CE Expiration Date:

CEU (Continuing Education Unit): Credit(s)

AGD Code:

Educational aims and objectives

This clinical article aims to give protocols for the identification, diagnosis, and management of cracked teeth.

Expected outcomes

Endodontic Practice US subscribers can answer the CE questions by taking the quiz to earn 2 hours of CE from reading this article. Correctly answering the questions will demonstrate the reader can:

- Obtain an 8-point plan for tackling cracks.

- Realize some reasons for occurrence of cracks.

- Identify methods of clinical examination and investigation of cracks.

- Realize some advantages and shortcomings of imaging for detecting cracks.

- Realize several factors that could affect prognosis of cracks.

Dr. John Rhodes looks at management of cracked teeth for improving treatment outcomes and increasing the tooth’s survival rate.

Dr. John Rhodes presents another interactive, practical, and problem-solving solution in endodontics. In this issue, he looks at the identification, diagnosis, and management of cracked teeth

The survival rate of root-filled teeth at 5 years can be as high as 99%, but presence of a crack could reduce the likely survival rate by up to 10% (Sim, et al., 2016). Optimal management of cracked teeth will enhance the likelihood of long-term survival and success.

Introduction

Cracks may result from increased occlusal forces, bruxist habits, or occlusal interferences. Heavily filled teeth are weakened by the loss of tooth volume and will be more susceptible. Post-crown restorations in anterior teeth with reduced or no ferrule will have a higher risk of root fracture. Teeth can also fracture as the result of trauma, the most common presentation being an oblique fracture in anterior teeth. Cracks can be created iatrogenically during restorative procedures, for example, when removing a post or drilling with insufficient water coolant. Cracks can also be induced during apical surgery when using an ultrasonic tip with insufficient coolant or at too high power.

A crack may present while the tooth is still vital with the patient complaining of discomfort when chewing, and this is frequently accompanied by sharp pain on release. This can be accompanied by increased sensitivity to cold as the pulp becomes reversibly pulpitic. Often an individual cusp is fractured and flexing; detection can be made by careful examination using good illumination, magnification, and a simple bite test with a bite stick on the individual cusps to isolate the culprit.

Patients may present with a lost restoration or tooth that feels mobile. Post-retained anterior crowns that have de-cemented can often be associated with vertical root fracture. A lack of ferrule results in excessive stress on the root. If it fractures and flexes with occlusal forces, the cement lutes fails, and the crown becomes loose.

Visual assessment: magnification, illumination, and radiographs

Clinical examination should include visual assessment using magnification and illumination, vitality testing, periodontal probing, radiographs, and sometimes CBCT. Dis-assembly and investigation may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Using a microscope with transillumination may highlight a crack, and a dye such as methylene blue may help if it is not visibly stained.

Cracked cusp detection

A plastic bite-stick such a Tooth Slooth® II (Professional Results Inc.) or FracFinder™ (Denbur Inc.) can be used to apply force to each individual cusp and may highlight the presence of a cuspal fracture. The patient can also be asked to bite on a cotton-wool roll to flex a crack in the tooth, and on-release pain may be elicited. Many of these teeth are vital or reversibly pulpitic and will react to cold stimuli such as EndoFrost (Roeko).

Periodontal pocketing

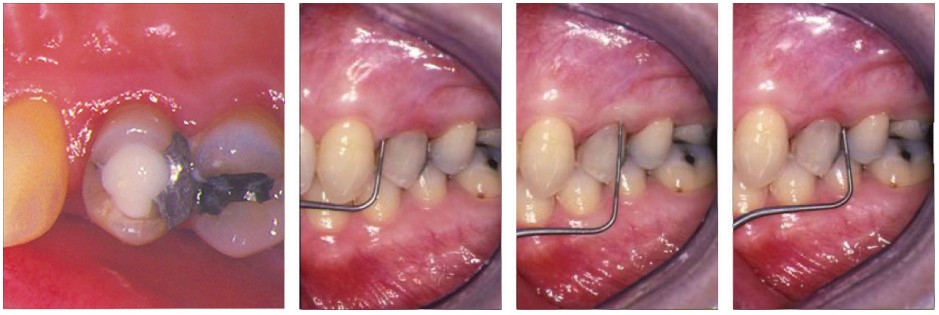

Periodontal probing can reveal the presence of a root fracture; a deep narrow pocket could be indicative of a root fracture but could also be a sinus tract. Deep narrow pocketing on both sides of a tooth, however, is almost pathognomonic (Figure 1).

