Drs. Michael Ford and Gerald Glickman show how GentleWave provides cleaning and obturation that is superior to conventional methods.

Drs. Michael W. Ford and Gerald N. Glickman discuss a promising technique to manage mandibular molar middle mesial anatomy and other complex anatomy

Abstract

Thorough cleaning and disinfection of the root canal system is the prerequisite for successful endodontic treatment. Hidden anatomy within the mesial roots of mandibular molars poses a special challenge to cleaning. This case series presents five treatments where the middle mesial anatomy of mandibular molars was accessed and identified only after multisonic irrigant cleaning and subsequent obturation. Follow-up radiographs demonstrated healing of the periapical lesions (where present). Multiple cases of uninstrumented, but obturated middle mesial anatomy have not been previously reported.

Introduction

Endodontic success depends on adequate cleaning and disinfection of the root canal system. In turn, a thorough understanding of canal morphology is fundamental to endodontic therapy.1 Otherwise, pulp tissue, debris, biofilm, and/or microorganisms may remain and contribute to a milieu favoring persistent inflammation.2 Mandibular first molars are among the most commonly treated teeth in endodontic therapy.3,4 Therefore, it is incumbent upon the clinician to apply an appropriate treatment strategy for maximum cleaning and disinfection efficacy.

The following case series describes the use of a new multisonic approach that may help detect and clean middle mesial anatomy. This multisonic approach, known as the GentleWave® System (Sonendo, Inc.) consists of a console and a Procedure Instrument (PI). It has been developed as a neoteric approach for cleaning and disinfection of the root canal system in a way that appears to be superior to conventional methods.19-22

Case series

Similarities in all cases

For brevity, please note that all case treatments would demonstrate the following: Treatment options were discussed with the patient, and informed consent was obtained. All patients received local anesthetic followed by the placement of a dental dam. A dental operating microscope (DOM) was used for the entirety of the procedures. Endodontic access, patency, and working lengths using an electronic apex locator (EAL) were established. The use of ultrasonics via Enac OE-505™ (Osada Electric Company) was used in an attempt to locate any middle mesial anatomy but was unsuccessful. Debridement and disinfection of the root canal systems were completed using the GentleWave Procedure.10 An operator-formed platform opening into the endodontic access was created to form a fluid-tight seal on the tooth. The PI was then placed onto the platform, and the seal was confirmed during the GentleWave System’s leakage test with a multisonic activation of distilled water for 30 seconds. The teeth were treated using the extended GentleWave Procedure setting with 3% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes, distilled water for 30 seconds, 8% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for 2 minutes, and finally rinsed by the GentleWave System with distilled water for 15 seconds. The canals were dried with absorbent paper points and obturated using a warm vertical compaction technique with gutta percha and AH Plus® sealer (Dentsply Sirona) for a final seal. Unless contraindicated, three ibuprofen (800mg; QID PRN) were given to each patient posttreatment with a postoperative instruction sheet and after-hours emergency contact information.

Case 1

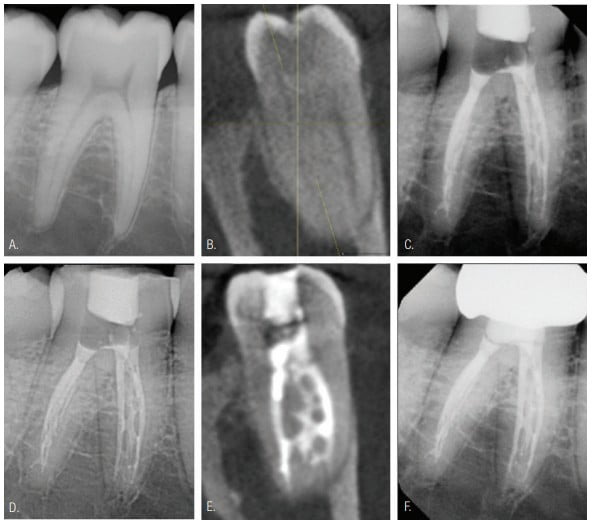

A 27-year-old female with a history of hypertension and hypothyroidism presented to the clinic complaining of localized tooth pain. Upon presentation, the patient reported a pain level of 7 on the 11-point verbal numeric rating scale (VNRS).9 Based on the history of symptoms, clinical, and radiographic examination, tooth No. 30 was given a pulpal diagnosis of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis and a periradicular diagnosis of symptomatic apical periodontitis, secondary to Cracked Tooth Syndrome (CTS) (Figures 1A and 1B).

