Drs. Artur Henrique Cabral, Gabriella Lopes de Rezende Barbosa, Larissa Rodrigues Santiago, Alexia da Mata Galvão, and Maria Antonieta Veloso Carvalho de Oliveira find that efficient surgical retreatment can be achieved with apicectomy and retrofilling procedures combined with endodontic therapy.

Drs. Artur Henrique Cabral, Gabriella Lopes de Rezende Barbosa, Larissa Rodrigues Santiago, Alexia da Mata Galvão, and Maria Antonieta Veloso Carvalho de Oliveira discuss this surgical retreatment as a viable and effective option

Abstract

This article reports the association of endodontic treatment and microsurgery as the treatment choice for an extensive periapical lesion and a recurrent fistula in tooth No. 22 of a 44-year-old female patient. Clinical examinations and periapical radiographs revealed the presence of a palatal fistula and extensive periapical lesion. After biomechanical preparation and 2 months of intracanal medication with calcium hydroxide, the fistula regressed, and the tooth was filled. One month later the fistula reappeared. Then the tooth was reevaluated using cone beam computed tomography, and surgery was performed to remove the lesion, conduct an apicectomy, and retrofill the tooth with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA). The histopathological diagnosis of the lesion was periapical granuloma. Surgical retreatment is a viable and effective option for treating infection and repairing periapical tissue in teeth with persistent fistulas and extensive periapical lesions.

Introduction

The main objective of endodontic treatment is to reduce microorganisms and consequent infections in the root canal.1 This is achieved by cleaning and sealing the root canal to prevent reinfection and to recover or return functional and esthetic aspects of the tooth.2

The success of cleaning and modeling the root canal system has improved due to various technical, scientific, and biological developments. Nevertheless, endodontic treatments are still prone to failures, accidents, and various other complications.3

Given the risks, and especially those related to maintenance or new bacterial infections, nonsurgical retreatment is always the first choice.4 However, endodontic surgery is an excellent alternative for treatment or retreatment of periapical infections that are persistent, chronic, and extensive.5

This paper reports a case of conventional endodontic treatment followed by endodontic microsurgery in a patient with an extensive periapical lesion and recurrent fistula associated with an upper left lateral incisor.

Case report

A 44-year-old female patient presented at the clinic of the School of Dentistry of the Federal University of Uberlandia, Brazil. Six years earlier at the Dental Emergency Room of the same institution, the patient reported a history of facial trauma, pain, and swelling that was treated by draining an abscess and opening the crown of tooth No. 22. The patient remained free of pain and swelling for 2 years after the procedure.

