In his second article of the series, Dr. Tony Druttman offers some tips on the often difficult subject of diagnosing endodontic problems

The diagnosis of an endodontic problem is like everything else in dentistry, sometimes very easy, sometimes impossibly difficult. We have all been in the situation where a patient has presented in pain, and it has been a considerable challenge to locate the cause.

Although pain is often the trigger for endodontic treatment, that is not always the case. Sometimes an endodontic lesion is symptomless and is only picked up from a radiograph. In other situations, the culprit may be of periodontal, occlusal, or not even of dental origin. Trying to establish a diagnosis is a bit like being a detective – get a statement and then, look at the evidence. It starts with a dental history, which will give you important clues, followed by a clinical and radiographic examination, and then, the special tests.

This article will not be an exhaustive review of diagnosis, but will cover some points that will be helpful in everyday general practice.

Pulp damage

Damage to the pulp is cumulative, so that starting from the first restoration to secondary caries to a larger restoration to a crown, the pulp is being repeatedly assaulted. In the early stages, it recovers, but as the physiological pulp space reduces with age and with the assault or insult, so the blood supply to the pulp reduces, and it becomes less able to defend itself against incoming bacteria. Think how often a perfectly symptomless tooth that you have decided to protect with a crown becomes symptomatic after you have prepared the tooth.

In the early stages of the demise of the pulp, as it becomes irreversibly inflamed, it will either produce a prolonged response to temperature, produce spontaneous episodes of pain without stimulus, or both. This is sometimes referred to as a stressed pulp. Often the pain radiates, and in a heavily filled dentition, it can be very difficult to work out which is the culprit. The radiograph may not give any indication of a problem, other than perhaps a sclerosed pulp chamber (Figure 1).

Cracked teeth

Often patients will complain of temperature sensitivity and pain on biting in the early stages of a cracked tooth. The pulp will be vital at this time, although the tooth may be irreversibly damaged. As the crack progresses, more bacteria invade the pulp space, and may become tender to percussion and show periradicular changes on a radiograph.

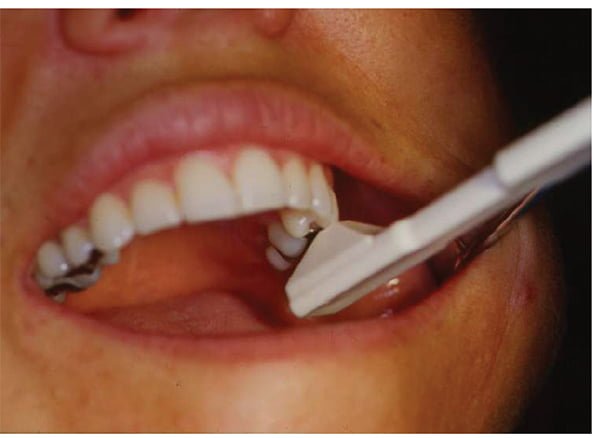

An easy way to diagnose a cracked tooth in the early stages is to use a Tooth Slooth® (Figure 2) and get the patient to bite on each cusp in turn. The pain is triggered on release, not on biting.

Root fractures

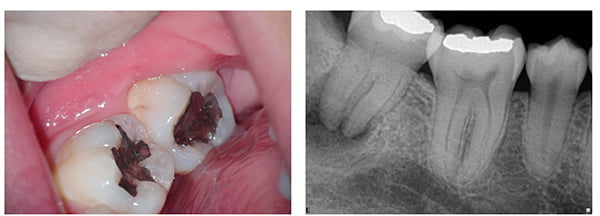

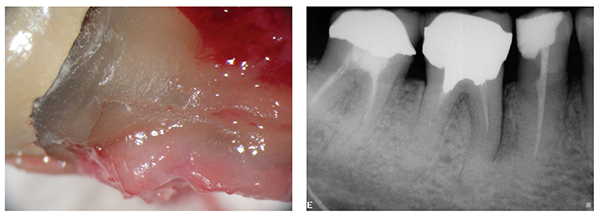

A root may crack or fracture through occlusal stresses that have propagated from the coronal tooth tissue. Conversely, it may fracture from the apical end during lateral condensation. If you use that method of obturation, you may not even be aware of using excessive force with a lateral spreader. A cracked root will cause a narrow periodontal pocket (Figure 4), which will often show on a radiograph as a J-shaped lesion (Figure 5). A tooth without a crack can have a similar radiographic appearance, but there is no pocket (Figure 6).

Endo-perio lesions

Endodontic infections can sometimes mimic periodontal disease with the development of deep pockets and considerable bone loss, particularly in furcal areas. A careful clinical examination to look for signs of cracks and a radiographic examination to look for signs of a sclerosed or damaged pulp chamber will often reveal that the cause is endodontic and not periodontal. Vitality tests should also be carried out. Endodontic treatment will often heal pockets very quickly, particularly if the lesion is not a longstanding one (Figures 7A and 7B).

Vitality tests

Electric pulp tests, and hot and cold tests are used to determine the vitality of the tooth. A vital tooth is one that has an intact blood supply, but these tests gauge the reaction of the nerve supply, not the blood supply. The C-fibers in the nerve may give a positive response even when the blood supply has been compromised or lost. The electric pulp test is not always reliable because in a multi-rooted tooth, the pulp may be dead in one canal and alive in another. In sclerosed canals, the electrical stimulus may not get through to the pulp.

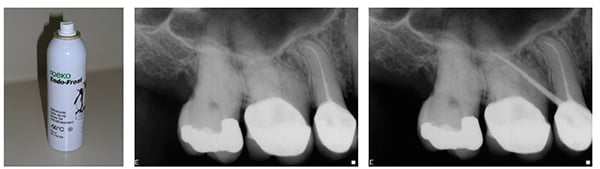

Cold tests are often more reliable, but the temperature has to be sufficiently low. Ice or ethyl chloride (-4°C) is just not cold enough; far better to use ROEKO Endo-Frost (Coltène Whaledent®), which reaches -50°C (Figure 8). When taking a history, always ask if anything triggers the pain. If the answer is either hot or cold, these can be used to help diagnose the source of the symptoms. Often the problem tooth is easy to identify, but when it is not, because of large restorations, crowns, etc., each tooth can be isolated with rubber dam and a syringe full of hot water applied to the tooth.

Draining sinus

If you see a draining sinus or fistula adjacent to a tooth, always take a radiograph with a gutta-percha point in the sinus (if it is painful, use a little local anesthetic). The sinus does not always take the shortest route out, and one can easily be caught by surprise. The case in Figures 9A and 9B was misdiagnosed as a problem with tooth No. 15. Extraction and an implant were recommended.

Summary

Hopefully these little tips are useful, and you can incorporate them into your usual diagnostic sieve. The important thing with diagnosis is to think logically.

Next issue – Radiography

Stay Relevant With Endodontic Practice US

Join our email list for CE courses and webinars, articles and more..

Endodontic specialist Tony Druttman, MSc, BChD, BSc, has extensive expertise in treating dental root canals, resolving difficult endodontic cases, and saving teethfrom being extracted. His two London, England practices, one in the West End and the other in the City of London are restricted to endodontic treatment. www.londonendo.co.uk

Endodontic specialist Tony Druttman, MSc, BChD, BSc, has extensive expertise in treating dental root canals, resolving difficult endodontic cases, and saving teethfrom being extracted. His two London, England practices, one in the West End and the other in the City of London are restricted to endodontic treatment. www.londonendo.co.uk