed with 35/.04 BT-Race (Schottlander). At each change of instrument, the canals were irrigated with 2 ml of 6% sodium hypochlorite solution.

At the end of biomechanical preparation, 17% EDTA (Cercamed, Poland) was applied for 1 minute to remove smear layer, and the final washing was performed with copious volume of 6% sodium hypochlorite. The solutions were activated by XP-endo finisher (Schottlander) within 1 minute, applying slow, gentle longitudinal movements of 7 mm-8 mm to cover the entire length of the canal. Before the obturation, all canals were rinsed with sterile saline 0.9%.

The canals were partially dried with paper points and obturated by cold hydrodynamic obturation technique of gutta percha and premixed bioceramic obturation material TotalFill® (Schottlander).

The pulp chamber was cleaned to remove the excess of gutta percha and bioceramic sealer, and the tooth was temporarily restored with glass ionomer cement Fuji IX GP (GC UK). The patient was referred for the orthopedic treatment of UR4 tooth.

Case report 2

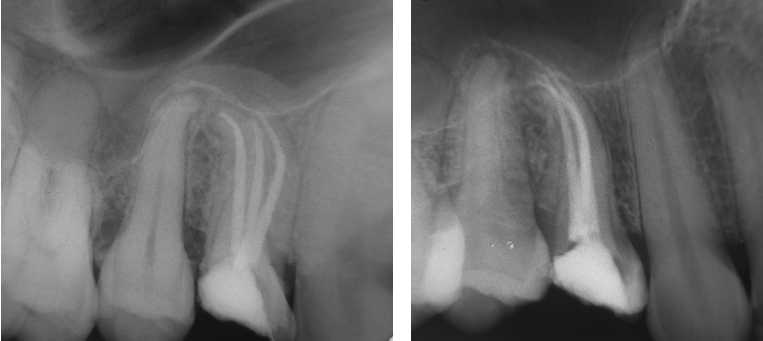

A 22-year-old female was referred to the clinic by the dentist after the previously initiated therapy with a history of symptomatic periapical periodontitis. Clinically, there was a cement filling at the occlusal-distal surface of the tooth UL4. The UL4 was not sensitive to cold testing. Investigations for swelling, sinus tract, and periodontal involvement were negative. Preoperative radiograph (Figure 4) revealed no periapical involvement of the periodontal ligament space and a vague outline of two roots. The radiopaque matter was found in the root canals. Conservative endodontic treatment of UL4 was recommended.

Local anesthesia with 4% Ubistesin™ 1:200000 (3M ESPE) was performed before placement of rubber dam. The tooth was isolated, access was prepared, and the floor of the pulp chamber was examined with an optical magnification, dye, and endodontic probe DG 16. The residue of Ca(OH)2 paste was found in the two root canals. The third (mesio-buccal) root canal was revealed, and access cavity was modified. Three root canals were explored with size 10 K-file. The working lengths were estimated using an apex locator I-PEX (NSK UK) and then confirmed with a radiograph. Two buccal canals were connected near the apical constriction, and the palatal canal was separate.

The root canal system was prepared with X1, X2, X3 ProTaper Next (Dentsply Maillefer) and stainless steel K-files (Dentsply Maillefer). At each change of instrument, the canals were irrigated with 2 ml of 6% sodium hypochlorite solution. The master apical file in all canals was an ISO size 45.

Before the obturation 17% EDTA (Cercamed, Poland) and copious volume of 6% sodium hypochloride were used alternately, followed by the saline. The final washing was performed with 2% digluconate chlorhexidine for 10 minutes, followed by the saline. All of the solutions were activated with XP-endo finisher (Schottlander) within 1 minute.

The canals were partially dried with paper points and obturated by cold hydrodynamic obturation technique with gutta percha and premixed bioceramic obturation material TotalFill (Schottlander).

Light-cured composite was used for the temporary sealing. The patient was referred for the orthopedic treatment of UL4.

Discussion

An accurate diagnosis of the anatomy of the root canal system is a prerequisite for successful endodontic treatment (Aguiar, et al., 2010). The process of identifying and accessing root canals is particularly challenging in endodontic treatment of teeth with atypical canal configuration.

The radiographic signs that demonstrate the presence of anatomical variations must be considered as an important condition when planning the dental treatment (Vertucci, 2005). However, it should be noted that visualization of three canals in a maxillary premolar on preoperative radiographs could often be difficult, because the preoperative radiography gives a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional object. Advanced diagnostic tools such as cone-beam computed tomography might give a more accurate picture of root canal morphology.

The access modification can be useful for an endodontist for easy and correct approach to every root canal.

Appropriate shaping and cleaning of the root canal system with proper instruments can improve the quality of root canal system cleaning (Adbam, et al., 2017; Sanabria-Liviac, et al., 2017; Adbam, et al., 2016).

A profound knowledge of the internal anatomy of roots, correct diagnosis, and appropriate shaping and cleaning of the root canal system usually leads to the successful clinical outcome (Schäfer and Bossmann, 2001).