Radiographs

It is unlikely that a crack will be seen on a radiograph unless the X-ray beam has passed through the line of the crack. Osseous changes can be detected around the root of the root. The classic presentation of a “J”-shaped radiolucency that wraps around the apex of the tooth can be indicative of a crack but can also be the produced by a chronic abscess. There may be crestal or furcal bone loss or widening of the periodontal ligament.

CBCT

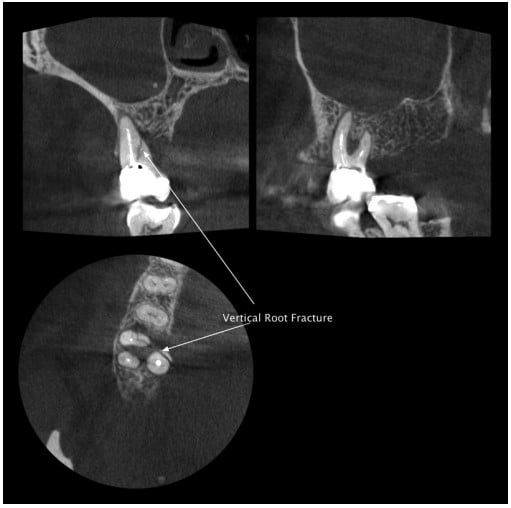

Cone beam computed tomography is invaluable for assessment of horizontal or oblique cracks in anterior teeth that have suffered trauma. A CBCT image gives information on the angle and location of a crack that cannot be gleaned from a radiograph. In posterior teeth, CBCT is generally not a reliable method for detecting cracks. There are often large restorations in teeth that are cracked, and these can cause artifacts on the image, obscuring detail. If a crack is significant, it may be visible; but to avoid confusion with artifacts, it is a good idea to look for any sign of radiolucency in the adjacent osseous detail. If there is a change in the periodontal ligament on both sides of a root, then it is likely that a crack is present (Figure 2).

Investigation

Carefully removing a restoration and assessing the extent of a crack with magnification and illumination will allow the operator to make a decision on whether a tooth is restorable and the likely prognosis for survival following root canal treatment (Figure 3).

Prognosis

There are several factors that could affect prognosis:

- Multiple cracks

- Terminal teeth

- Preoperative periodontal pocketing

- Cracks across the pulp floor or down a root canal

Terminal teeth have greater occlusal stress placed on them as they are nearer to the axis of the TMJ, and those that act as abutments for fixed or removable prosthetics may also be placed under increased stress. Post-crown restorations, for example, have a lower survival rate when used as abutments. Teeth that are bounded by others appear to have some protection offered by the teeth either side (Tan, et al., 2006).

Preoperative periodontal pocketing may indicate the presence of a crack. Sometimes this can be seen using the operating microscope by gently retracting the gingival with a flat plastic and looking directly at the root surface.

Cracks that extend across the pulp floor or down a root canal are associated with a lower survival rate in root-filled teeth (Sim, et al., 2016), and so could determine that the tooth would be better extracted and replaced (Figure 4).

Restoration post-endodontics

To reduce the risk of fracture after root canal treatment, molar teeth that are heavily restored with loss of marginal ridges should be restored with a cusp coverage restoration. When there is significant loss of tooth volume, a full-coverage restoration may be required. In anterior teeth restored with post crowns, a ferrule of at least 1.5 mm – 2.0 mm will provide an increased bracing effect and reduce the risk of fracture (Sorensen and Engelman, 1990).

Find out more

To see how these steps are applied, visit https://youtu.be/RErqBWyGyXI, or search YouTube for john rhodes endo identification diagnosis and management of cracks. The author is happy to answer questions directly via YouTube @john rhodes endo.

References

- Sim IG, Lim TS, Krishnaswamy G, Chen NN. Decision Making for Retention of Endodontically Treated Posterior Cracked Teeth: A 5-year Follow-up Study. J Endod. 2016;42(2):225-229.

- Sorensen JA, Engelman MJ. Ferrule design and fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;(63)5:529-536.

- Tan L, Chen NN, Poon CY, Wong HB. Survival of root filled cracked teeth in a tertiary institution. Int Endod J. 2006; 39(11):886-889.

John Rhodes, BDS(Lond), FDS RCS(Ed), MSc, MFGDP(UK), MRD RCS(Ed), is a specialist in endodontics, the author of textbooks and numerous papers, and owner of The Endodontic Practice Poole and Dorchester. He lectures and teaches on endodontics nationally.

John Rhodes, BDS(Lond), FDS RCS(Ed), MSc, MFGDP(UK), MRD RCS(Ed), is a specialist in endodontics, the author of textbooks and numerous papers, and owner of The Endodontic Practice Poole and Dorchester. He lectures and teaches on endodontics nationally.