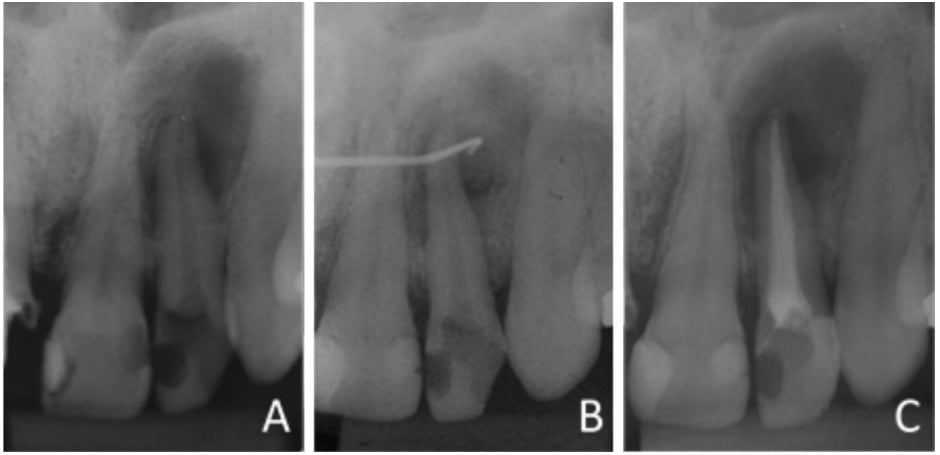

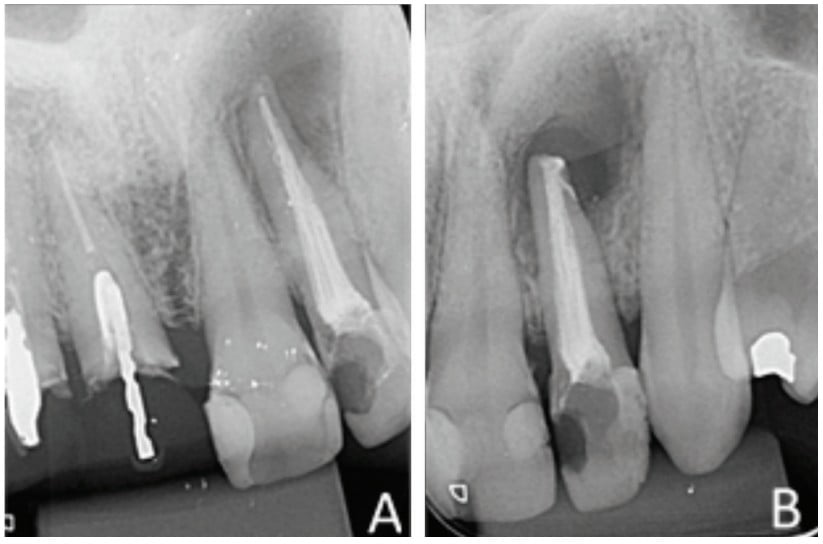

An intraoral clinical examination of tooth No. 22 showed coronary darkening, unsatisfactory resin restorations in proximal teeth, a coronary opening without provisional sealing, and palatal fistula. A periapical radiography showed a broad root canal and a large well-defined unilocular radiolucent lesion associated with the root of tooth No. 22, which suggested a periapical lesion (Figure 1A). The path of the fistula was determined by placing a No. 25 gutta-percha cone (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) in the fistula and then acquiring a new periapical image. This procedure traced the sinus tract and revealed the origin in the apical region of tooth No. 22 (Figure 1B).

Vertical and horizontal percussion tests, and a thermal sensitivity test (Endo Ice® Spray, Hygenic®) showed absence of pain. The suggested clinical/radiographic diagnosis was chronic apical periodontitis.

The root canal instrumentation was performed using the crown-down technique and Hedströen Nos. 15 to 25 hand files (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) on the cervical and middle thirds and Kerr files on the apical third (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). A No. 50 K-File was used with a working length of 21 mm. Foraminal debridement was performed with a No. 15 K-File (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). Progressive neutralization was carried out throughout by abundant irrigation using a 1% sodium hypochlorite and saline solution, applied with a 25 x 4 hypodermic needle (Ultradent). After instrumentation, the canal was filled with intracanal calcium hydroxide (Ultradent) and sealed with temporary glass ionomer cement (FMG Dental Products, Joinville, Brazil). The intracanal calcium hydroxide medication was replaced 3 times at 15-day intervals.

The canal was filled via the lateral and vertical condensation technique using gutta-percha cones (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and bioceramic endodontic cement (MTA Fillapex, Ângelus, Londrina, Brazil). The tooth was then sealed with glass ionomer cement (FMG Dental Products, Joinville, Brazil) (Figure 1C).