Three distinct canals were identified: mesiobuccal, mesiolingual, and distal canals. An EdgeFile® X7 (EdgeEndo™) size 20/.04 was used to shape all three canals and create a fluid and obturation path. Debridement and disinfection of the root canal system were completed using the GentleWave Procedure as previously described. Upon radiographic review, a distinct middle mesial anatomical configuration between the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual canals was visible. It spanned from the coronal third to the apical third and repeatedly connected and disconnected with the mesial canals (Figures 1C and 1D; CBCT Figure 1E). The patient was contacted 1 day postoperatively and reported a pain level of 0 on the VNRS and had taken only the first 800 mg Motrin (taken in our office). At the 4-month recall, it was noted that the final restoration had been placed, and the tooth was healing within normal limits (Figure 1F). The 18-month clinical and radiographic follow-up revealed the tooth was clinically asymptomatic, and the patient was pain-free.

Case 2

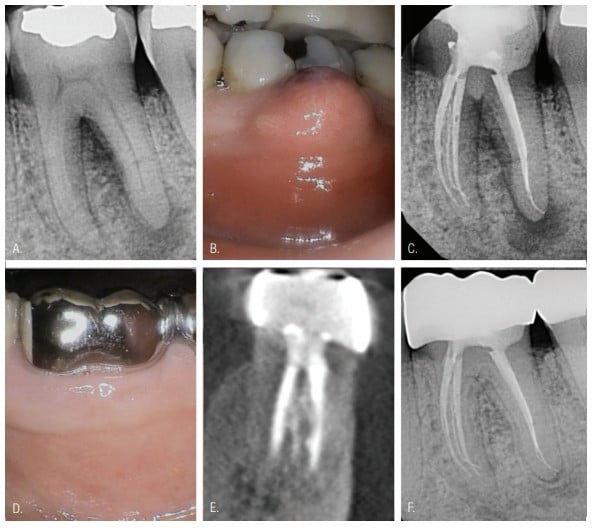

A 51-year-old male with a history of hypertension presented to the clinic complaining of swelling at the gingival margin and tooth pain with a pain rating of 10 on the VNRS. Based on the history of symptoms, clinical, and radiographic examination, a pulpal diagnosis of pulpal necrosis and a periradicular diagnosis of chronic apical abscess were made for tooth No. 19 (Figure 2A).

After receiving local anesthesia, periodontal probing confirmed there were no additional periodontal concerns (Figure 2B). Four distinct canals were identified: mesiobuccal, mesiolingual, distobuccal, and distolingual. Shaping up to size EdgeFile X7 20/.04 was used in all four canals to create a fluid and obturation path. Debridement and disinfection of the root canal system were completed using the GentleWave Procedure as previously described. Posttreatment radiographs revealed a distinct and separate uninstrumented middle mesial canal commencing in the coronal third with a distinct and separate exit within the apical third. In addition, an isthmus connecting the middle mesial and mesiolingual canals was visible (Figure 2C). The patient was contacted 4 days postoperatively and reported a pain level of 0 on the VNRS. At the 3-week recall, clinical examination revealed complete healing of the sinus tract (Figure 2D). The 2-year recall indicated that the patient remained infection- and pain-free. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed furcal and periapical osseous healing, and the tooth was asymptomatic. (Figures 2E and 2F).

Case 3

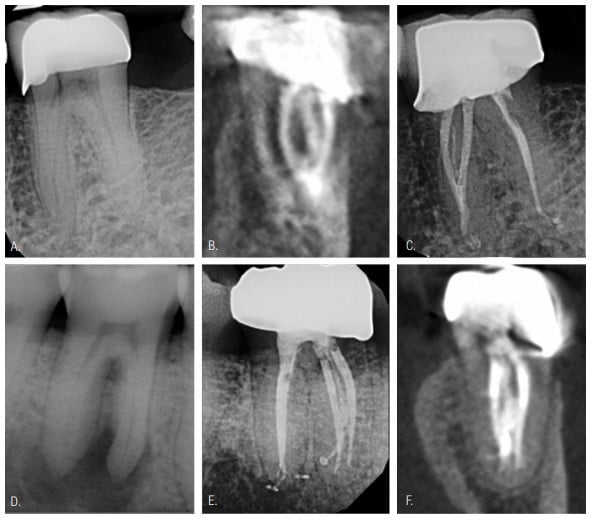

A 58-year-old female presented to the clinic with a localized tooth pain level of 6 on the VNRS. From the history of symptoms, clinical, and radiographic examination, a pulpal diagnosis of previously treated and a periradicular diagnosis of symptomatic apical periodontitis were made for tooth No. 30 (Figures 3A and 3B).

