Stefanya Dias de Oliveira and colleagues explore the use of bioceramics when treating extensive periapical lesions.

Stefanya Dias de Oliveira, Artur Henrique Cabral, Danielly Davi Correia Lima, Alexia da Mata Galvão, Dr. Gabriella Lopes de Rezende Barbosa, Larissa Rodrigues Santiago, and Dr. Maria Antonieta Veloso Carvalho de Oliveira show how bioceramics help the healing process

Abstract

This study reports the clinical case of a 56-year-old male patient with extensive periapical lesions associated with teeth Nos. 7, 9, and 10, suggestive of chronic apical periodontitis on radiographic examination and disruption of the cortical bone on CBCT examination. Conventional endodontic treatment and retreatment were performed associated with endodontic surgery using bioceramic materials with 34 months of follow-up. At follow-up, there was bone formation around teeth Nos. 7 and 10, a significant decrease in the size of the lesion on tooth No. 9, and no symptoms. In view of the histopathological diagnosis of cystic lesions of odontogenic origin, it was found that endodontic surgery was necessary as a complement to conventional treatment. The use of bioceramics probably helped in the bone healing process, enabling tooth maintenance.

Introduction

Endodontic treatment aims to promote the disinfection of the root canal system in order to eliminate necrotic tissue, reduce the load of microorganisms, and model and seal the conduits to minimize the risk of recontamination.1,2

Even though the success rates of root canal therapy are around 97%, posttreatment problems can occur3 due to inaccessibility to all apical ramifications for cleaning and sealing.4

When conventional endodontics fail, and it is no longer possible to perform orthograde retreatment, endodontic surgery is the method indicated for treatment.2,4,5,6 By removing diseased tissue, apical surgery also encompasses sealing the root canal system, preventing the colonization of any remaining bacteria in the periradicular tissues and the appearance of lesions.5,7,8

Studies show that the surgical approach has great predictability because of the final apical filling probably due to the essential characteristics present in the filling materials.4,9,10 Bioceramic cement was developed as a retrograde filling material because it has characteristics such as biocompatibility, encouraging the growth of natural tissues, and upon setting was insoluble preventing recurrent apical leakage. It has bioactive capacity and low toxicity, allows a hermetic seal with good dimensional stability with antibacterial and antifungal activity, in addition to being bio-inert.11,12,13,14,15,16

The aim of this article was to report a clinical case of a patient with an extensive periapical lesion who underwent conventional endodontic treatment and retreatment associated with surgery on teeth Nos. 7, 9, and 10 using bioceramic materials with 34 months of follow-up.