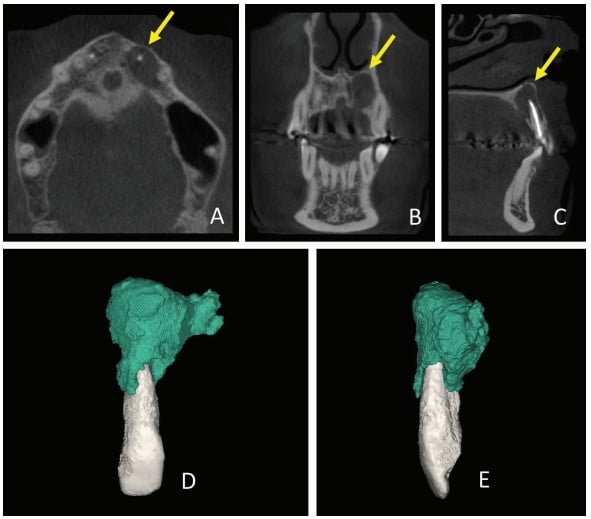

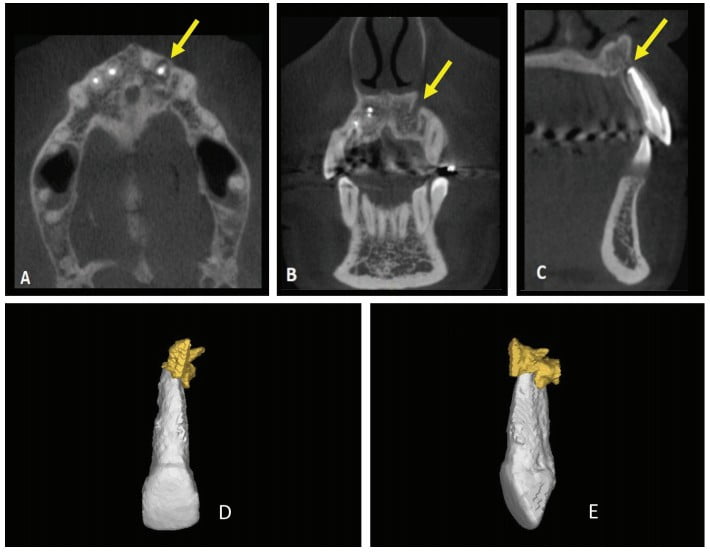

Thirty days after these procedures, the fistula reappeared in the palatal region. A cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) was acquired (Gendex CB-500 CBCT unit, Gendex Dental Systems) and showed rupturing of the palatal bone. A 3D reconstruction was performed using Mimics software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) in order to calculate the volume of the lesion for further comparison. The initial volume was 666.65 mm3 (Figure 2).

