Dr. Cameron Howard discusses the importance of CBCT in endodontic diagnosis

Meet Dr. Howard

Cameron Howard always knew he wanted to go into dentistry. Even in kindergarten, he was drawing pictures of teeth. As he grew older, the diagnosis of a congenitally missing tooth No. 10 in his own dentition put him in close contact with nearly every dental specialty: orthodontics, prosthodontics, and periodontics. Ironically, it was the specialty that Howard hadn’t experienced during his youth that ultimately became his passion: endodontics.

After graduating from the University of Kentucky College of Dentistry (UKCD) as class president in 2008, Dr. Howard completed his endodontic residency at Nova Southeastern University (NSU), Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. It was at NSU that his fascination for digital dentistry grew. While at UKCD, he dealt with standard film, dark rooms, and constantly jammed/clogged film processors. At NSU, however, he was informed that its program was completely digital, and that he would be furnished with his own laptop and digital sensor as part of his training. “I was excited to better my clinical experience. The world of digital radiography blew my mind. The image clarity, the speed of processing, and the ease of use were astonishing — I knew there was no going back.”

Dr. Howard spent the first 5 years of his career in corporate dentistry in Tampa, Florida, but when he moved back home to the Atlanta metro area in 2014, he opened his own fully digital practice. He decided to “shop local” and worked with Carestream Dental — which has a large office in Atlanta — to supply his operatory with RVG digital intraoral sensors. However, Dr. Howard was hesitant to install a cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) system for all the typical reasons doctors give: “It must be expensive.” “I’ve been working without one for so long. Why would I need it now?”

Just 6 months into practicing in his new office, however, Dr. Howard’s line of thinking began to shift. As a member of TDO, he started seeing amazing cases posted on its clinical forum. Many of the cases shown were diagnosed, aided, treated, and monitored through CBCT technology. It was then that Dr. Howard determined he wanted to take the next step in his office. “I desired to give the best to my patients. In my opinion, practicing with CBCT has become the new standard of care.” After thorough research of many rival CBCT manufacturers, Dr. Howard returned to Carestream Dental for a CS 8100 3D system. The unit has been in place for over 2½ years now, and according to him, it has completely changed the way he practices and how he approaches patients.

“Meet Dr. Howard” was provided by Carestream Dental.

My assistants joke that every single day, I say, “I love my cone beam,” and it’s true. Of course, not all cases require CBCT imaging, and all imaging requiring radiation should be used with care — some days I only take two or three scans as needed, and other days I take eight. However, a clear pattern of the kinds of cases CBCT can aid in has emerged: difficult diagnoses, retreats, trauma, unusual/difficult anatomy, sinus involvement, detecting accessory canals, evaluation of separated files, and resorption.

Although CBCT has proven to be a useful tool for diagnosis and treatment of any number of endodontic issues, resorption in particular stands out. Initial clinical exams or 2D radiographs may hint at resorption; however, the question of diagnosis of internal versus external resorption and the extent of each remain. If external resorption is suspected, clinicians may go so far as to flap the gingiva with the hope of finding it, but there’s no guarantee once in surgery they can properly evaluate the extent, size, and proximity of resorption to pulpal tissues. Two-dimensional imaging can only hint at perforation from the mesial-to-distal direction but doesn’t give a clear view of the lingual-to-buccal resorption presence/extent. With CBCT, however, the location, extent, and proximity of resorption to vital anatomy, especially pulp and crestal bone, are easily identifiable. Plus, it provides guidance for how to proceed with treatment.

From simply confirming resorption to much more complicated cases, the following are just a few examples of how CBCT can aid endodontists in resorption cases.

