Drs. Karl Woodmansey and Yogesh Patel illustrate their interventions to retain a mandibular first molar

This case report illustrates extreme endodontic interventions to retain a mandibular first molar. At many decision points during the treatment of this tooth, dental implants could have been considered as an appropriate treatment plan. Although dental implants can provide functional replacements for lost teeth, this patient desired to retain her natural tooth at all costs — and to date, she has.

This tooth was treated by two endodontic residents (KW and YP) at the Texas A&M University/Baylor College of Dentistry in Dallas, Texas. All treatment was performed prior to widespread availability of cone beam CT imaging.

Case report

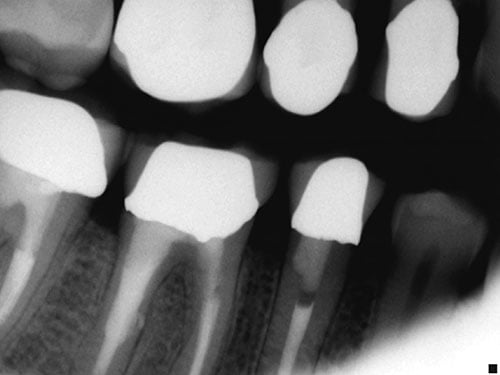

A 40-year-old black female in good general health with no medications and no allergies initially presented to the Baylor College of Dentistry Graduate Endodontics Department in January 2004 with a chief complaint of pain on biting with tooth No. 30 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

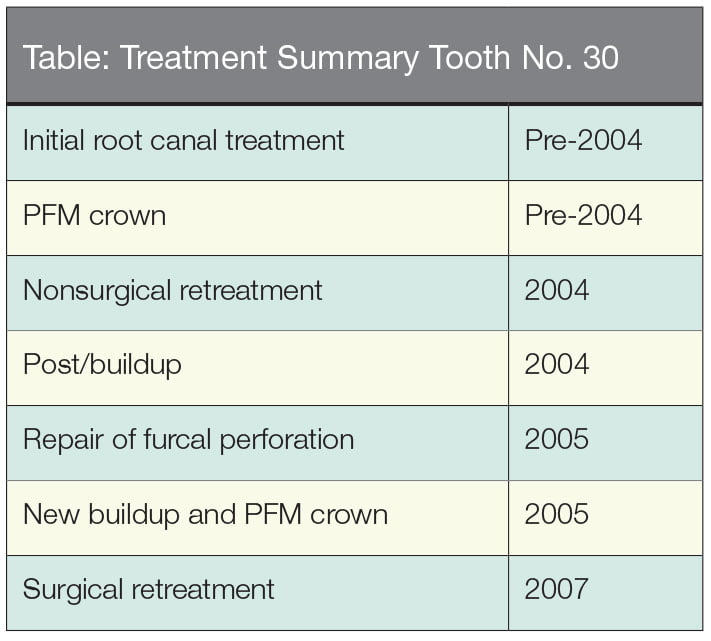

Figure 2

Figure 3

The patient reported that the previous root canal treatment was “many years old.” A periapical radiolucency was noted at the distal root apex. The mesial canals appeared obturated with silver points (Figure 2).

Tooth No. 30 was diagnosed as previously treated with subacute periradicular periodontitis. Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment was completed in February 2004 (final radiograph not available).

In February 2004, a dental student placed a Brasseler post (Brasseler USA®, Savannah, Georgia) and a resin buildup (final radiograph not available).

In December 2004, the patient returned to graduate endodontics and reported spontaneous aching and pain on biting with tooth No. 30. The radiograph documents a large parallel-post cemented in the distal canal. The post appears to “strip-perforate” the furcation wall of the distal root with cement extrusion and an associated furcal radiolucency. The distal root periapex demonstrates some radiographic healing (Figure 3).