Case report

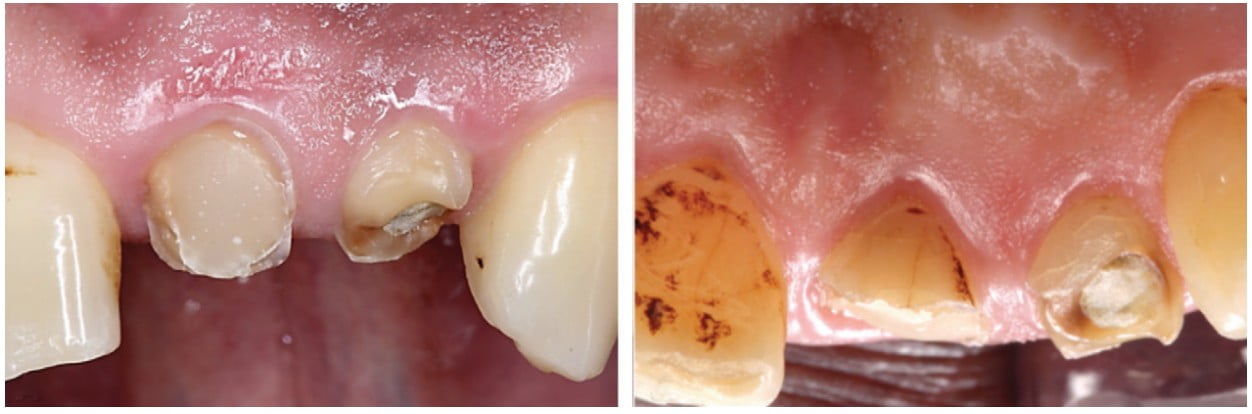

The patient, a 56-year-old man, who attended the clinic of the Stomatological Diagnosis Unit of the School of Dentistry of the Federal University of Uberlândia (FOUFU), presented complaining of pain and dental fracture. In the health history review, the patient reported a previous history of dental caries. Clinical examination revealed the presence of a coronal fracture on teeth Nos. 7 and 9, coronal opening with provisional sealing on tooth 10 (Figure 1), and absence of symptoms in the vertical and horizontal percussion tests and in the cold thermal sensitivity test (Hygenic® Endo Ice® spray, Maquira Dental Products Industry S.A, Maringá, PR, Brazil).

Radiographic examination revealed the presence of an extensive periapical lesion associated with teeth 7, 9, and 10, and prior endodontic treatment on teeth Nos. 7 and 10 (Figure 2).

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) was also performed using a Gendex CB-500 scanner (Gendex Dental Systems, Hatfield, Pennsylvania). It showed the real dimension of bone loss with the presence of disruption of the buccal and palatal cortical bone (Figure 3) with an epicenter in the region of tooth No. 7 and measuring 11.15 mm x 16.98 mm, and measuring 12.45 mm x 19.24 mm in the region of teeth Nos. 9 and 10 with the epicenter close to the apex of tooth No. 9. The likely clinical/radiographic diagnosis was chronic apical periodontitis.

After coronal opening, endodontic retreatment of teeth Nos. 7 and 10 was performed using a Gates-Glidden drill (Dentsply Sirona, New York, New York), Hedströen files (Dentsply Sirona) and ProTaper® retreatment rotary files (Dentsply Sirona) to remove the filling material. In tooth No. 7, there was a deviation of the canal to the mesial side during the attempt to remove the filling in the apical third, preventing the total removal of the gutta percha from this region. The ProTaper Next™ system (Dentsply Sirona, New York) up to the X3 file was used for the biomechanical preparation of the three teeth. The canals were irrigated throughout the treatment with 1% sodium hypochlorite (Biodinâmica, Ibiraporã, PR, Brazil) and saline solution (Biodinâmica, Ibiraporã, PR, Brazil), and the teeth were provisionally sealed with glass ionomer-based cement (FGM Dental Group, Stamford, Connecticut).

All three teeth underwent weekly changes of bioceramic intracanal medication (Bio-C® Temp – Angelus Dental Products Industry S.A., Londrina, PR, Brazil) for 1 month. Tooth No. 9 showed the presence of exudate inside the root canal during the 30 days of treatment.

After several factors — e.g, the size of the lesions, the continuous accumulation of purulent secretion on tooth No. 9, the difficulties in carrying out clinical care arising from the patient’s systemic problems, the dependence on the calendar of a multidisciplinary team to perform the surgical process, and the end of the academic semester at FOUFU that would last 4 months — it was not possible to change the intracanal medication until the exudate ceased. Also, taking into consideration the failure of complete removal of gutta percha from tooth No. 7, endodontic surgery was chosen as the treatment approach (Figures 4 and 5). Thus, before surgery, only tooth No. 10 was filled using the lateral and vertical condensation technique with gutta percha (Dentsply Sirona, New York) and bioceramic cement (Bio-C Sealer – Angelus Dental Products Industry S.A., Londrina, PR, Brazil).

Endodontic surgery was performed at the FOUFU surgery clinic by an oral and maxillofacial surgeon. Prior to the beginning of the procedure, antibiotic prophylaxis, antisepsis, oral cavity asepsis, and local anesthesia were performed. A horizontal incision was made with small curvatures in the gingiva inserted 3.0 mm from the gingival sulcus and complemented with two vertical incisions above the maxillary incisors with a scalpel handle and 15 blade providing a Luebke-Ochsenbein flap (submarginal incision flap) technique. Tissue dissection and flap detachment were performed with a Molt periosteal elevator (S.S. White, Duflex, Lakewood, New Jersey), and the osteotomy to access the apices of teeth Nos. 7, 9, and 10 was performed with a carbide drill and a 702 blade in high rotation with abundant irrigation using saline solution (Biodinâmica, Ibiraporã, PR, Brazil). After the osteotomy, the lesions were removed with a Lucas curette (S.S. White/Duflex, Lakewood, New Jersey) (Figure 5A) and placed in a closed container containing 1% formaldehyde and sent for histopathological examination. This examination diagnosed the lesions as cystic of odontogenic origin (Figure 6).