Conclusions

Morphological variations of the root canal system should always be considered before beginning treatment. According to the literature, three root canals in the first upper premolar are found in 0.5-6% of cases. Thorough clinical examination and comprehensive analysis of angled radiographs are essential for the successful endodontic treatment. In daily practice, it is important to use an optical magnification, dyes, and ultrasound tips because these methods can enhance the visualization of the pulp chamber and extra canal orifices, and consequently, increase the clinical success of endodontic treatment.

https://endopracticeus.com/endo-essentials/top-ten-tips-anatomy-root-canal-system/

Dr. Tony Druttman has written about the tooth anatomy and how to detect vital information including a tooth with three root canals in his article, “Top ten tips: Anatomy of the root canal system.”

References

- Adbam Azim A, Hacer Aksel, Tingting Zhuang, et al. Efficacy of 4 irrigation protocols in killing bacteria colonized in dentinal tubules examined by novel confocal laser scanning microscope analysis. J Endod. 2016;42(6):928-934.

- Azim AA, Plasecki L, da Silva Neto UX, et al. XP-Shaper, A novel adaptive core rotary instrument: Micro-computed tomographic analysis of its shaping abilities. J Endod. 2017;43(9):1532-1538.

- Aguiar C, Mendes D, Câmara A, Figueiredo J. Endodontic treatment of a mandibular second premolar with three root canals. JCDP. 2010;11(2):78-84.

- Awawdeh L, Abdullah H, Al-Qudah A. Root form and canal morphology of Jordanian maxillary first premolars. J Endod. 2008;34(8):956-961.

- Baldassari-Cruz LA, Lilly JP, Rivera EM. The influence of dental operating microscope in locating the mesiolingual canal orifice. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93(2):190-194.

- Balleri P, Gesi A, Ferrari M. Primer premolar superior com tres raices. Endodontic Practice US. 1997;3:13-15.

- Baratto Filho F, Zaitter S, Haragushiku GA, et al. Analysis of the internal anatomy of maxillary first molars by using different methods, J Endod. 2009;35(3):337-342.

- Berutti EG, Cantatore A, Castellucci, et al. Use of nickel-titanium rotary PathFile to create the glide path: comparison with manual preflaring in simulated root canals. J Endod. 2009;35(3):408-412.

- Bellizi R, Hartwell G. Radiographic evaluation of root canal anatomy of in-vivo endodontically treated maxillary premolars. J Endod. 1985;11(1):37-41.

- Carns EJ, Skidmore AE. Configuration and derivatives of root canals of maxillary first premolars. Oral surg. 1973;36:880-886.

- de Paula AF, Brito-Júnior M, Quintino AC, et al. Three independent mesial canals in a mandibular molar: four-year follow-up of a case using cone beam computed tomography. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013.891–849

- Fava LR. Root canal treatment in an unusual maxillary first molar: A case report. Int Endod J. 2001;4:649-653.

- Leonardo MR. Aspectos anatomicos da cavidade pulpar: relacoes com o tratamento de canais radiculares. In: Leonardo MR, Leal JM (eds). Endodontia: tratamento de canais radiculares. 3rd ed. Sao Paulo: Panamericana; 1998.

- Pécora JD, Saquy PC, Sousa Neto MD, Woelfel JB. Root form and canal anatomy of maxillary first premolars. Braz Dent J. 1992;2(2):87-94.

- Sachdeva GS, Ballal S, Gopikrishna V, Kandaswamy D. Endodontic management of a mandibular second premolar with four roots and four root canals with aid of spiral computed tomography: a case report. J Endod. 2008;34(1):104-107.

- Sanabria-Liviac D, Moldauer BI, Garcia-Godoy F, et al. Comparison of the XP-finisher file system and passive ultrasonic irrigation (PUI) on smear layer removal after root canal instrumentation effectiveness of two irrigation methods on smear layer removal. J Dent Oral Health. 2017;4:101.

- Schäfer E, Bossmann K. Antimicrobial efficacy of chloroxylenol and chlorhexidine in the treatment of infected root canals. Am J Dent. 2001;14(4):233-237.

- Sert S, Bayirli GS. Evaluation of the root canal configurations of the mandibular and maxillary permanent teeth by gender in the Turkish population. J Endod. 2004;30:391.

- Song M, Kim HC, Lee W, Kim E. Analysis of the Cause of Failure in Nonsurgical Endodontic Treatment by Microscopic Inspection during Endodontic Microsurgery. J Endod. 2011;37(11):1516-1519.

- Vertucci FJ.2005; Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures, Endodontic Topics. 1979;10(1):3-29.

- Vertucci FJ, Gegaulf A. Root canal morphology of the maxillary first premolar. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;99(2):194-198.

- Yoshioka T, Kobayashi C, Suda H. Detection rate of root canal orifices with a microscope. J Endod. 2002;28:452-453.