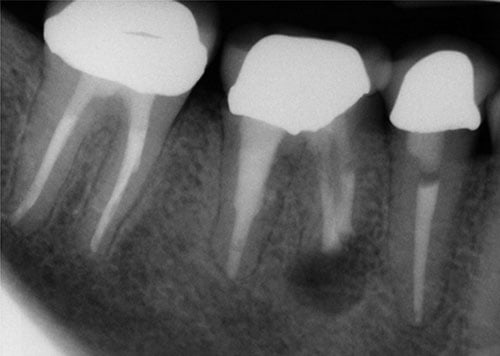

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

In January 2005, the post was removed, and a furcal perforation of the distal root was confirmed. The apical segment was retreated with gutta percha; the perforation was internally repaired with mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) (ProRoot® MTA, Dentsply Sirona, York, Pennsylvania); and the coronal portion of the canal was obturated with MTA. The mesial canals were not retreated. A new buildup/access-repair restoration was placed. In the posttreatment radiographs, the perforation repair is evident as is the residual thinness of the root walls (Figure 4).

This August 2005 radiograph illustrates partial healing of the distal root’s apical and furcal areas (Figure 5).

In September 2005, a new PFM crown was cemented (radiograph not available).

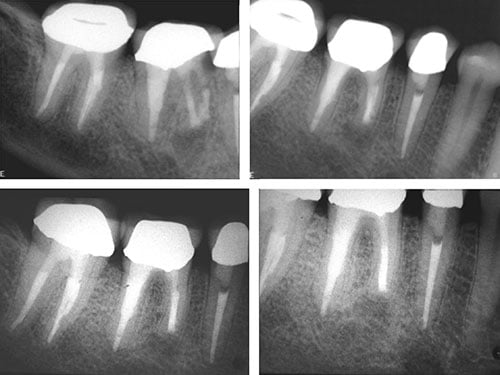

Figure 6

Figure 7

In November 2007, the patient returned reporting vague pain in the tooth No. 30 area for the past 2 months, with pain on chewing and occasionally requiring Tylenol® for pain relief. Her chief complaint was, “This tooth is hurting again.” A photograph documented the quadrant dentition and restorations (Figure 6).

A bitewing radiograph demonstrated complete healing of the furcation perforation (Figure 7).

Figure 8

Figure 9

A periapical radiograph (November 2007) demonstrated complete healing of the distal periapex, but now a periapical radiolucency was present at the apex of the mesial root (Figure 8).

Although nonsurgical endodontic retreatment was considered as a possible treatment option, the patient was offered extraction/implant or endodontic surgery as treatment options. She elected endodontic surgery, desiring to retain her natural tooth. Surgical root canal treatment, root-end resection, and root-end filling (apicoectomy) of the mesial root were performed in December 2007.

This photo shows the osteotomy and resection of the apex of the mesial root. The PDL space and inter-canal isthmus are stained with methylene blue. This isthmus illustrates the difficulty of debriding, disinfecting, and obturating complex canal anatomy with nonsurgical endodontic treatment. Here, with surgical access, the treating endodontist can directly address the bacterial biofilm residing within the isthmus space (Figure 9).

Figure 10

Figure 11

This is the histopathologic specimen removed from the apex, diagnosed by the Baylor College of Dentistry Oral Pathology Service as a dental granuloma. The specimen includes infiltrates of plasma cells and lymphocytes. The brown material is extruded sealer (Figure 10).

This photo shows the root-end MTA filling (White ProRoot® MTA, Dentsply Sirona, York, Pennsylvania) condensed into the preparation, including the isthmus (Figure 11).

Figure 12

Figure 13

These periapical radiographs show the root-end filling immediately post-surgery (December 2007) (Figures 12 and 13).

Figure 14

Figure 15

This radiograph from July 2009 documents good healing of the apical defect with re-formation of the PDL space and lamina dura. Some altered trabeculation remains. The patient is asymptomatic and has retained her natural dentition (Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 16

Figure 17

The patient was asymptomatic at her August 2010 re-evaluation visit. This clinical photo documents the condition of tooth No. 30 at that time (Figure 16).

Radiographs from the August 2010 reevaluation demonstrate continued/complete healing of the apical defect with re-formation of the PDL space and lamina dura. Some altered trabeculation remains (Figure 17).

Acknowledgments

Drs. Woodmansey and Patel wish to acknowledge the skilled faculty who guided their treatment of this patient.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..