An apioectomy was performed by removing 3.0 mm of the apical portion of the root (Figure 4C) with a conical diamond bur (Kavo, Charlotte, North Carolina) in high rotation at an angle of 45º (Figure 4A). Retrofilling was performed with bioceramic cement (MTA Repair HP – Angelus Dental Products Industry S.A., Londrina, PR, Brazil), and (Figure 4B) with the aid of an MTA applicator (Angelus Dental Products Industry S.A., Londrina, PR, Brazil). The suture was performed using 5-0 absorbable sutures (Ethicon; Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey).

Fifteen days after surgery, teeth Nos. 7 and 9 were filled using a No. 50 McSpadden compactor (Dentsply Sirona, New York). At the first follow-up visit after 3 months (Figure 7), the patient had no painful symptoms and no purulent secretion. However, it was radiographically observed that the retrofilling material of tooth No. 7 was displaced (Figure 7A).

Due to the patient’s health problems, only 9 months after the end of endodontic treatment, a new intervention was possible on tooth No. 7 to replace the retrofilling. All surgical procedures were performed in the same way as in the first surgery. The retro-filling was performed with bioceramic cement MTA Repair HP (Angelus Dental Products Industry S.A., Londrina, PR, Brazil).

At the follow-up visit after 34 months (Figure 8), bone neoformation was observed around the three teeth. Comparing the initial CBCT examination with the 34-month examination, the evolution of bone neoformation can be seen (Figure 9).

Discussion

The root canal retreatment performed on teeth Nos. 7 and 10 in the present case had the same objective as the primary treatment, completely eliminating pathogens and making the hermetic seal with bioceramic materials. Studies indicate that persistent lesions in the periapex are not rare, and the prevalence is around 30%.1

The diagnosis of periapical lesions may require more than clinical and histological assessments and intraoral periapical radiographs. In this sense, more advanced methods such as CBCT can offer a higher quality of diagnostic evaluation, allowing an assertive treatment plan and prognosis.17 CBCT was used in the present case with the aim of performing a pre-surgical study, analyzing the teeth and their surrounding structures, helping to determine the actual size of the lesion, evidencing the damage caused such as the disruption of the buccal and palatal cortical bone, and helping in the choice of performing conventional treatment associated with surgery.

The type of lesion is closely related to the success of the treatment. Periapical granuloma-type lesions can be more easily eliminated with conventional treatment, while periapical cysts and extraradicular infections usually do not regress, causing failures in the primary intervention.4 In the present clinical case, in view of the histopathological diagnosis of cystic lesions of odontogenic origin, it was found that endodontic surgery was necessary as a way of complementing the treatment, aiming to eliminate microbial agents inaccessible to conventional endodontic therapy.4,8,18

In the surgical intervention, the removal of the periapical lesion was planned through an osteotomy. The resection of the infected root end was performed with the apical portions apicectomized at 3 mm to reduce 98% of the apical ramifications and 93% of the lateral canals, avoiding the risk of reinfection and eventual failure.8

The filling of the apical system of the root canal was made with a bioceramic material, allowing the healing of the peri-apical tissue through neo-osteogenesis.3,5,12 The osteoconductivity and excellent biocompatibility of bioceramics by the formation of hydroxyapatite allow the interaction with the surrounding tissues, promoting their regeneration from the release of calcium and silicon as well.11,13,15 In the present clinical case, bioceramic materials were used as intracanal medication, sealer in endodontic treatment and retreatment, and as post-surgery retro-filling cement.

Due to the filling of teeth Nos. 7 and 10 after surgery, another surgical procedure was necessary similar to the first to accommodate a new MTA apical plug in tooth No. 7, which was displaced during root canal filling probably due to the pressure exerted in the thermoplastic process of gutta percha.

After 34 months of follow-up, periapical bone formation around teeth Nos. 7 and 10 and a decrease in the size of the lesion on tooth No. 9 were observed, in addition to absence of mobility and of painful symptoms.