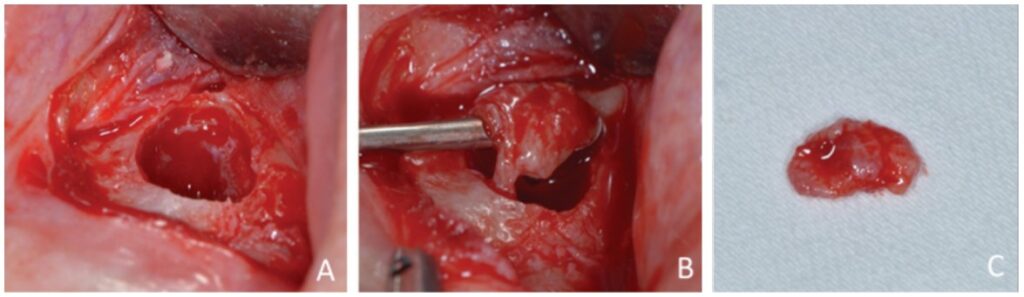

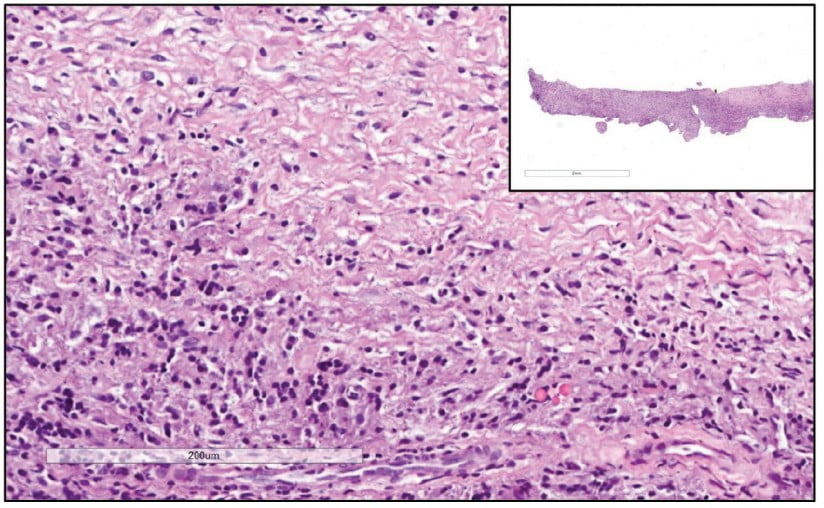

Prior to surgery, antibiotic prophylaxis, antisepsis, oral cavity asepsis, and local anesthesia were performed. Then a flap was opened using a No. 15 scalpel (Advantive Wuxi Xinda Medical Device Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China) to create a horizontal incision with small curves in the gingiva 3.0 mm from the gingival sulcus and complemented by two vertical incisions above the left upper incisors (Ochsenbein – Luebke flap).5 The tissue was broken down and the flap removed using a Molt periosteal elevator (SS White Duflex, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). The osteotomy used to access the apex of tooth No. 22 was performed with a 6-blade surgical carbide bur No. 702 (KaVo Kerr, Joinville, Brazil) at high rotation and with abundant saline solution irrigation (Figure 3A). After the osteotomy, the lesion was removed using a Lucas Curette (SS White Duflex, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) (Figure 3B) and stored in a closed container with 1% formaldehyde. Subsequent histopathological examinations identified the lesion as a periapical granuloma (Figures 3C and 4).

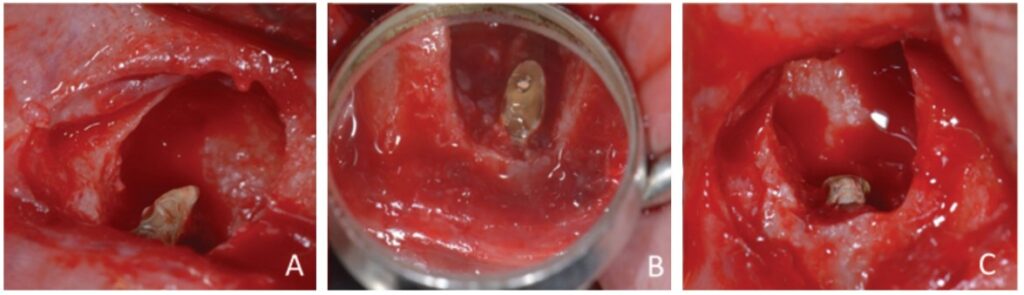

The apicectomy was performed by removing 3.0 mm from the apical portion of the root using a 6-blade surgical carbide bur no. 702 (KaVo Kerr, Chapecó Saguaçu – Joinville, Brazil) at high rotation and at a 45° angle (Figure 5).

The retrofill was performed with a mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) cement (Ângelus Indústria de Produtos Odontológicos S/A, Paraná, Brazil) and an applicator (MTA) (Ângelus Indústria de Produtos Odontológicos S/A, Londrina, Brazil). The opening was sutured with 5.0 absorbable thread (ETHICON – Johnson & Johnson). Periapical digital radiographs were acquired before (Figure 6A) and after surgery (Figure 6B).

The canal entrance was restored with glass ionomer (FMG Dental products, Joinville, SC, Brazil), while the coronary chamber was restored with A3 composite resin (3M). After 24 months, the patient was reevaluated via clinical exams, radiographs, CBCT, and a new 3D reconstruction (Figure 7).

The results of these evaluations were satisfactory and showed an absence of fistulous lesion pain and a significant decrease in lesion volume from 666.65 mm³ to 46.94 mm³, suggesting periapical tissue repair.

Discussion

Unsuccessful endodontic treatment is evidenced by a persistence of signs and symptoms that are caused by microorganisms. These may become resistant to chemical-mechanical processes and intracanal medication, thereby persisting, spreading to the canal and periapical tissue, and perpetuating infection.4,6

Endodontic bacteria cause apical periodontitis, which is characterized by inflammation of periapical tissue, and triggers acute or chronic pathologies, resorption of periapical bone, and affects root surfaces.7-10 Resistant apical periodontitis reduces treatment predictability and indicates that the permanence of bacteria in intraradicular and periapical tissues may cause refractory or recurrent infections.11

The presence of a periapical lesion that is caused by resistant microorganisms in the periapical region and attendant symptoms are fundamental indicators of treatment failure and characterize the need for new management strategies.3,12