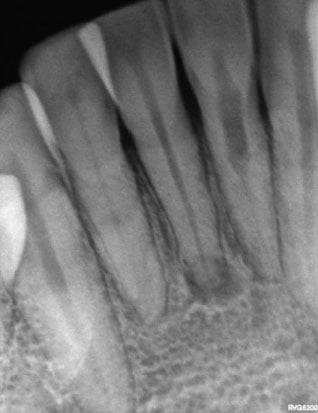

Figure 1: Case 1 pre-op 2D radiograph

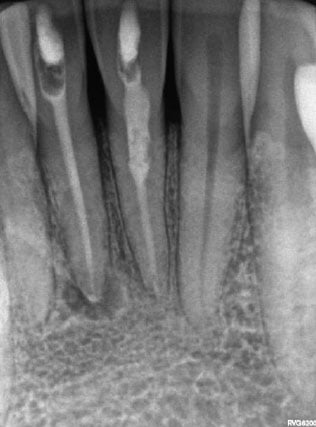

Figure 2: Case 1 other office pre-op 2D radiograph

Case 1: internal resorption

A 54-year-old female with a history of trauma presented with pain and abscess on tooth No. 25 that was causing trouble chewing. Though the 2D X-ray showed both a resorptive defect on tooth No. 24 and an abscess on tooth No. 25 (Figures 1 and 2), it was difficult to tell the extent of the internal resorption on tooth No. 24 from a buccal-to-lingual orientation. The defect appeared large, but was there buccal or lingual perforation?

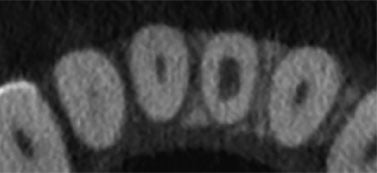

Fortunately, the CS 8100 3D revealed the resorption was encompassed in the canal in all directions (Figures 3-5), and I felt confident that RCT for tooth Nos. 24 and 25 could resolve the patient’s problems, and a two-step approach using Ca(OH)2 was utilized (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 3: Case 1 axial CBCT slice

Figure 4: Case 1 sagittal CBCT slice

Figure 5: Case 1 coronal CBCT slice

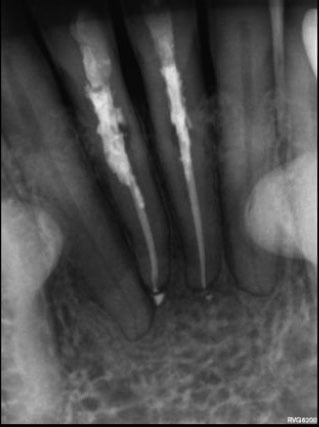

Figure 6: Case 1 Ca(OH)2 pack

Figure 7: Case 1 post-op 2D radiograph

Case 2: external resorption

A 68-year-old female was referred to my practice after her general practitioner “saw something” he couldn’t identify. The patient was asymptomatic and uncertain why she had been referred. After the clinical exam, external resorption was suspected. However, the patient was skeptical of the two-dimensional radiographs (Figure 8), which revealed very little to be concerned about, and she was hesitant to accept treatment.

However, the CS 8100 3D undoubtedly revealed external resorption (Figures 9 and 10). The scan also demonstrated a lingual orientation of cervical external resorption. At the consultation, I was able to clearly show the patient the resorption and offer treatment recommendations.

The case evolved from the GP’s very vague diagnosis of seeing “something” to actually requiring endodontic and perio-dontic treatment. The patient was referred to a periodontist who flapped the lingual gingiva and removed the resorptive defect. It was then patched with Geristore® (Figure 11). Due to pulpal blanching noted by the periodontist, prophylactic root canal therapy was performed in my practice (Figure 12), and the core was subsequently placed by the general dentist.

In addition to demonstrating CBCT’s usefulness in diagnosing external resorption, this case is an excellent example of how the digital file format of CBCT scans streamlines the process of collaborating across multi-specialties and working with referrals.