Conclusion

In the present clinical case, in view of the histopathological diagnosis of cystic lesions of odontogenic origin, it was found that endodontic surgery was really necessary as a way of complementing the treatment, aiming to eliminate microbial agents inaccessible to conventional endodontic therapy. The use of bioceramics helped in the bone-healing process, enabling tooth maintenance.

For an interesting look at bioceramics and bioactives, check out the CE webinar titled, “Bioceramics: Promising New Frontier or Wild West?” at https://endopracticeus.com/webinar/bioceramics-promising-new-frontier-or-wild-west/.

- Fabbro M, Taschieri S, Taschieri S, Francetti L, Weinstein RL. Surgical versus non-surgical endodontic re-treatment for periradicular lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18(3):1-17.

- Alghamdi F, Alhaddad AJ, Abuzinadah S. Healing of Periapical Lesions After Surgical Endodontic Retreatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020;12:1-9.

- Fabbro MD, Corbella S, Sequeira-Byron P, et al. Endodontic procedures for retreatment of periapical lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(10):1-105.

- Pavelski M, Portinho D, Casagrande-Neto A, Griza GL, Ribeiro RG. Paraendodontic surgery: case report. Revista Gaúcha Odontológica. 2016;64: 460-466.

- Christiansen R, Kirkevang LL, Hørsted-Bindslev P, Wenzel A. Randomized clinical trial of root-end resection followed by root-end filling with mineral trioxide aggregate or smoothing of the orthograde gutta-percha root filling – 1-year follow-up. Int Endod J. 2009;42(4):105-114.

- Karabucak B, Setzer FC. Conventional and surgical retreatment of complex periradicular lesions with periodontal involvement. J Endod. 2009;35(9):1310-1315.

- Pasha S, S Madhu K, Nagaraja S. Treatment outcome of surgical management in endodontic retreatment failure. Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal. 2013;33(3):554-557.

- Kim S, Kratchman S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: a review. J Endod. 2006;32(7):601-623.

- Kruse C, Spin-Neto R, Christiansen R, Wenzel A, Kirkevang LL. Periapical Bone Healing after Apicectomy with and without Retrograde Root Filling with Mineral Trioxide Aggregate: A 6-year Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Endod. 2016;42(4):533-537.

- Safi C, Kohli MR, Kratchman SI, Setzer FC, Karabucak B. Outcome of Endodontic Microsurgery Using Mineral Trioxide Aggregate or Root Repair Material as Root-end Filling Material: A Randomized Controlled Trial with Cone-beam Computed Tomographic Evaluation. J Endod. 2019;45(7):831-839.

- Utneja S, Nawal RR, Talwar S, Verma M. Current perspectives of bio-ceramic technology in endodontics: calcium enriched mixture cement — review of its composition, properties and applications. Restor Dent Endod. 2015;40(1):1-13.

- AL-Haddad A, Che Ab Aziz ZA. Bioceramic-Based Root Canal Sealers: A Review. Int J Biomat. 2016;2016:1-10.

- Jitaru S, Hodisan I, Timis L, Lucian A, Bud M. the use of bioceramics in endodontics — literature review. Clujul Med. 2016;89(4):470-473.

- Raghavendra SS, Jadhav GR, Gathani KM, Kotadia P. bioceramics in endodontics — a review. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2017;51(3 suppl 1):s128-s137.

- Jiménez-Sánchez MC, Segura-Egea JJ, Díaz-Cuenca A. A Microstructure Insight of MTA Repair HP of Rapid Setting Capacity and Bioactive Response. Materials (Basel). 2020;13(7):1-11.

- Zafar K, Jamal S, Ghafoor R. Bio-active cements-Mineral Trioxide Aggregate based calcium silicate materials: a narrative review. J Park Med Assoc. 2020;70(3):497-504.

- Shekhar V, Shashikala K. Cone Beam Computed Tomography Evaluation of the Diagnosis, Treatment Planning, and Long-Term Followup of Large Periapical Lesions Treated by Endodontic Surgery: Two Case Reports. Case Rep Dent. 2013; 2013:1-12.

- Ribeiro FC, Fabri B, Roldi A, Pereira RS, et al. Prevalence of periapical lesions in endodontic treatment teeth. Revista Saúde. 2013;9(4):244-52.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..