Conventional retreatment is the first choice for dealing with unsuccessful endodontic treatments. However, when microorganisms in apical and periapical areas cannot be contained via coronary access, endodontic microsurgery can be used as a complementary therapy.5 The goal of endodontic surgery is to isolate the root canal and prevent bacterial contamination of apical and periapical tissues, thereby stimulating healing. This surgery is recommended for teeth that show persistent failure after treatment and endodontic retreatment.13

In the present clinical case, surgery was chosen due to persistent infection after satisfactory endodontic treatment as well as the persistent fistula associated with extraradicular infection and adhesion of apical microorganisms and bacteria to the root surface and within the inflammatory lesion.14,15 Failure in endodontic treatments are caused by not only technical issues but also microbiological ones since extraradicular colonies may persist even after root canal cleaning.15

Planning endodontic surgery depends on quality complementary exams that precisely show the size and extent of an apical lesion, its relationship with adjacent anatomical roots and structures, and the degree of bone involvement.16,17 Periapical radiographs are of limited value in diagnosing periapical pathologies since they offer only two-dimensional images of three-dimensional structures.18 CBCT, however, shows three-dimensional relationships among structures and provides accurate images of bone and dental tissues that can be used to diagnose alterations and pathologies in three planes: axial, coronal, and sagittal.18.19

CBCT was used in the present case to evaluate the relationship of the periapical lesion to adjacent structures and tooth No. 22, to show the extent and volume of the lesion, and to demonstrate that the lesion had already caused the lingual rupture of the cortical bone.

In the subsequent surgery, enucleation of the lesion and apicectomy were performed due to the extent and recurrence of the fistulous lesion. Enucleation was proposed to eliminate microbial agents that would have been inaccessible to conventional endodontic therapy. The goal of the apicectomy was to remove bacteria and other irritating factors from the apical region and to block microorganisms in the periapical tissues from reentering the canal, thereby stimulating healing.20 The success rate of preparing, surgically removing, and sealing the apex ranges from 88% to 94%.21

A histopathological examination showed that the lesion was composed of dense, unmodified, moderately cellularized, and vascularized connective tissue permeated by mononuclear inflammatory cells (lymphohistio-plasmacytes). No epithelial (cystic) lining or other significant histopathological elements were found. These findings and the clinical radiographic information from the case led to a diagnosis of periapical granuloma. A periapical granuloma results from the transformation of periapical tissues into granulation tissue due to chronic inflammation. Imaging exams show this tissue as a delimited, but not completely and well-defined radiolucent lesion. The pathology develops from the body’s initial attempt to promote scarring and healing.22

The tooth was retrofilled with MTA, which is biocompatible and can induce dentinogenesis, cementogenesis, and osteogenesis. MTA is also alkaline, which increases its antimicrobial potential and promotes effective marginal sealing that in turn prevents infiltration.23

A follow-up clinical exam showed absence of pain, swelling, and fistula, indicating elimination of the infection and repair of the periapical tissue. Despite the success of the procedure, a small radiolucent area may remain, which, like an “apical scar,” is asymptomatic and not pathological.24

Conclusion

We found that endodontic surgery with apicectomy and retrofilling procedures combined with endodontic therapy is a viable and effective option for treating a tooth with extensive and chronic periapical lesion.

Dr. Jorge Alberdi discusses surgical retreatment and non-surgical treatment for tooth conservation in his article “Endodontic retreatment: a conservative and predictable therapy.” Read it here: https://endopracticeus.com/endodontic-retreatment-a-conservative-and-predictable-therapy/

- Türker SA, Uzunoğlu E, Aslan MH. Evaluation of apically extruded bacteria associated with different nickel-titanium systems. J Endod. 2015;41(6):953-955.

- Lacerda MFLS, Marceliano-Alves MF, Pérez AR, et al. Cleaning and Shaping Oval Canals with 3 Instrumentation Systems: A Correlative Micro-computed Tomographic and Histologic Study. J Endod. 2017;43(11):1878-1884.

- Chércoles-Ruiz A, Sánchez-Torres A, Gay-Escoda C. Endodontics, Endodontic Retreatment, and Apical Surgery Versus Tooth Extraction and Implant Placement: A Systematic Review. J Endod. 2017;43(5):679-686.