After endodontic access, the gutta percha placed during the previous root canal therapy was removed with 0.36 ml of chloroform. Debridement and disinfection of the root canal system were completed using the GentleWave Procedure as previously described. A radiograph was taken following the GentleWave Procedure to verify the removal of the previous fill. It was noted that some obturation material remained in the distal canal; however, the mesial canal appeared mostly clear (Figure 3C). Postoperative radiographs revealed a middle mesial anatomical variation visible from the coronal third of the mesiolingual and mesiobuccal canals to the apical third where it made a separate exit near the mesiolingual canal (Figure 3D). The patient was contacted 1 day postoperatively and reported a pain level of 0 on the VNRS and had discontinued use of all NSAIDs. The 7 month and one year recalls demonstrated apparent osseous healing. The tooth was clinically asymptomatic and fully functional per the patient (Figures 3E and 3F).

Case 4

An 81-year-old male with a history of hypertension presented to the clinic with localized tooth pain stating a pain level of 4 on the VNRS. From the history of symptoms, clinical, and radiographic examination, a pulpal diagnosis of symptomatic irreversible pulpitis and a periradicular diagnosis of asymptomatic apical periodontitis were made for tooth No. 19 (Figure 4A).

Four distinct canals were identified: mesiobuccal, mesiolingual, distobuccal, and distolingual. An EdgeFile X7 size 25/.04, with intermittent water irrigation was used to shape all four canals and create a fluid and obturation path. Debridement and disinfection of the root canal system were completed using the GentleWave Procedure as previously described. Upon radiographic review, separate and distinct uninstrumented middle mesial anatomy was visible between the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual canals. It commenced within the coronal third before joining all three canals at an isthmus within the apical third and converging to one distinct apical exit (Figure 4B). The patient was contacted 1 day postoperatively and reported a pain level of 0 on the VNRS and had discontinued all NSAIDs. The 4-month recall indicated that the patient remained pain-free. The 14-month clinical and radiographic exam revealed that the tooth was asymptomatic and appeared radiographically normal (Figure 4C).

Case 5

A 54-year-old male with a history of angioplasty presented to the clinic with a chief complaint of pain when biting that rated an 8 on the VNRS. From the history of symptoms, clinical, and radiographic examination, a pulpal diagnosis of pulpal necrosis and a periradicular diagnosis of symptomatic apical periodontitis were made for tooth No. 30 (Figure 4D).

An EdgeFile X7 size 25/.04 was used to shape all three canals — mesiobuccal, mesiolingual, and distal — to create a fluid and obturation path. The GentleWave Procedure, as previously described, was used to complete debridement and disinfection of the root canal system. The patient was contacted 1 day postoperatively and reported a pain level of 0 on the VNRS as well as having discontinued use of all NSAIDs. Upon radiographic examination, a middle mesial anatomical variation was visible from the coronal third to the apical third of the mesiolingual and mesiobuccal canals (Figure 4E). It joined with the mesiobuccal canal in the middle third before exiting in the apical third. At the 16-month recall, the patient remained asymptomatic; cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) appeared to reveal significant osseous healing, and the tooth remained clinically asymptomatic (Figure 4F).

Discussion

The presented case studies illustrate the difference between current endodontic terminology of “middle mesial canals (MMC)” as opposed to the potential, otherwise undetected, uncleaned, and unobturated presence of complex anatomy and tissue remnants between the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual canals of mandibular molars.6,8 This complex anatomy may be better termed middle mesial anatomy (MMA). As these cases demonstrate, the area apparently debrided, cleaned, and obturated was not mechanically opened with any endodontic file or by conventional ultrasonics.