Figure 8: Case 2 2D radiograph

Figure 9: Case 2 sagittal CBCT slice

Figure 10: Case 2 axial CBCT slice

Figure 11: Case 2 pre-op after lingual period defect repair

Figure 12: Case 2 post-op 2D image

Case 3: mystery diagnosis

A 50-year-old female presented with pain in the upper right quadrant. She was positive it was one of the back two molars, and although the patient had a deep perio pocket near the posterior maxilla, the entire area was tender to both percussion and palpitation. Probing did not give me the confidence to make a diagnosis. The patient’s general dentist was questioning a possible missed MB2 on tooth No. 3 (as we’re always looking for four canals obturated) as well as a possible missed third/fourth canal in tooth No. 2 (only two canals obturated) (Figures 13 and 14).

However, the CS 8100 3D scan revealed a very large resorptive defect and extreme bone loss present with tooth No. 2 (Figures 15 and 16). The case, which originally was scheduled to be a retreat, was modified to require extraction, bone grafting, and an implant. Therefore, CBCT helps endodontists choose the best treatment for their patients, even if it’s not endodontic treatment.

Figure 13: Case 3 pre-op PA

Figure 14: Case 3 pre-op bitewing

Figure 15: Case 3 axial CBCT slice

Figure 16: Case 3 sagittal CBCT slice

Case 4: “If it were your mother’s tooth, what would you do?”

When it comes to case acceptance, almost all doctors have been asked, “If it were your (or your mother’s) tooth, what would you do?” Many patients find comfort knowing that treatment rendered is what a doctor’s loved ones would also receive. That hypothetical question became all too real when my own mother presented for treatment in June 2016.

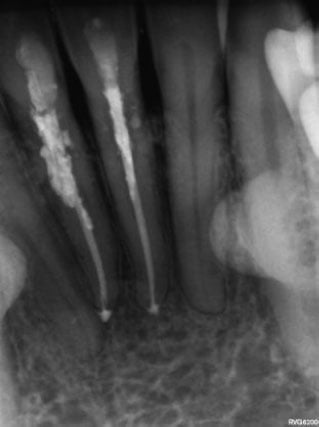

My mother had a history of trauma from when she was accidentally hit in the mouth with a tennis racket years ago — “goofing around” with my dad gone terribly wrong. During a visit to her GP, PAs of the lower anteriors hinted at the need for endodontic treatment, so she immediately came to me. Because the GP’s PAs were not of the same diagnostic quality as my own, new radiographs were taken (Figure 17). Not only was small internal resorption on tooth No. 30 also found, but extensive root resorption on teeth Nos. 24 and 25 initially had me think that these teeth are hopeless and that we’ll have to pull them and do implants.

Then a CS 8100 3D scan was performed, and I was able to see the amount of resorption in the sagittal, coronal, and axial orientation; fortunately, it had not perforated the planes of space (Figures 18 and 19).

It was decided to monitor tooth No. 30 and to initiate treatment, using Ca(OH)2, for teeth Nos. 24 and 25 (Figure 20). My mother was recalled 3 weeks later to fill the canal (Figure 21). She returned for a 1-year checkup in the summer of 2017. The root canals were deemed successful, and no further resorption was noted (Figure 22). Furthermore, tooth No. 30 had no changes in its resorptive pattern. Having a CBCT scan helps monitor the extent of changes in the size and amount of resorption in a patient’s tooth over time. Also, CBCT helped show me when not to perform treatment, as I was confident I could successfully monitor tooth No. 30 and perform a less aggressive treatment on my own mother.

When I first opened my practice, I didn’t see the point of having an in-office CBCT system. However, it didn’t take long for me to change my thinking. Much like the switch from film and processors to digital sensors, there’s no going back for me in regards to CBCT. Not only has using it changed my clinical thinking and provided the opportunity to be more conservative, but it has also positively changed the results of my treatment planning. I trust my CBCT system for my own mother’s dental care, and as I say every day, “I love my cone beam.”

Figure 17: Case 4 pre-op

Figure 18: Case 4 sagittal CBCT slice No. 24

Figure 19: Case 4 sagittal CBCT slice No. 25

Figure 20: Case 4 Ca(OH)2 pack

Figure 21: Case 4 post-op

Figure 22: Case 4 one-year recall

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..