- Kang M, In Jung H, Song M, Kim SY, Kim HC, Kim E. Outcome of nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic microsurgery: a meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19(3):569-582.

- Del Fabbro M, Corbella S, Sequeira-Byron P, et al. Endodontic procedures for retreatment of periapical lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10(10):CD005511.

- George R. Nonsurgical retreatment vs. endodontic microsurgery: assessing success. Evid Based Dent. 2015;16(3):82-83.

- Zehnder M, Rechenberg DK, Thurnheer T, Lüthi-Schaller H, Belibasakis GN. FISHing for gutta-percha-adhered biofilms in purulent post-treatment apical periodontitis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2017;32(3):226-235.

- De Rossi A, Rocha LB, Rossi MA. Interferon-gamma, interleukin-10, Intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and chemokine receptor 5, but not interleukin-4, attenuate the development of periapical lesions. J Endod. 2008;34(1):31-38.

- Nair PN. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J. 2006;39(4):249-281.

- Aw V. Discuss the role of microorganisms in the aetiology and pathogenesis of periapical disease. Aust Endod J. 2016;42(2):53-59.

- Siqueira JF, Rôças IN, Debelian GJ, et al. Profiling of root canal bacterial communities associated with chronic apical periodontitis from Brazilian and Norwegian subjects. J Endod. 2008;34(12):1457-1461.

- Kamburoğlu K, Yılmaz F, Gulsahi K, Gulen O, Gulsahi A. Change in Periapical Lesion and Adjacent Mucosal Thickening Dimensions One Year after Endodontic Treatment: Volumetric Cone-beam Computed Tomography Assessment. J Endod. 2017;43(2):218-24.

- Comparin D, Moreira EJL, Souza EM, et al. Postoperative Pain after Endodontic Retreatment Using Rotary or Reciprocating Instruments: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Endod. 2017;43(7):1084-1088.

- Ricucci D, Siqueira JF, Lopes WS, Vieira AR, Rôças IN. Extraradicular infection as the cause of persistent symptoms: a case series. J Endod. 2015;41(2):265-273.

- Sousa BC, Gomes FA, Ferreira CM, et al. Persistent extra-radicular bacterial biofilm in endodontically treated human teeth: scanning electron microscopy analysis after apical surgery. Microsc Res Tech. 2017;80(6):662-667.

- Patel S, Dawood A, Ford TP, Whaites E. The potential applications of cone beam computed tomography in the management of endodontic problems. Int Endod J. 2007;40(10):818-830.

- Tsurumachi T, Honda K. A new cone beam computerized tomography system for use in endodontic surgery. Int Endod J. 2007;40(3):224-232.

- Verner FS, D’Addazio PS, Campos CN, et al. Influence of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography filters on diagnosis of simulated endodontic complications. Int Endod J. 2017;50(11):1089-1096.

- Estrela C, Bueno MR, Azevedo BC, Azevedo JR, Pécora JD. A new periapical index based on cone beam computed tomography. J Endod. 2008;34(11):1325-1331.

- Wang J, Jiang Y, Chen W, Zhu C, Liang J. Bacterial flora and extraradicular biofilm associated with the apical segment of teeth with post-treatment apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2012;38(7):954-959.

- Setzer FC, Kohli MR, Shah SB, Karabucak B, Kim S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature—Part 2: Comparison of endodontic microsurgical techniques with and without the use of higher magnification. J Endod. 2012;38(1):1-10.

- Holland R, Filho JA, de Souza V, et al. Mineral trioxide aggregate repair of lateral root perforations. J Endod. 2001;27(4):281-284.

- Juerchott A, Pfefferle T, Flechtenmacher C, Mente J, Bendszus M, Heiland S, et al. Differentiation of periapical granulomas and cysts by using dental MRI: a pilot study. Int J Oral Sci. 2018;10(2):17.

- Schulz M, von Arx T, Altermatt HJ, Bosshardt D. Histology of periapical lesions obtained during apical surgery. J Endod. 2009;35(5):634-642.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..