Middle mesial canals in mandibular molars are currently reported as an uncommon but well-recognized anatomical phenomena.5,7,12 However, MMA can be difficult to detect, which may lead to a greater underestimation of its incidence. Cone beam computed tomography is a powerful tool to examine root canal morphology; however, the CBCT’s ability to detect MMA, in most cases, has been shown to be low.13,14 Micro-CT scans appear promising due to higher resolution but at present are not clinically feasible.13

Middle mesial canal detection requires clear visibility, specialized instruments, and extra clinician attention to avoid iatrogenic events.7 Even so, locating smaller variances of MMA would still prove difficult as it may not be confluent with the pulp chamber and thus not visibly detectable. Furthermore, morphological complexities associated with the MMC such as isthmuses, can jeopardize debridement and disinfection efficacy. In the present case series, the multisonic cleaning and debridement applied by the GentleWave Procedure, without instrumentation, allowed for obturation of the space with likely sealer only.

This case series demonstrates the ability of the GentleWave Procedure to clean complex molar anatomies. No mechanical instrumentation or further opening of the mid-mesial areas previously described was performed. It is proposed that this case series has clinically demonstrated the “hidden” existence of the MMA complexities in contrast to the somewhat risky procedure of artificially creating a mid-mesial canal through conventional endodontic therapy practices.15-18 This new approach uses multisonic technology whereby degassed fluids are delivered into the pulp chamber to clean the root canal system through negative apical pressure and the generation of a broad spectrum of acoustic waves.19-22 Prior to utilizing the GentleWave procedure, there was no radiographic or clinical evidence of MMA in these cases. Posttreatment radiographs revealed the presence of the uninstrumented MMA with various configurations (Figures 1C, 2C, 3D, 4C, and 4E) indicating that this technique and the use of the GentleWave Procedure were able to:

- Remove possible dentinal projections and pulp tissue, and provide a fluid path to the MMA present

- Sufficiently debride the natural MMA without instrumentation with subsequent obturation

While these findings cannot yet be said to be clinically significant, they do indicate that this technique may aid in debriding and cleaning the natural MMA even when not visible on pretreatment radiographs. This may reduce the need to trough the mesial pulpal groove 1 mm-2 mm, as recommended by Azim7; unfortunately, troughing is associated with significant dentin removal and procedural complications (e.g., perforations).7,16,23

The cases presented here cannot support a claim that the GentleWave Procedure can detect the MMA in all cases. Prospective studies are required to test this hypothesis. Nevertheless, this case series suggests that the GentleWave Procedure may be a promising technique to manage mandibular molar middle mesial anatomy and other complex anatomy when present. Since not all MMA is accessible, even with troughing preparations,16 incorporating new techniques such as the GentleWave Procedure into a clinician’s armamentarium to manage various and/or unique clinical scenarios may be useful in our goal of cleansing the canal system. The present findings are the first to demonstrate in vivo evidence of canal debridement in MMA using this novel procedure. With further research and clinical findings, establishing technique(s) to clean MMA and associated anastomoses, as well as other complex anatomy, may demonstrate improved patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jami Lynn Trobaugh for her thorough and comprehensive insights and administrative support.

Dr. Brian Wells looks at effective cleaning and obturation with GentleWave in his article, “Effective retreatments with the GentleWave® System.” Read it here: https://sonendo.com/media/brian-wells-endodontic-practice-us-winter-2019

- Tabassum S, Khan FR. Failure of endodontic treatment: The usual suspects. Eur J Dent. 2016;10(1):144-147.

- Nair PNR. Pathogenesis of apical periodontitis and the causes of endodontic failures. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15(6):348-381.

- Ahmed H, Sadaf De, Rahman M. Frequency and distribution of endodontically treated teeth. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19(10):605-608.

- Poorni S, Kumar R, Indira R. Canal complexity of a mandibular first molar. J Conserv Dent. 2009;12:37-40.

- Baugh D, Wallace J. Middle mesial canal of the mandibular first molar: a case report and literature review. J Endod. 2004;30(3):185-186.

- Vertucci FJ, Williams RG. Root canal anatomy of the mandibular first molar. J N J Dent Assoc. 1974;45(3):27-28.

- Azim AA, Deutsch AS, Solomon CS. Prevalence of middle mesial canals in mandibular molars after guided troughing under high magnification: An in vivo investigation. J Endod. 2015;41(2):164-168.

- Ricucci D, Siqueira JF Jr. Biofilms and apical periodontitis: Study of prevalence and association with clinical and histopathologic findings. J Endod. 2010;36(6):1277-1288.

- Mccarthy PJ, Mcclanahan S, Hodges J, Bowles WR. Frequency of localization of the painful tooth by patients presenting for an endodontic emergency. J Endod. 2010;36(5):801-805.

- Sigurdsson A, Garland RW, Le KT, Woo SM. 12-month healing rates after endodontic therapy using the novel Gentlewave System: a prospective multicenter clinical study. J Endod. 2016;42(7):1040-1048.

- D’Souza AL, Rajkumar C, Cooke J, Bulpitt CJ. Probiotics in prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhoea: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2002;324(7350):1361.

- Kottoor J, Sudha R, Velmurugan N. Middle distal canal of the mandibular first molar: a case report and literature review. Int Endod J. 2010;43(8):714-722.

- Ordinola-Zapata R, Bramante CM, Versiani MA, et al. Comparative accuracy of the clearing technique, CBCT, and micro-CT methods in studying the mesial root canal configuration of mandibular first molars. Int Endod J. 2017;50(1):90-96.

- Pawar AM, Pawar M, Kfir A, et al. Root canal morphology and variations in mandibular second molar teeth of an Indian population: an in vivo cone-beam computed tomography analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2017;21(9):2801-2809.

- Karapinar-Kazandag M, Basrani BR, Friedman S. The operating microscope enhances detection and negotiation of accessory mesial canals in mandibular molars. J Endod. 2010;36(8):1289-1294.

- Kele A, Keskin C. Detectability of middle mesial root canal orifices by troughing technique in mandibular molars: a micro–computed tomographic Study. J Endod. 2017;43(8):1329-1331.

- Bond J, Hartwell G, Donnelly J, Portell F. Clinical management of middle mesial root canals in mandibular molars. J Endod. 1988;14(6):312-314.

- Holtzmann L. Root canal treatment of a mandibular first molar with three mesial root canals. Int Endod J. 1997;30(6):422-423.

- Haapasalo M, Shen Y, Wang Z, et al. Apical pressure created during irrigation with the GentleWaveTM system compared to conventional syringe irrigation. Clin Oral Investig. 2016;20(7):1525-1534.

- Ma J, Shen Y, Yang Y, et al. In vitro study of calcium hydroxide removal from mandibular molar root canals. J Endod. 2015;41(4):553-558.

- Mohammadi Z, Jafarzadeh H, Shalavi S, Palazzi F. Recent advances in root canal disinfection: a review. Iran Endod J. 2017;12(4):402-406.

- Molina B, Glickman G, Vandrangi P, Khakpour M. Evaluation of root canal debridement of human molars using the GentleWave System. J Endod. 2015;41(10):1701-1705.

- Schäfer E, Dammaschke T. Development and sequelae of canal transportation. Endod Topics. 2006;15(1):75-90.

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..

Michael W. Ford, DDS, MS, is a private practice endodontist in Harker Heights, Texas. Dr. Ford completed his Bachelor of Science Degree from The Ohio State University and his Doctor of Dental Surgery Degree from The Ohio State University, College of Dentistry in Columbus, Ohio. Dr. Ford completed his postgraduate specialty training in endodontics with the U.S. Army, Fort Gordon, Georgia, and earned a Master’s degree in Oral Biology from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta.

Michael W. Ford, DDS, MS, is a private practice endodontist in Harker Heights, Texas. Dr. Ford completed his Bachelor of Science Degree from The Ohio State University and his Doctor of Dental Surgery Degree from The Ohio State University, College of Dentistry in Columbus, Ohio. Dr. Ford completed his postgraduate specialty training in endodontics with the U.S. Army, Fort Gordon, Georgia, and earned a Master’s degree in Oral Biology from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta. Gerald N. Glickman, DDS, MS, MBA, JD, is a Professor in the Department of Endodontics at Texas A&M University College of Dentistry in Dallas, Texas. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics (ABE) and is past President of the American Association of Endodontists, and from 2012-2013, he was President of the American Dental Education Association. Dr. Glickman is a Fellow of both the American College of Dentists and the International College of Dentists and is an associate editor for the Journal of Endodontics.

Gerald N. Glickman, DDS, MS, MBA, JD, is a Professor in the Department of Endodontics at Texas A&M University College of Dentistry in Dallas, Texas. He is a Diplomate of the American Board of Endodontics (ABE) and is past President of the American Association of Endodontists, and from 2012-2013, he was President of the American Dental Education Association. Dr. Glickman is a Fellow of both the American College of Dentists and the International College of Dentists and is an associate editor for the Journal of Endodontics.